Ever wondered what women in ancient Rome wore? Forget the toga – that iconic garment was primarily reserved for men! We’re diving deep into the fascinating world of Roman women’s fashion, from their essential daily attire to the extravagant ensembles they donned to signify their status and wealth. Clothing in ancient Rome was far more than mere covering; it was a sophisticated visual language, a “secret code” that instantly communicated a woman’s social standing, marital status, and adherence to societal norms. Join us as we explore key pieces like the foundational *tunica*, the dignified *stola* (a clear badge of a married woman), and the versatile *palla* (the quintessential outer wrap). We’ll uncover the rich array of fabrics, the opulent accessories, and how these sartorial choices evolved over centuries, offering an invaluable peek into the intricate lives of women across all strata of ancient Roman society. For further insights, see this information on [**ancient Roman attire**](https://www.lolaapp.com/ancient-roman-attire-women/).

The Threads of Identity: Understanding Ancient Roman Women’s Attire

Step back in time to ancient Rome, a civilization renowned for its grandeur, power, and intricate social structure. Within this complex tableau, women’s fashion played an exceptionally crucial role. It wasn’t simply about aesthetics; what a Roman woman wore profoundly influenced how she was perceived, instantly signaling her place within the elaborate social hierarchy, her marital status, and even her moral character. Understanding what did women wear in ancient Rome is to understand a visual dialogue, a silent yet powerful discourse that defined identity and adherence to societal expectations.

The Foundational Layer: Undergarments and the Tunica

At the core of every Roman woman’s wardrobe lay practical and comfortable undergarments. Like men, Roman women wore a type of loincloth called a subligar or subligaculum. For breast support, they often used a strophium or mamillare, a strip of cloth wrapped around the chest, serving as an early form of a bra.

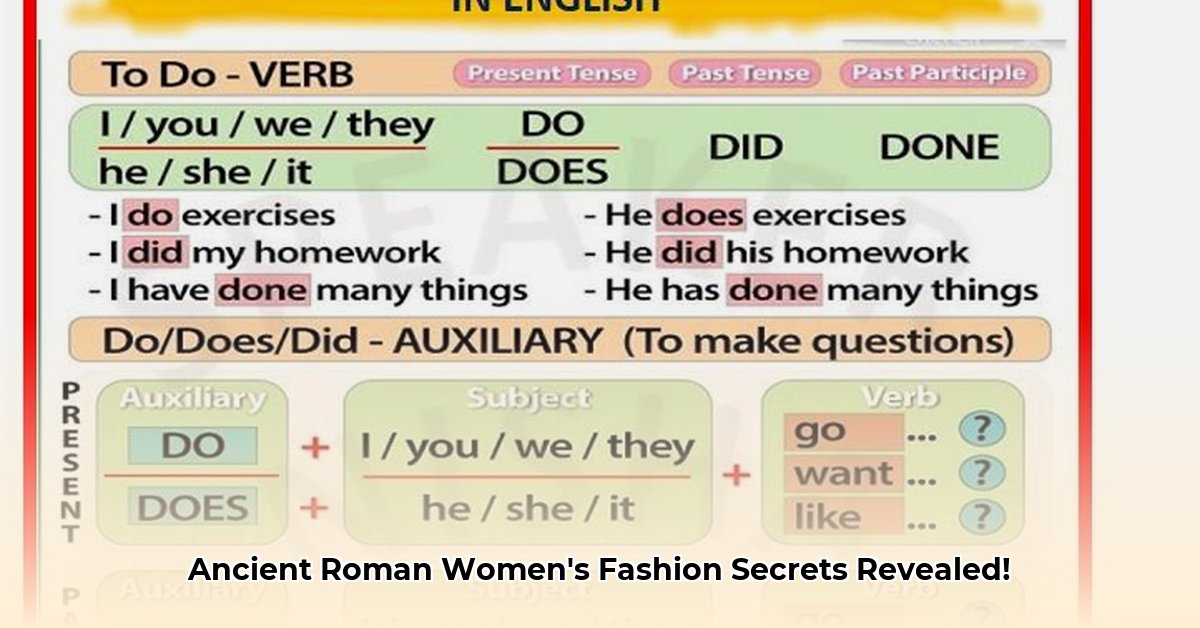

Over these basics, the tunica was the indispensable garment, serving as the universal foundation for all social classes. Imagine a simple, loose-fitting slip dress made from two rectangular pieces of fabric, pinned or sewn at the shoulders and down the arms, then belted at the waist. While broadly similar in design, the tunica‘s material and embellishments were powerful indicators of status:

- Materials and Status: Poorer women, including slaves (who were often provided only one rough wool tunica per year, as advised by Cato the Elder), wore plain, undyed wool. Wealthier women, however, would choose tunicae made from finer linen, cotton imported from distant lands, or even delicate silk, showcasing their affluence. The width of the cloth determined sleeve length; wider fabric allowed for longer sleeves.

- Styles and Draping: Two primary styles of tunica were common:

- Chiton style: Similar to its Greek counterpart, this tunica was sewn almost entirely down the sides, fastened along the arms and shoulders with a series of brooches or pins. Its versatility allowed for belting under the breasts, around the waist, or on the hips, creating varied silhouettes.

- Peplos style: This was a sleeveless variation, also sewn down the sides but featuring a distinct top fold that created a draped effect over the back and front. It was fastened at each shoulder with a brooch.

- Daily Life: The tunica provided comfort and freedom of movement for daily activities, from domestic chores for commoners to leisurely pursuits for the elite. Its simplicity belied its importance as the first layer of self-presentation.

The Mark of a Matron: The Stola

Perhaps the most symbolic garment for a Roman woman was the stola, worn over the tunica. This long, sleeveless dress, suspended from the shoulders by straps, was the unequivocal badge of a matrona—a freeborn Roman woman who was legally married. Its significance transcended mere fashion, communicating respectability, dignity, and adherence to Roman ideals of marriage, family, and virtue.

- Symbolic Power: Only free, married women were permitted to wear the stola. Its absence, or the wearing of a toga (which became almost exclusively a male garment by the mid-Republic), could signify a woman as divorced due to infamy, or worse, a prostitute. The stola thus provided immediate visual clarity regarding a woman’s social and moral standing within Roman society.

- Fabric and Embellishment as Status: While the basic form of the stola remained consistent, its material and decoration loudly proclaimed the wearer’s wealth. Wealthy women favored costly imported silks, finely woven linens, or soft wools, often adorned with intricate embroidery or even precious metals woven into the fabric. A particularly esteemed feature was the instita, a visible ornamental hem, often dyed purple, that further elevated the wearer’s status, akin to the purple stripes on an elite man’s toga.

- Evolution and Controversy: The stola was not static; it evolved with changing fashions and cultural influences, sometimes incorporating elements from Greek attire. As Roman society progressed into the Empire, more flattering and less restrictive styles became popular, leading some women to “flout the law,” as noted by contemporary observers like the Christian author Tertullian. He famously critiqued women who appeared in public “without stolas,” equating this disregard for traditional dress with moral laxity. The satirist Juvenal also attacked women who abandoned traditional attire for more revealing or athletic wear, reflecting societal anxiety over shifting gender norms. While the matronal stola had no fixed color, the stola of the revered Vestal Virgins was presumably white.

The Versatile Wrap: The Palla

Completing the ensemble, the palla was a large, rectangular shawl or wrap worn over the tunica and stola. Its precursor in the early Republic was a simpler square cloak called a ricinium. The palla, however, was a more elegant garment, typically draped from the left shoulder, falling under the right arm, and often covering the head.

- Functionality and Style: The palla served multiple purposes: providing warmth, offering an additional layer of modesty, and adding a striking element of style. Its versatility allowed for numerous draping styles, some of which became fashionable trends in different periods, potentially with regional variations. For respectable women, particularly matrons and Vestal Virgins, its back fold could be used to modestly cover the head when out in public or during religious ceremonies.

- Status Display: As with other garments, the material and color of the palla were clear indicators of the wearer’s wealth and social standing. Affluent women would parade vibrant pallas made of luxurious silks or finely dyed wools, often with rich embellishments, while those of lesser means wore simpler, coarser versions.

