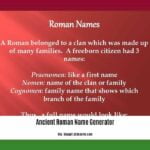

Ever found yourself pondering a possible connection to the grandeur of the Roman Empire? The notion of tracing your family tree back to such an ancient and powerful civilization is undeniably compelling. For the ancient Romans, names were far more than simple labels; they were intricate systems, evolving over centuries, packed with vital clues about an individual’s identity, their family lineage, social standing, and even personal characteristics. This comprehensive guide will decode the essential components of Roman nomenclature—the praenomen (first name), nomen (family name), cognomen (nickname or additional surname), filiation, and tribus—highlighting how these conventions varied for men, women, and enslaved or freed individuals. Discover how thoroughly understanding these naming practices can help you unlock fascinating historical insights and potentially trace compelling connections to the Roman past.

The Anatomy of a Roman Name: A System of Identity and Lineage

Roman names were complex, reflecting the dynamic nature of their society. Far from arbitrary designations, these names served as concise summaries of social position, familial bonds, and individual traits. The evolution of Roman onomastics provides invaluable insights into their societal and cultural transformations.

The Core: The Tripartite Naming System for Men

While early Romans might have used just a single name, the burgeoning complexity of a growing society necessitated a more robust system. By the Middle Republic, most Roman citizens (men) adhered to a tripartite naming convention, often referred to as the tria nomina. This structure offered a detailed glimpse into their identity and served as a defining characteristic of Roman citizenship, though its consistent application varied over time.

-

The Praenomen (Personal Name):

This functioned as the personal, or given, name, akin to a modern first name. However, the pool of common praenomina was remarkably limited, with choices such as Marcus, Gaius, Lucius, and Publius being exceptionally popular. Families frequently maintained a tradition of passing down a select few of these names across generations. This practice not only emphasized familial continuity but also distinguished the customs of one gens from another. Patrician gentes, in particular, often limited their use of praenomina more strictly than plebeians, reinforcing their exclusive social status. Numerical names, such as Quintus (fifth) or Sextus (sixth), were also commonly assigned, often reflecting the birth order among sons.- Abbreviation: Praenomina were almost always abbreviated in writing (e.g., M. for Marcus, C. for Gaius, L. for Lucius, P. for Publius). This practice speaks to their commonality and the Romans’ efficiency in record-keeping.

-

The Nomen Gentilicium (Family Name):

This was the crucial hereditary surname, identifying an individual’s affiliation with a specific gens (clan or extended family). These names almost invariably concluded with the Latin adjectival suffix “-ius” (e.g., Julius, Cornelius, Aemilius, Fabius). Possessing a nomen was akin to publicly displaying one’s family lineage, signaling a clear group identity within Roman society. The gens itself could function almost as a “state within a state,” observing its own rites and laws, making the nomen a powerful indicator of collective heritage and political alliance. -

The Cognomen (Additional Surname/Nickname):

Initially, the cognomen served as a personal nickname, often derived from a distinctive personal attribute, a geographical origin, an occupation, or a notable achievement. For instance, “Crassus” denoted “fat,” “Rufus” indicated “red-haired,” “Agrippa” (possibly “born feet first”), or “Africanus” commemorating military success in Africa. These names could even hint at a person’s profession (e.g., Cincinnatus, “curly-haired”) or a family’s historical narrative.- Evolution: While originally informal and personal, cognomina frequently became hereditary, particularly in large gentes, where they served to identify distinct branches or stirpes. For example, the powerful gens Cornelia included branches like the Cornelii Scipiones. By the Imperial period, the cognomen became the principal distinguishing element of the Roman name, as praenomina became less distinctive.

