The Roman Empire, a civilization renowned for its military might and administrative prowess, owes much of its enduring success to an often-overlooked yet profoundly innovative achievement: its vast network of roads. These were not merely pathways but sophisticated arteries that facilitated unprecedented military mobility, spurred economic prosperity, and fostered cultural unity across a sprawling domain. This article delves into the profound significance of Roman roads, breaking down their innovative construction, exploring their multifaceted impact, and examining their lasting legacy that continues to resonate in the modern world. Embark on a journey through time to discover how these remarkable feats of engineering underpinned the greatest empire of the ancient world.

The Strategic Imperative: Rome’s Interconnected Lifeline

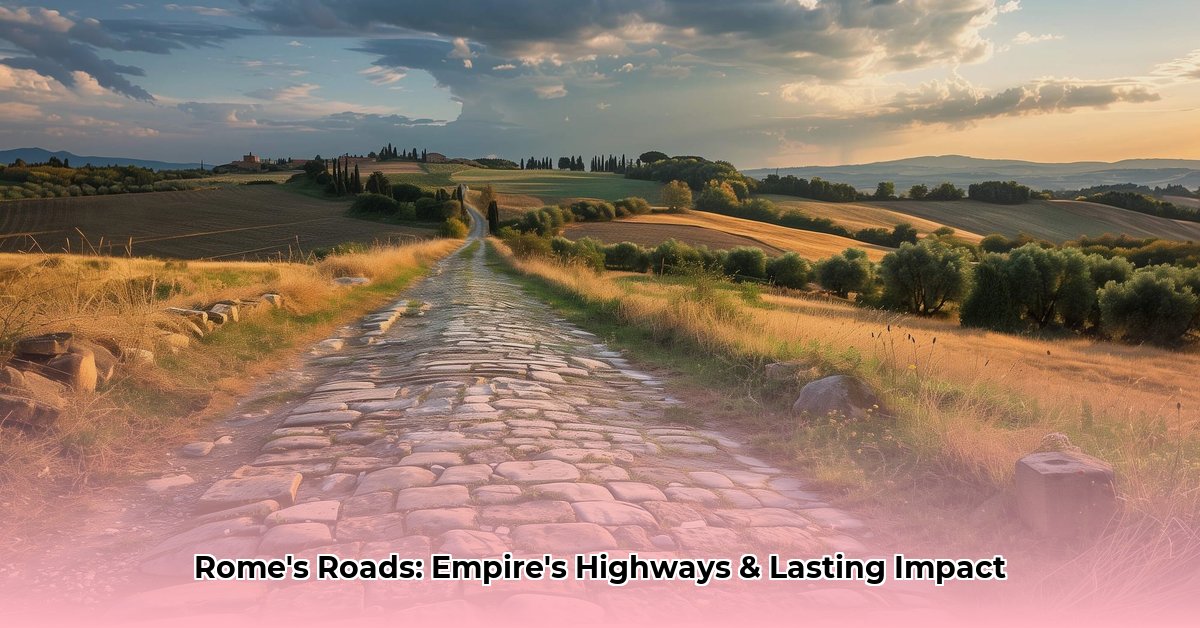

The Roman road system was the indispensable infrastructure that propelled the Roman state’s expansion and sustained its long-term stability. Initiated around 312 BCE with the monumental Via Appia (Appian Way), this ambitious project evolved into an intricate network covering over 400,000 kilometers (approximately 250,000 miles) at the peak of the empire’s development. Of this immense length, more than 80,500 kilometers (50,000 miles) were masterfully stone-paved, a testament to Roman engineering ingenuity.

These meticulously planned highways served as strategic arteries, radiating from the capital to connect major cities, military bases, and even isolated provinces. The network reached from Britain in the northwest, across the European continent, to the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in the east, and from the Danube River south to Spain and North Africa. This comprehensive system dramatically accelerated Rome’s expansion, consolidation, and administrative efficiency, making it a visible indicator of Rome’s pervasive power and a critical tool in unifying a vast melting pot of cultures, races, and institutions.

Engineering an Enduring Masterpiece: Construction Methods and Durability

The extraordinary longevity and effectiveness of Roman roads were no accident; they were the direct result of meticulous planning, advanced surveying techniques, and a sophisticated layered construction approach that set a precedent for infrastructure development for millennia. Roman land surveyors, known as agrimensores, utilized precision instruments like the groma (a device for establishing true lines and right angles) and the dioptra to plot the most direct routes possible between two points, even if they were not visible to each other. This often meant audaciously cutting through hillsides, draining marshes, clearing forests, and constructing impressive bridges and viaducts over valleys and rivers.

The construction itself followed a rigorous multi-layered design, ensuring unparalleled durability and functionality. A typical Roman road featured:

- Fossa (Excavation): The process began with digging a trench, or fossa, down to bedrock or the firmest ground available. The depth of this excavation varied significantly based on the terrain.

- Rudus (Foundation): The bottom layer, or statumen, comprised large, flat stones set in mortar or rough gravel, providing a stable, solid foundation. In marshy areas, wooden piles or rafted foundations were employed.

- Nucleus (Base Layer): Above the statumen, a layer of finer gravel or crushed stones mixed with lime-based mortar, known as the nucleus, was compacted. This prepared a strong, impermeable base.

- Summum Dorsum (Surface Layer): The final surface layer, or pavimentum, consisted of tightly fitted polygonal blocks of volcanic rock (basalt or silice), dressed stone blocks, or large paving stones. For less prestigious sections or rural roads, a durable gravel surface mixed with lime was used.

A crucial design element was the convex shape of the road surface, known as camber, which sloped slightly from the center down to the curb. This ingenious feature ensured that rainwater would efficiently run off into parallel ditches or drainage canals along the sides, significantly reducing erosion and preventing water damage to the roadbed. Pedestrian paths, typically 1 to 3 meters wide and made of packed gravel, often flanked the main road, separated by substantial curb stones. Milestones (miliarium), circular columns inscribed with the distance to Rome and maintenance records, were regularly placed along routes, aiding navigation and administration.

Roman engineers demonstrated remarkable adaptability, modifying their techniques and material choices based on local availability and environmental conditions. Their preference for engineering solutions over circumvention led to the construction of awe-inspiring structures:

- Bridges and Viaducts (Pontes): From the modest single-vaulted Ponte di Mele to the colossal 700-meter viaduct over the Carapelle River, these structures enabled straight routes across water and valleys. Many, like the Milvian Bridge in Rome (109 BCE) and the bridge over the Tagus at Alcantara (106 BCE), are still standing, a testament to their robust construction using durable blocks of stone and early forms of Roman concrete.

- Tunnels: Essential for avoiding lengthy detours, tunnels were excavated often from both ends (counter-excavation), requiring impressive geometric precision. Notable examples from the 1st century BCE include Cumaea (1,000 m), Cripta Neapolitano (705 m), and Grotta di Seiano (780 m). While labor-intensive (sometimes only 30 cm of progress per day), these tunnels were critical in maintaining the desired straightness of routes.

The Dual Power: Military Might and Economic Lifeline

The primary motivation behind Rome’s extensive road network was undeniably military strategy. These roads enabled Roman legions to traverse immense distances with unprecedented speed, moving as quickly as 20 miles a day. This unparalleled mobility was crucial for:

- Rapid Deployment: Swiftly dispatching troops to suppress rebellions, reinforce frontier outposts, and respond to external threats across vast territories, from Britain to Dacia and beyond the Euphrates.

- Logistical Superiority: Ensuring the timely supply of provisions and equipment to armies in the field via wheeled vehicles, lessening the need for large, costly garrison units at every remote location. Key routes like the Via Egnatia in the Balkans and the Via Claudia Augusta in the Alps were vital for these military objectives, proving decisive in numerous campaigns.

Beyond military logistics, Roman roads revolutionized commerce and fostered unprecedented economic integration. These transit paths enabled the efficient transportation of diverse goods across the empire, facilitating a seamless flow of commodities: from grain sourced in Egypt and olive oil from Spain, to exotic spices from the East and manufactured goods from artisan centers. This dramatically boosted economic activity, leading to the proliferation of market towns and tabernae (roadside hostels) along main routes.

The cursus publicus, the efficient Roman state postal system founded by Augustus, relied heavily on these roads. Messages and official dispatches were carried with remarkable speed by couriers on horseback or in light chariots (cisium). A network of way stations:

- Mutationes (Changing Stations): Located approximately every 20-30 kilometers (12-19 miles), these provided fresh horses and repair services (wheelwrights, cartwrights, veterinarians), allowing couriers to cover up to 80 kilometers (50 miles) in a single day.

- Mansiones (Rest Stations): Situated roughly every 25-30 kilometers (16-19 miles), these more lavish state-run hotels offered full accommodation for official travelers, complete with lodgings for people and animals, places to eat, bathe, and even hire services. Non-official travelers could use private cauponae (inns), though these were often seen as disreputable.

Furthermore, these routes facilitated profound cultural exchange, weaving together the empire’s diverse populations by allowing new ideas, technologies, and beliefs—including the rapid spread of Christianity—to disseminate freely across provinces, fostering a sense of shared Roman identity.

Navigating the Network: Legal Frameworks and Road Classifications

The Roman legal system played a fundamental role in the administration, construction, and maintenance of its extensive road network. Roman law defined the right to use a road as a servitus, or liability, thereby establishing clear claims for public passage. The ius eundi granted the right to use a footpath across private land, while the ius agendi allowed for a carriage track. A via combined both, with specific width requirements (a minimum of 8 Roman feet, or roughly 2.37 meters, increasing to 12 feet in rural areas for public roads). Notably, laws like the Lex Julia Municipalis restricted commercial vehicles in urban areas during the day, highlighting sophisticated traffic management.

The financing and upkeep of roads were a significant responsibility. Initially overseen by prestigious censors, this duty later devolved to various curatores viarum (commissioners of roads) and local magistrates, with contributions sometimes levied from neighboring landowners or even wealthy individuals like Julius Caesar.

Not all Roman roads shared the same status; they were categorized based on their purpose, funding, and construction methods:

- Viae Publicae (or Viae Militares/Consulares/Praetoriae): Public high roads, constructed and maintained at public expense, often named after the censor who commissioned them (e.g., Via Appia, Via Flaminia). These were the backbone of the military and administrative system.

- Viae Privatae (or Viae Rusticae/Glareae/Agrariae): Private or country roads, originally built by individuals or estates, with their soil vested in the owner, although they could be dedicated to public use. These connected public roads to specific properties.

- Viae Vicinales: Local roads connecting villages (vici) or districts, serving rural areas and linking to higher-tier roads. Their public or private status depended on initial funding.

- Viae Terrenae: Simple, unpaved leveled earthen tracks, typically the lowest tier of roads.

- Viae Glareatae: Earthen roads with a gravel surface or sub-surface.

- Viae Munitae: Built roads, paved with rectangular or polygonal blocks of stone, representing the highest construction standard.

This meticulously tiered system illustrates the Romans’ comprehensive and pragmatic approach to infrastructure development and governance.

An Undying Legacy: Roman Roads in the Modern World

Even today, the profound influence and enduring engineering brilliance of the Roman road system are palpable. Many modern routes across Europe and the Middle East precisely follow the paths of these ancient arteries, a testament to their optimally chosen alignments and strategic foresight. For example, Italy’s Strada Statale 7 closely traces the Via Appia, and major routes in Britain like the A1 and A5 align with Roman roads such as Dere Street and Watling Street. Some ancient bridges, like the Tre Ponti in modern Fàiti, Italy, still carry vehicular traffic today, showcasing a remarkable 2,000-year legacy of durability.

Roman engineering methods, particularly their layered construction, advanced surveying techniques, and sophisticated drainage principles, left an indelible mark on subsequent civilizations, from the Byzantine Empire to medieval Europe, and continue to inform modern road-building practices. Archaeological studies of Roman roads remain an invaluable source of information, providing deep insights into ancient Roman engineering prowess, urban planning, settlement patterns, and the daily lives of its citizens. The comprehensive network also allowed for the creation of ancient maps or itineraria, such as the famous Peutinger Table, which offers a unique cartographic insight into the Roman world’s interconnectedness.

The concept of a unified, centrally managed transportation network supporting commerce, administration, defense, and cultural exchange remains as crucial today as it was two millennia ago. Roman roads are not merely historical relics; they are powerful symbols of human ingenuity, resourcefulness, and the transformative power of infrastructure.

Actionable Insights for Today’s World

The enduring legacy of Roman roads offers valuable, actionable lessons across various fields, providing a blueprint for modern challenges in infrastructure, heritage, and urban planning.

| Stakeholders | Short-Term (0-1 Year) | Long-Term (3-5 Years) |

|---|---|---|

| Historians/Archaeologists | Launch targeted surveys utilizing ground-penetrating radar (GPR) and LiDAR along postulated Roman road corridors, especially in less-explored regions, to confirm and precisely map buried sections, bridges, or associated settlements. Prioritize the digital reconstruction of road segments based on archaeological findings and historical texts, collaborating with local communities to involve citizen scientists in initial surface surveys and data collection. | Establish a comprehensive, open-access GIS-based digital atlas of the entire Roman road network, integrating all known archaeological data, historical itineraries, and newly discovered segments. Implement predictive modeling techniques, leveraging environmental data and Roman settlement patterns, to identify high-probability areas for undiscovered road sections, tunnels, and waystations, leading to targeted excavations and preservation efforts. Develop international consortia for standardized data collection and sharing to create a globally comprehensive Roman road database. |

| Tourism Boards & Cultural Heritage | