The Renaissance, a period spanning roughly from the 14th to the 17th century, is often heralded as a profound rebirth of culture and learning in Europe. At its very core lay a transformative reimagining of art, literature, and philosophy, fueled by a fervent return to the ideals of classical antiquity. But precisely how deeply did ancient Greek and Roman sculpture, architecture, and philosophical thought infuse and redefine the artistic landscape of this groundbreaking era? This comprehensive exploration delves into the multifaceted ways classical masterpieces served not merely as inspiration, but as catalysts for an artistic revolution that laid the foundations for the modern world. For more, see this page on Ancient Greek Art.

The Resurgence of the Human Form: Sculpture’s Profound Influence

Centuries after their creation, the rediscovery and celebration of ancient Greek and Roman sculptures profoundly captivated Renaissance artists. These unearthed masterpieces, found in various states of preservation—some during routine excavations for new buildings, others by chance in fields—offered a stark contrast to the more stylized and symbolic figures prevalent in medieval art. They showcased an unparalleled understanding of human anatomy, idealized proportions, and dynamic, naturalistic poses.

Consider the profound impact of iconic pieces such as the Apollo Belvedere, the Laocoon Group, and the Belvedere Torso. The Apollo Belvedere, a breathtaking second-century Roman copy of a Greek bronze original, epitomized classical serenity and physical perfection. Its graceful contrapposto stance and idealized male form became a powerful benchmark for Renaissance artists striving for anatomical accuracy and balanced composition. Michelangelo, a towering figure of the High Renaissance, reportedly admired the Belvedere Torso so immensely that he referred to it as his “teacher,” drawing inspiration from its powerful, albeit fragmented, portrayal of internal struggle and muscular tension for figures in the Sistine Chapel.

The discovery of the Laocoon Group in 1506 near Nero’s Golden House was a monumental event in Rome, witnessed by Michelangelo himself, who was deeply moved by its dramatic portrayal of agony and muscular exertion. This Roman copy of a Greek Hellenistic sculpture depicted the Trojan priest Laocoon and his sons in a desperate struggle against sea serpents. Unlike the calm perfection of the Apollo Belvedere, the Laocoon presented intense emotion and dynamic conflict, influencing artists to explore the dramatic narrative and emotional depth in their own works, pushing beyond mere idealism to capture raw human experience.

Artists like Donatello, with his revolutionary bronze David, directly echoed the triumphant ideal of an ancient Greek athlete, signifying a decisive departure from previous artistic norms towards a renewed focus on the human body as a subject worthy of study and celebration. This direct engagement with ancient forms provided not just models, but a conceptual framework for representing the human figure with unprecedented realism and emotional resonance.

Humanism: The Intellectual Underpinning of Artistic Rebirth

The Renaissance was not merely an artistic movement; it was driven by Humanism, a powerful intellectual current that fundamentally shifted Europe’s worldview. Humanism emphasized the inherent value, dignity, and potential of human beings. Fueled by the systematic recovery and rigorous study of classical Greek and Roman literature, philosophy, and history, humanists championed reason, individualism, and civic virtue over purely theological dogma.

This profound philosophical shift directly encouraged artists to focus on the human form, celebrating its inherent beauty, strength, and intellect as a reflection of divine creation and human capability. Michelangelo’s David stands as a quintessential example, embodying classical ideals of physical perfection intertwined with intellectual prowess and civic strength. This period witnessed a significant move from solely divine focus to appreciating human capabilities and achievements, evident in the meticulously detailed anatomies and expressive faces within Renaissance artworks. The focus on individual character in portraiture, a practice firmly rooted in ancient Roman traditions, also experienced a significant resurgence, highlighting individual identity and personal achievement.

Humanism’s influence extended to artistic techniques as well. The re-evaluation of ancient texts on optics and geometry, such as those by Euclid and Ptolemy, spurred Renaissance artists to pioneer innovations like linear perspective. This mathematical system allowed artists to create the illusion of depth and three-dimensionality on a flat surface, mirroring the Humanist fascination with rational order and the tangible, observable world. Figures like Leon Battista Alberti, a true uomo universale, not only conceptualized these principles but applied them directly to both painting and architecture, advocating for the rational design of space.

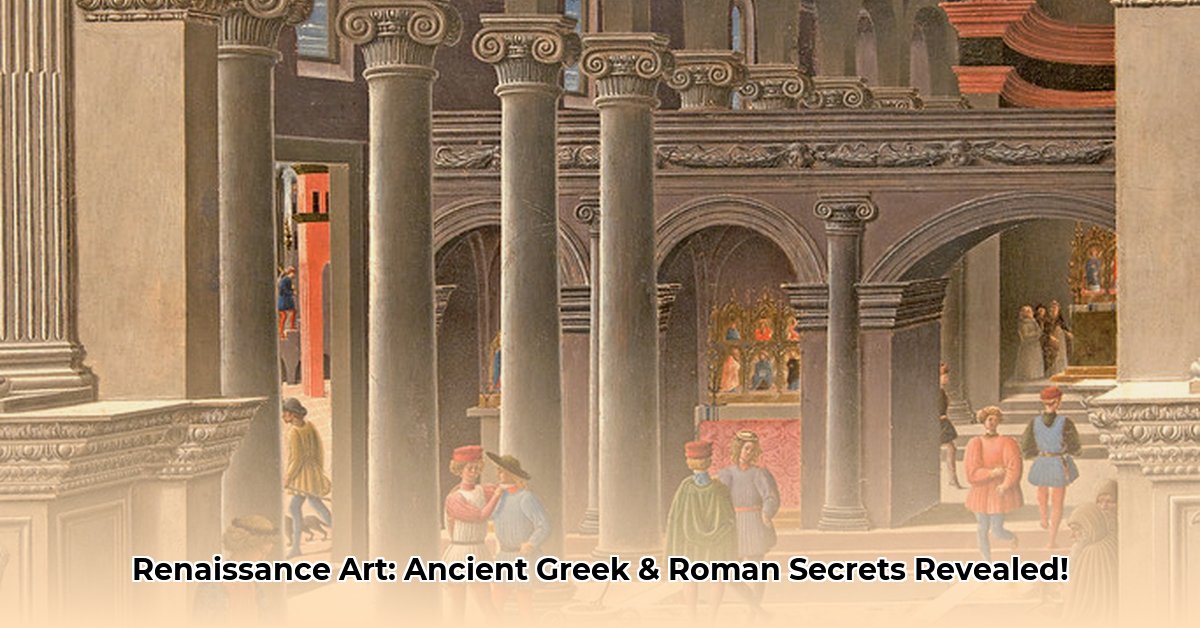

Architectural Echoes: Classical Principles Reborn

The architectural principles of ancient Greece and Rome experienced a profound rebirth during the Renaissance. Architects meticulously poured over ancient Roman ruins and scholarly texts like Vitruvius’ De architectura (On Architecture), a first-century BC treatise that detailed classical building methods and aesthetic principles. This intense study allowed them to rediscover and judiciously adapt ancient construction techniques and aesthetic principles, creating a distinct style that celebrated both history and innovation.

Structures like Filippo Brunelleschi’s groundbreaking Dome for the Florence Cathedral and Donato Bramante’s designs for St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome stand as powerful testaments to the enduring influence of classical design. Brunelleschi’s ingenious double-shell structure and revolutionary herringbone brickwork, achieved without traditional scaffolding, demonstrated remarkable construction skills and a definitive departure from medieval building norms. Architects meticulously incorporated classical elements such as columns (Doric, Ionic, Corinthian orders), arches, barrel vaults, domes, and pediments, striving for the ultimate harmony, balance, and mathematical purity in their creations, often guided by precise ratios mirroring the classical pursuit of ideal forms and proportions.