Beyond the Tripartite: Filiation, Tribus, and Agnomen

Beyond the tria nomina, a Roman citizen’s full name could include even more layers of identification, especially in formal records:

-

Filiation (Paternal and Maternal Lineage):

One of the oldest elements, the filiation identified a person by their father’s (and sometimes mother’s or grandfather’s) praenomen. This was crucial for distinguishing individuals with the same praenomen and nomen. For example, “M. f.” meant “Marci filius” (son of Marcus). This tradition, often abbreviated, provided a clear patronymic link, such as “P. Cornelius Scipio A. f.” (Publius Cornelius Scipio, son of Aulus). Inscriptions could extend to include grandfathers (n. for nepos) and even great-grandfathers. Interestingly, maternal filiation (gnatus following the mother’s name) was also sometimes included, particularly in families of Etruscan origin, where women held a comparatively higher social status. -

Tribus (Voting Tribe):

From the early Republic, Roman citizens were enrolled in one of the voting tribes (tribus) that constituted the comitia tributa, or tribal assembly. Membership in a tribe remained an important part of Roman citizenship, and the name of the tribe (e.g., Palatina, Cornelia, Collina) came to be incorporated into a citizen’s full nomenclature, usually abbreviated and placed after the filiation but before the cognomen. There were eventually 35 tribes, primarily geographic. -

Agnomen (Honorary or Adoptive Suffix):

On occasion, a Roman man would acquire an additional name, known as the agnomen. This was typically an honorary title commemorating a momentous achievement or a significant event. A prime example is Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus, who earned his agnomen “Africanus” following his decisive victories against Hannibal in Africa during the Second Punic War. This type of name functioned as a public badge of honor, permanently affixed to their identity. Another form of agnomen arose from adoption, where the original nomen of the adopted individual would be modified with a suffix like “-ianus” (e.g., Publius Cornelius Scipio Aemilianus, adopted from the Aemilia gens).

Naming Across Roman Society: Variations and Transformations

Roman naming customs were not static; they adapted over time in response to societal shifts, social mobility, and increasing imperial reach.

-

Women’s Naming Conventions: A Simpler, Yet Telling System

Roman women’s naming conventions presented a simpler, yet distinct, structure, reflecting their societal roles. Generally, Roman women did not possess a praenomen in formal use by the late Republic. Instead, they were primarily identified by the feminine form of their father’s nomen. Thus, a daughter born into the Julius gens would be known simply as Julia. If a family had multiple daughters, they were further distinguished by descriptive cognomina or numerical suffixes (e.g., Servilia Major for the elder, Servilia Minor for the younger, or Servilia Prima, Secunda, Tertia for multiple sisters).

It is noteworthy that women typically retained their birth names even after marriage, emphasizing their connection to their paternal gens. However, sometimes their husband’s cognomen was added to subtly indicate their married status, linking them to his social standing (e.g., Caecilia Metella, indicating a Caecilia married into the Metellus family). -

Names of Slaves and Freedmen: A Reflection of Social Standing

An individual’s name also clearly delineated their position within the Roman social hierarchy. Enslaved persons, occupying the lowest rung, usually bore a single name, frequently of Greek origin (e.g., Tiro, Hermes, Felix). This singular designation served as a clear indicator of their unfree status, fundamentally distinguishing them from the broader Roman populace. The widespread use of Greek names among the enslaved population often reflected their common geographic origins or specific skills.

Upon receiving freedom through manumission, a freedman underwent a profound transformation in their naming convention, a clear marker of their new social standing. Now free, the individual typically adopted the praenomen and nomen of their former master. Their original enslaved name often became their new cognomen, symbolizing their transition into Roman society and their ongoing, though altered, connection to their former owner through the patronage system. For instance, an enslaved person named Tiro, freed by Marcus Tullius Cicero, would become Marcus Tullius Tiro. -

Polyonymy and Later Imperial Names:

In the later Empire, Roman aristocratic names became increasingly complex, a phenomenon known as polyonymy. Individuals might adopt multiple nomina and cognomina from both paternal and maternal ancestors, sometimes resulting in names with dozens of elements. This practice reflected a desire to showcase an illustrious pedigree, inherit property, or solidify prestigious social connections.

The Constitutio Antoniniana of AD 212, which granted Roman citizenship to virtually all free men within the Empire, had a profound impact. As most newly enfranchised citizens took the praenomen and nomen of the emperor Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (Caracalla), the defining function of these names diminished. Consequently, cognomina (often including non-Latin original names) became the most important distinguishing element. By the 6th century, as Roman institutions faded, the complex system largely reverted to single names, often derived from former cognomina, which then influenced the development of modern European naming practices.

Deciphering the Past: A Genealogist’s Guide to Roman Names

Understanding ancient Roman names is akin to possessing a secret decoder ring for Roman history. These names provide invaluable clues about familial connections, social standing, geographical origins, and even personal characteristics. How can you begin to leverage this powerful information in your own historical investigations?

The Power of Roman Onomastics

Roman names, when meticulously analyzed, reveal a wealth of information:

- Familial Connections: The nomen immediately identifies the gens, indicating a broad family network. Hereditary cognomina further narrow this down to specific branches (stirpes).

- Social Standing: The presence or absence of certain naming elements, and their complexity, often correlated with an individual’s status. For instance, the tria nomina was a mark of citizenship, while single names primarily indicated enslaved status.

- Geographical Origins: Many cognomina were derived from places, indicating where an individual or a family branch originated (e.g., “Sabinus” from the Sabine region, “Norbanus” from Norba). Slave names often hinted at their country of origin (e.g., Greek names).

- Personal Attributes or Achievements: Cognomina often directly described physical traits (e.g., “Rufus” for red hair, “Calvus” for baldness), occupations, or significant life events, offering a unique glimpse into character or history.

- Historical Events: Agnomina and specific cognomina ex virtute (e.g., Africanus, Germanicus, Asiaticus, Parthicus) directly commemorate military triumphs or political achievements, linking individuals to major historical turning points.

Practical Steps for Genealogical Research

Successfully deciphering ancient Roman family connections requires meticulous attention and a structured approach. Here’s how to start using this information yourself:

| Roman Name Element/Type | Significance for Genealogy | Examples & Clues |

|---|---|---|

| Praenomen | Indicates family tradition; limited pool. Can suggest patrician or plebeian status based on usage patterns. | Marcus, Gaius, Lucius, Publius (common). Unusual names in patrician families could signal revival of older traditions. |

| Nomen Gentilicium | The primary identifier of the gens or clan. Essential for placing an individual within a major Roman family. | Julius, Cornelius, Aemilius. Look for the “-ius” ending. |

| Cognomen | Originally a personal nickname, often became hereditary, distinguishing branches (stirpes) within a gens. Reveals personal traits, origins, or achievements. | “Crassus” (fat), “Rufus” (red-haired), “Sabinus” (from Sabine region), “Coriolanus” (captured Corioli). |

| Agnomen | An additional, often honorary, surname commemorating a specific achievement or adoption. Crucial for identifying renowned individuals or family line transitions. | Scipio Africanus (victory in Africa), Aemilianus (adopted from Aemilia gens). |

| Filiation | Directly links an individual to their father (and sometimes grandfather/mother). Essential for differentiating individuals with identical praenomen and nomen. | “M. f.” (son of Marcus), “L. n.” (grandson of Lucius). Can reveal a family’s Etruscan roots if maternal filiation is present. |

| Tribus | Indicates the voting tribe. While less frequent in casual records, its presence can confirm citizenship and provide a geographical or political context for enrollment. | Examples: Palatina, Cornelia. Usually abbreviated. |

| Women’s Names | Typically the feminized form of the father’s nomen. Numerical or descriptive cognomina distinguish sisters. Marriage rarely changed the nomen, but a husband’s cognomen might be added. | Julia, Cornelia, Servilia Major. Consistency in the nomen indicates paternal lineage. |

| Slave Names | Usually a single name, often Greek. Can offer clues about the enslaved person’s origin or even perceived character (e.g., positive names like Felix for “lucky”). | Felix, Tiro, Hermes. |

| Freedmen’s Names | Adopted praenomen and nomen of former master, with the original slave name as their cognomen. A clear indicator of manumission and patronage ties. | Marcus Tullius Tiro (freed by M. Tullius Cicero). Look for the “-ianus” suffix on a cognomen after AD 212. |

| Polyonymy | The practice of having multiple nomina and cognomina from both paternal and maternal lines; common in the later Empire, indicating extensive aristocratic connections. | Indicates a highly prestigious or politically connected individual, often with a complex inherited pedigree. |

Critical Pitfalls in Tracing Ancient Roman Genealogy

The allure of Roman roots is strong, but before envisioning yourself as a direct descendant of a Roman senator, it is crucial to address some common critical mistakes in tracing ancient Roman genealogy that often lead to dead ends or inaccurate conclusions.