Beyond the Garments: Accessories, Grooming, and Their Significance

Roman women’s fashion extended far beyond the main garments, encompassing elaborate hairstyles, exquisite jewelry, and practical footwear, all meticulously chosen to enhance their appearance and telegraph their societal position.

- Hairstyles and Headwear: Hairstyles were an incredibly expressive part of a Roman woman’s look. Initially simple in the Republic, often consisting of a chignon or rolled plaits, styles became increasingly elaborate during the Empire, heavily influenced by empresses who dictated trends for intricate curls, waves, and towering coiffures. Such complex styles often required the assistance of personal hairdressers, making them a preserve of the wealthy elite. These coiffures were adorned with jeweled hairpins made of precious metals, bone, or ivory, and delicate hairnets of gold or silver. Wigs and hairpieces were also common, allowing for greater stylistic flexibility.

- Jewelry and Adornments: Jewelry was a primary means of displaying wealth and taste. Necklaces, bracelets, earrings, rings, and even toe rings, crafted from gold, silver, and precious gems (emeralds, pearls, sapphires), were highly coveted. Commoners might wear simpler adornments, perhaps made of glass beads or bronze fibulae (brooches, similar to safety pins, used to fasten garments). The quantity and quality of a woman’s jewelry not only signified her personal wealth but also her family’s standing. Protective amulets like the bulla, sometimes worn by adult women but more commonly by children, were also part of their adornment, warding off evil.

- Footwear: Footwear, though often hidden by long garments, was essential. Sandals, typically made of leather, were ubiquitous for comfort. Wealthier women boasted more elaborate sandals, sometimes adorned with jewels or intricate straps. Softer slippers were worn indoors, while practical leather boots might be used for travel or colder weather. The craftsmanship and embellishment of footwear further underscored economic standing.

- Makeup and Fragrance: Roman women also used cosmetics to enhance their appearance. White lead was used as a foundation to achieve a pale complexion, while red ochre or plant dyes provided blush for cheeks and lips. Kohl was used to darken eyelashes and eyebrows, and perfumes, made from imported oils and floral essences, were popular among the elite.

Fabric, Color, and Social Stratification: A Visual Language

The choice of fabric and color in Roman women’s clothing was perhaps the most direct and potent visual cue of social status, rigorously enforcing class distinctions.

- Materials: While basic wool and linen were accessible to most, the wealthy had exclusive access to luxurious materials. Fine, lightweight wools, high-quality linen, and especially imported silk from the East were symbols of opulence. Cotton, though less common than wool or linen, also made its way into the wardrobes of the affluent. The texture, weight, and beading details of these fabrics were easily recognizable indicators of their superior quality and incredible expense.

- Dyes and Colors: The vibrancy and rarity of dyes directly correlated with wealth. Muted, natural, or common dyes like madder (red) were typical for the lower classes. However, vibrant hues, especially deep purples, were highly coveted. Tyrian purple, extracted from murex snails, was famously costly and associated with royalty and extreme affluence. A garment dyed with this color was an unmistakable declaration of immense wealth. Other bright colors, such as saffron yellow or indigo blue, also signified luxury.

- Clothing Laws and Protests: So ostentatious did elite female clothing become in the late Republic that anti-opulence laws were enacted. However, these sumptuary laws were often flouted and even repealed after women took to the streets in protest, showcasing their collective power and desire for self-expression through fashion.

Fashion as Social Commentary and Control: The Policing of Dress

The way Roman women dressed was a constant subject of public scrutiny, criticism, and even legislative control, reflecting deeply ingrained societal expectations and gender roles. As Tertullian’s writings attest, women who deviated from the prescribed modest attire, particularly the stola, were seen as challenging established norms and even inviting moral condemnation.

