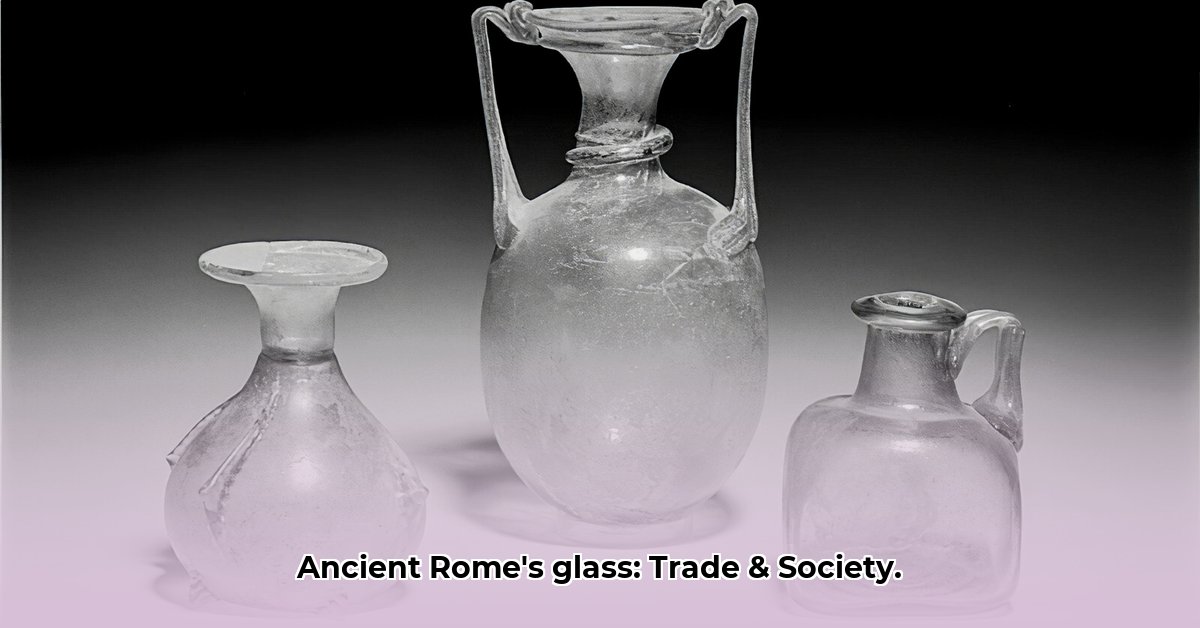

Ever wondered how a material as seemingly simple as glass could weave itself into the very fabric of an empire’s technological, economic, and social development? In ancient Rome, glass transcended its early status as a rare, imported luxury, evolving into a fundamental element of daily life and a testament to Roman ingenuity. This article delves into the remarkable journey of glass in the Roman world, exploring its transformative impact—from groundbreaking innovations in production to its pervasive influence on trade, cultural exchange, and societal stratification. We uncover how a fragile material became an enduring symbol of Roman prosperity and artistic ambition, leaving a legacy that continues to shape modern glassmaking.

The Genesis of Roman Glassmaking: From Imitation to Innovation

Before the Roman era, glassmaking traditions flourished in ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt as early as the fifteenth century BCE, primarily through labor-intensive techniques like core-forming and casting. Core-forming involved building glass around a removable mud and straw core, typically for small, thick-walled unguent or scent containers. Casting, which required pouring molten glass into molds, was used for vessels and decorative objects. These methods, while producing beautiful results, were slow and limited the scale of production, making glass an exclusive commodity.

However, the Roman glass industry experienced a profound revolution with the invention of glassblowing in the Syro-Palestinian region around the 1st century BCE. This ingenious technique allowed artisans to inflate molten glass by blowing air through a hollow iron rod, creating diverse, lightweight, and elegantly designed vessels with unprecedented speed and efficiency. As Seneca marveled in his Epistulae Morales, the glassblower could, “by his breath alone, fashion glass into numerous shapes which could scarcely be accomplished by the most skilful hand.” Need more details? Discover more here. This innovation drastically reduced production costs and significantly expanded the range of forms glassware could take, making it far more accessible and paving the way for mass production.

The burgeoning Roman Empire, with its vast trade networks and growing economic power, became the perfect crucible for glassblowing to flourish, attracting skilled artisans and fostering a rapid ascent of the industry.

The Science Behind the Splendor: Raw Materials and Production

Roman glass production relied on the precise application of heat to fuse primary ingredients, a process distinct from the subsequent “glass working” of finished items. The foundational components included:

- Silica (Former): The major component was sand (quartz), which naturally contained alumina (typically 2.5%, peaking around 3% in western Empire glasses) and up to 8% lime.

- Soda (Flux): To lower the melting point of silica, soda (sodium carbonate) was used exclusively. The primary source was natron, a naturally occurring salt found in dry lake beds, predominantly from Wadi El Natrun in Egypt.

- Lime (Stabilizer): Essential for preventing the glass from dissolving in water, lime typically entered the glass through calcareous particles in the beach sand itself rather than as a separate additive.

Roman glass also uniquely contained 1% to 2% chlorine, believed to originate from salt (NaCl) added to reduce melting temperature and viscosity, or as a contaminant in natron.

The raw glass was produced in large quantities in specialized furnaces, sometimes in structures capable of yielding several tonnes of glass in a single firing, such as the 8-tonne slab recovered from Bet She’arim. These large-scale “glassmaking” workshops, often located near fuel and raw material sources in the eastern Mediterranean, supplied chunks of raw glass to numerous “glassworking” sites across the empire. Unlike the intense heat required for primary glassmaking (around 1100 degrees Fahrenheit or 593 degrees Celsius), glassworking needed significantly lower temperatures (around 750 degrees Fahrenheit or 400 degrees Celsius), allowing workshops to proliferate in many locations, including Rome, Campania, and the Rhineland (e.g., Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium, modern Cologne).

The Romans also understood the value of recycled materials. As indicated by writers Statius and Martial, recycling broken glass was a vital part of the industry, with fragments rarely found in domestic sites of the period, suggesting widespread reuse. This practice was particularly extensive in the western empire, where broken glassware was melted back into raw glass.

A Spectrum of Colors: Pigmentation and Decolorization

The aesthetic appeal of Roman glass was significantly enhanced by its diverse color palette, achieved through the careful addition of metallic oxides and control of furnace conditions:

- ‘Aqua’: The natural pale blue-green hue of untreated glass, common in many early Roman vessels, resulted from the presence of Iron(II) oxide (FeO).

- Colorless: Highly prized, clear glass was produced by adding antimony or manganese oxide. These agents oxidized the naturally occurring Iron(II) oxide to Iron(III) oxide (Fe2O3), a much weaker yellow colorant, allowing the glass to appear colorless. The use of manganese as a decolorant was a Roman innovation first noted in the Imperial period, though antimony, a stronger decolorant, remained in use. Pliny the Elder, in his Natural History (36, 198), states that “the most highly valued glass is colourless and transparent, as closely as possible resembling rock crystal,” indicating a clear preference among the elite.

- Amber: Achieved under reducing conditions by iron–sulfur compounds (0.2%-1.4% sulfur and 0.3% iron).

- Purple: Created by adding approximately 3% manganese in an oxidizing environment.

- Blue and Green: Intensified with the addition of copper (2%-13%), derived from the recovery of oxide scale from scrap copper. Copper produced translucent blues that could darken to dense greens, further deepened by adding lead.

- Royal Blue to Navy: Produced by a mere 0.1% cobalt, yielding intense coloration.

- Powder Blue: Derived from Egyptian blue.

- Opaque Red to Brown (Pliny’s haematinum): A rare but valued color, achieved under strongly reducing conditions by precipitating cuprous oxide within the glass matrix, often with lead (1%-20%) to encourage precipitation and brilliance.

- White: Produced by adding 1%-10% antimony, which reacted with lime to precipitate calcium antimonite crystals, creating high opacity.

- Yellow: Resulted from the precipitation of lead pyroantimonate, typically using both antimony and lead. This color was often used in mosaic and polychrome pieces.

Over time, due to chemical reactions, the surface of some Roman glass artifacts developed a lustrous, rainbow-like effect known as iridescence, an unintended characteristic that is now highly admired.

Mastery of Form: Diverse Techniques and Artistic Expression

While glassblowing became dominant, Roman artisans continued to employ and refine a wide array of techniques to create masterpieces:

- Casting and Slumping: Though superseded by blowing for mass production, these older techniques remained in use for high-status items. Glass sheets, sometimes plain, multicolored, or formed of ‘mosaic’ pieces, were slumped over convex molds. This led to patterns like floral (millefiori), spiral, marbled, dappled, lace, and striped designs, often imitating natural stones like sardonyx. Pillar-moulded bowls, a common 1st-century find, often displayed marbled patterns.

- Mould-Blown Glass: Appearing in the second quarter of the 1st century AD, this technique combined blowing with carved molds, allowing for mass production of intricate designs, high-relief patterns, and decorative bosses. Examples include flasks shaped like sandals, wine barrels, or even animals.

- Cameo Glass: A luxury item involving layering different colors of glass and then carving away outer layers to create intricate, contrasting designs. The Portland Vase, made during the reign of Augustus (27 BCE – 14 CE) and depicting a Greek myth, stands as a prime example of this labor-intensive artistry.

- Cage Cups (Diatreta): Representing the zenith of Roman glass artistry in the 4th century CE, these were highly carved vessels where thick layers of glass were meticulously cut away to leave a delicate, lattice-like design or figures attached to the inner vessel only by small, hidden glass bridges. The Lycurgus Cup, currently in the British Museum, is a famous example of green and red dichroic glass depicting the myth of Lycurgus. The Cologne cage cup is another renowned piece.

- Gold Sandwich Glass: A technique where a layer of gold leaf, often with a design or portrait, was fixed between two fused layers of glass. Most survivals are decorative roundels from cup bottoms, used to mark graves in the Roman Catacombs, primarily Christian, from the 3rd to 5th centuries. This technique also gave rise to gold tesserae for mosaics.

- Other Techniques: Engraving, enameling, and applying hot glass trails or small pieces onto vessels further enhanced decorative possibilities. Glass could also receive pre-printed designs, though surviving examples are rare.

Beyond the Vessel: Glass in Roman Daily Life and Public Spaces

Roman glass permeated nearly every aspect of daily life, extending far beyond simple drinking vessels:

- Household Items: Cups, bowls, plates, and bottles became common for storing and serving food and drinks. Small alabastra and unguentaria held oils, perfumes, and cosmetics.

- Personal Adornment: Glass beads, cameos, and intaglios were incorporated into jewelry, often imitating prized semi-precious stones like emerald, sapphire, and amethyst. Roman mirrors, made with colorless glass backed by wax, plaster, or metal, provided reflective surfaces.

- Architecture: From the Augustan period onwards, shards and rods of glass were used in mosaics. By the 1st century AD, small, purpose-made glass tiles (tesserae) became standard in mosaics, especially in shades of yellow, blue, or green, used under fountains or as highlights. Window glass first appeared around the same time. Early panes were rough-cast into wooden frames, while later, from the 3rd century, the more efficient muff process (flattening a blown cylinder) was used. Roman window glass primarily provided insulation and security rather than perfect transparency.

- Miscellaneous Uses: Glass was also used for game pieces, small sculptures, and, in powdered form, even as a medicine and toothpaste. Some vessels held religious offerings or cremated remains, buried as grave goods. Romans sometimes believed glass had protective or magical properties, leading to inscriptions or charms on certain vessels.

The Imperial Network: Trade, Economy, and Social Status

The Roman glass industry was a vibrant economic force. Major production hubs flourished in cities like Alexandria, Sidon, and, later, centers like Cologne and Aquileia, benefiting from proximity to raw materials or key trade routes. These specialized workshops created numerous jobs and stimulated regional economies.

The distribution of Roman glass products relied on the vast network of Roman land and sea trade routes. Not only did finished goods