Later architects, such as Andrea Palladio, further refined these classical principles in the High Renaissance, creating designs characterized by their elegance, balance, and logical clarity. His villas and palaces in the Veneto region, often featuring classical porticos and symmetrical layouts, became models for countless buildings across Europe and later in the Americas, profoundly influencing movements like Neoclassicism. This re-emphasis on order, symmetry, and human-centered scale fundamentally reshaped the European urban landscape, moving away from the soaring, often asymmetrical, forms of Gothic architecture towards a more grounded and rationally ordered aesthetic.

Subject Matter and Allegory: Recapturing Ancient Narratives

Classical mythology and historical events found new life and prominence in Renaissance art. Artists drew profound inspiration from these rich narratives, infusing their works with layered symbolism and intricate allegory. Sandro Botticelli’s Birth of Venus, painted in the mid-1480s, is a prime example, drawing heavily on classical mythology to explore universal themes of beauty, love, and creation. The depiction of a pagan goddess on a monumental scale, a subject unthinkable in earlier periods, illustrates the humanist shift towards incorporating and celebrating pre-Christian narratives.

Beyond mythology, historical subjects from ancient Rome and Greece, such as battles, philosophical debates, and heroic deeds, also provided rich material. These narratives allowed artists to explore themes of virtue, courage, and civic responsibility, aligning with the Humanist ideals of active engagement in the world. The portrayal of these subjects often sought to capture not just the event, but the underlying emotions and psychological states of the figures involved, a hallmark of the Renaissance’s deeper exploration of the human condition.

Transformation, Not Just Replication: A New Artistic Language

While the profound impact of classical antiquity is undeniable, Renaissance artists did much more than simply copy past masterworks. They actively transformed classical themes and techniques, adapting them to reflect the unique values and sensibilities of their own time and culture. This was not a mere revival but a dynamic synthesis, where classical forms were imbued with new meaning, often integrated with Christian theology, and explored through innovative artistic methods.

The development of oil painting techniques, for instance, allowed for greater depth, richer color, and more subtle transitions of light and shadow (sfumato, as mastered by Leonardo da Vinci) and dramatic contrasts (chiaroscuro). These advancements enabled artists to achieve greater realism and emotional intensity than was possible with earlier mediums, transcending the capabilities of their ancient predecessors. The Renaissance became a period of unparalleled artistic and intellectual ferment, building upon the established foundations of classical art to develop entirely new styles, innovative techniques like linear perspective, and fresh interpretations of form and narrative. This creative synthesis is what truly defines the ‘rebirth’ aspect of the period.

| Aspect | Ancient Greek & Roman Influence | Renaissance Transformation |

|---|---|---|

| Sculpture | Emphasis on idealism, anatomical accuracy, contrapposto | Greater emotional expression, exploration of individual character, dynamic poses, combined with a newfound focus on realism and psychological depth. |

| Painting | Principles of balanced composition, implied perspective (through form) | Development of linear perspective, sfumato, and chiaroscuro; more dynamic compositions, atmospheric depth, and vibrant color palettes with oil paints. |

| Architecture | Use of columns, arches, domes, pediments, mathematical ratios | Integration of classical elements with innovative engineering techniques (e.g., Brunelleschi’s dome), human-centered scale, and new building types. |

| Subject Matter | Classical mythology, historical narratives, realistic portraiture | Christian themes intertwined with classical motifs, nuanced allegorical interpretations, secular subjects, and the celebration of individual achievement. |

| Philosophical Basis | Emphasis on reason, civic duty, human potential | Humanism’s reinterpretation of classical thought, leading to a focus on human agency, individual achievement, and a more secular worldview within a Christian context. |

The Power Behind the Brush: The Impact of Patronage

The Renaissance, a period synonymous with artistic brilliance, owes much of its splendor to its elaborate and robust patronage system. Elite families, powerful civic bodies, and the omnipresent Church significantly fueled this era, commissioning everything from intricate paintings to monumental architectural designs and sculptures. Their influence was multifaceted, shaping not only the artistic output but also defining the cultural values and public image of the time.