Juvenal, another prominent satirist, vividly portrays the societal discomfort with women who dared to adopt “unfeminine” attire, such as exercise gear or armor for training. He lambasted women who “loathed their own gender,” engaging in physical sports, questioning their modesty and adherence to traditional roles. This policing of women’s clothing highlights how deeply intertwined fashion was with social order, moral character, and the very definition of womanhood in ancient Rome. The strictures on dress for enslaved women, limiting them to simple tunics devoid of elaborate styles or colors, further illustrate how clothing maintained and reinforced the rigid social divides.

Cultural Influences and Enduring Legacy

Roman women’s fashion was not static but a dynamic tapestry woven with threads from various cultures. Through conquests and trade, Roman attire absorbed significant influences from Greece and the East, introducing new fabric types, cuts, and styles. The elegant draping characteristic of Hellenistic fashion, for instance, noticeably shaped Roman silhouettes, leading to a unique blend that became distinctively Roman over time.

Even the practicalities of garment care offer insights into Roman life. The fullonica, an ancient dry cleaner, highlights the importance of textile maintenance. In the absence of modern soap, ancient Romans famously used urine as a cleansing agent, a fascinating example of their resourceful approach to keeping clothes clean and presentable.

The clothing styles of ancient Roman women laid profound groundwork for future fashion trends. Elements of the stola, with its flowing lines and structured drape, and the palla, with its versatile wrapping, can be seen echoed in various styles throughout history, up to modern times. Examining artifacts, artwork, and historical accounts reveals the enduring contribution of Roman women’s fashion to broader discussions of gender, social hierarchies, and cultural exchanges, underscoring clothing’s essential role in personal identity and societal expression across millennia.

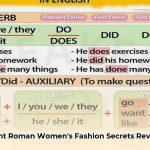

Here’s an overview of the key elements of Roman women’s fashion:

| Garment/Accessory | Primary Materials | Key Significance | Social Marker | Evolution/Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subligar/Mamillare | Linen, wool | Basic undergarments for modesty and support. | Worn by all classes. | Functional, largely unchanged. |

| Tunica | Wool, linen, cotton, silk for elite | Foundational garment; daily wear. | Quality and embellishment denoted wealth. Rough wool for poor/slaves, fine linen/silk for wealthy. | Styles like chiton and peplos offered versatility. |

| Stola | Wool, linen, silk | Badge of a married, respectable free Roman woman (matrona). | Exclusive to married freeborn women; its absence, or wearing of a toga, indicated infamy. | Evolved in draping, sleeve design, hemlines; subject to social policing and criticism for deviations. |

| Palla | Wool, silk, fine fabrics | Versatile outer wrap; modesty, warmth, style. | Material and elaborate draping indicated wealth and status. | Draping styles varied and became trendy; used to cover head by matrons and Vestal Virgins. |

| Hairstyles | Natural hair, wigs, hairpieces | Signified status, often elaborate. | Complex styles (requiring hairdressers) indicated wealth. | Simpler in Republic, became highly ornate in Empire, influenced by Empresses. |

| Hairpins | Bone, ivory, precious metals | Secured elaborate hairstyles. | Material indicated wealth. | From functional to highly decorative. |

| Jewelry | Gold, silver, precious stones, glass beads | Display of wealth, social standing, personal taste; sometimes protective (e.g., bulla). | Quality and quantity directly correlated with wealth. | From simple brooches (fibulae) to intricate necklaces and rings. |

| Footwear | Leather, softer fabrics | Protection and comfort; status symbol for elaborate versions. | Embellished sandals/boots for wealthy, plain for poor. | Practical designs for daily wear, more decorative for special occasions. |

| Fabrics/Dyes | Raw materials: wool, linen, silk. Dyes: madder, indigo, Tyrian purple. | Primary visual indicator of class/wealth. | Tyrian purple exclusive to extreme wealth; commoners wore muted colors. | Increased availability of exotic fabrics (silk, cotton) with expanding trade routes. |

In essence, delving into what did women wear in ancient Rome reveals a complex system where clothing transcended mere utility. It served as a powerful tool for social communication, a reflection of individual identity, and a constant barometer of the changing socio-cultural landscape of one of history’s most fascinating civilizations. The story of Roman women’s fashion is, truly, the story of their lives, intricately woven into the very fabric of society.