-

Expecting Detailed Records for the Average Person:

Let’s be realistic: uncovering detailed birth certificates, comprehensive census data, or marriage records stretching back two millennia is simply not feasible for the vast majority of people. For most of us, such specific, personal Roman records ceased to exist long ago. The relentless march of time, devastating wars, widespread natural disasters, and the inherent fragility of ancient documents have taken their inevitable toll. This does not mean all hope of a general connection is lost, but it certainly necessitates a significant adjustment of expectations regarding direct, documented lineages. -

Ignoring the Timeline Realities of Surviving Records:

For reliable genealogical work, the practical starting point for accessible and verifiable primary records generally begins from the 1500s onward in Europe. Prior to this, records become increasingly scarce, fragmented, and difficult to interpret accurately for direct linear tracing. While ancient Rome remains a captivating subject for study and broader historical connection, for the practical purpose of tracing a direct lineage, concentrating on more recent centuries offers a significantly higher probability of success. -

Over-Reliance on Unverified Online Family Trees:

The proliferation of online family trees and genealogical databases can be highly tempting, offering seemingly effortless ways to fill in ancestral gaps. However, a significant caveat applies: these digital trees are frequently rife with inaccuracies, speculative leaps, and unverified claims. It is paramount to always, without exception, verify any information encountered online with primary historical sources, such as original church records, land deeds, or authenticated historical documents. Consider these online trees merely as potential clues or starting points for your own rigorous research, not as irrefutable gospel. The success rate for verifying online data without cross-referencing is notably low, often leading to “phantom ancestors.” -

Dismissing the Value of Genetic Genealogy (DNA):

While traditional paper trails may not extend into antiquity for most, direct-to-consumer DNA testing can provide valuable, albeit broad, insights into deep ancestral origins. While these tests will not typically name specific Roman ancestors, they can effectively reveal ancestral origins in geographical regions that were once under profound Roman influence (e.g., Italy, Hispania, Gaul, Britannia, North Africa, the Levant). Think of DNA analysis as uncovering a broader, ancient geographical footprint of your lineage, rather than pinpointing individual names. This represents a powerful, statistically informed approach to understanding deep ancestry and identifying potential regions where Roman connections might exist. -

Underestimating the Impact of Historical Context and Record Loss:

History is rarely a clean or linear narrative. Understanding the profound impact of major historical events—such as large-scale migrations (e.g., Völkerwanderung), devastating wars (e.g., fall of Western Roman Empire), widespread plagues (e.g., Antonine Plague), and the collapse of administrative systems—is crucial. These factors significantly affected both record-keeping practices and the movement and mixing of populations across continents over millennia. Neglecting these broader historical contexts is one of the most critical mistakes in tracing ancient Roman genealogy, as it can lead to unrealistic expectations or misinterpretations of available evidence. Countless historical documents frequently succumbed to the ravages of war, fire, or natural disasters, creating insurmountable gaps in the record that no amount of research can bridge. -

Neglecting Female Ancestors and Maternal Lines:

It is an easy error to focus predominantly on the male line when tracing ancestry, perhaps due to traditionally more accessible male-centric records (e.g., property inheritance, military service). However, female ancestors are equally, if not more, vital to a complete genealogical picture. The maternal line often survives differently in DNA (e.g., mitochondrial DNA) and provides unique insights into population movements. Never overlook the importance of your female ancestors; they hold just as many crucial clues to your past and are indispensable for constructing robust, accurate lineages.

Tools for Success: Navigating the Complexities

To significantly minimize inaccuracies and enhance the reliability of your genealogical research, consider implementing the following strategic approaches:

| Strategy | Description |

|---|---|

- Stuck on ‘Heads of Ancient Rome’ NYT? CAPITA is the Answer (Here’s Why!) - August 16, 2025

- Unearth ancient rome roads: Empire’s power and modern highway’s origin - August 15, 2025

- Discover geography of ancient Rome: Empire’s secrets revealed (2024 insights) - August 15, 2025