Wealthy individuals and institutions invested heavily in art for various reasons: personal satisfaction, the desire for lasting commemoration, and profound religious piety were common drivers. Many influential figures, drawing inspiration directly from ancient Roman benefactors, viewed art as a powerful means to establish an enduring legacy. These commissions allowed patrons to dictate the portrayal of subjects, effectively presenting themselves in a light that emphasized sophistication, education, and affluence. For instance, ambitious merchants, eager for social recognition, commissioned portraits that mirrored the refined style of the established elite. Religious institutions, conversely, sought art for spiritual solace, the promise of eternal salvation, and to vividly showcase their devotion. Patrons often viewed art sponsorship as a civic duty, commissioning works that honored fellow city members or beautified public spaces.

The relationship between patrons and artists, though often a nuanced negotiation, was critical. Patrons frequently wielded considerable sway, dictating not only the cost of materials and the size of a piece but also its specific location and even the precise subject matter. In many instances, artists were perceived as skilled employees, expected to meticulously bring the patron’s vision to life. Formal contracts were common, meticulously outlining project specifics, agreed-upon fees, and stringent deadlines. However, some patrons, particularly those collaborating with already established and renowned artists, fostered a greater degree of artistic independence. The powerful Medici family in Florence, owing to their immense wealth and deep cultural appreciation, became pivotal patrons, fundamentally molding the city’s artistic identity for generations. Similarly, Pope Julius II’s extensive commissions in Rome profoundly impacted the artistic landscape, setting new standards for grandeur and spiritual expression while providing artists like Michelangelo access to newly discovered ancient artifacts.

The Renaissance patronage system was, therefore, a symbiotic relationship. While patrons provided essential financial support and often shaped the artistic direction, artists, in turn, sculpted the cultural landscape and produced timeless masterpieces that transcended their initial purpose. This dynamic interplay between wealth, power, devotion, and sheer artistic ingenuity unequivocally defines the art of the Renaissance, demonstrating why a collaborative approach, even with constraints, can lead to unparalleled creative output.

| Aspect | Patron’s Influence | Artist’s Influence |

|---|---|---|

| Subject Matter | Dictated themes, specific figures, and core narratives, often for prestige or devotion. | Interpreted themes with individual style, bringing personal insights and emotional depth. |

| Materials/Scale | Set budget constraints and specified preferred materials (e.g., marble, bronze, fresco). | Selected techniques and mediums, optimizing for desired effect within constraints. |

| Location | Determined the final placement and visibility of the artwork (public or private display). | Adapted designs to suit specific architectural or spatial contexts, enhancing impact. |

| Timeline | Established deadlines and overall project duration, often with penalties for delays. | Managed time and resources efficiently to meet expectations and maintain quality, sometimes pushing boundaries. |

| Overall Vision | Provided overarching goals and objectives for the artwork, often tied to personal status or legacy. | Infused artwork with personal artistic vision, technical mastery, and creative innovation, often surpassing initial expectations. |

The Lasting Echoes: Shaping Future Civilizations

The Renaissance was more than a period of stylistic shifts; it was an era that fundamentally redefined the relationship between humanity, art, and the past. By looking back to ancient Greece and Rome, Renaissance artists, architects, and thinkers did not merely re-enact history; they reimagined it. They took the principles of classical perfection, human-centered design, and rational inquiry, then infused them with new techniques, profound spiritual insights, and a burgeoning sense of individualism.

The influences derived from ancient Greek and Roman sculpture, architecture, and philosophy laid the groundwork for subsequent artistic movements, from the Baroque’s dramatic dynamism to the Neoclassical emphasis on order and civic virtue. The legacy of this period continues to resonate, reminding us that true innovation often springs from a deep understanding and creative adaptation of the past. The Renaissance stands as a testament to the enduring power of classical ideals and the boundless potential that arises when tradition meets unbridled creativity, forever shaping the way we perceive beauty, human potential, and the very act of creation itself.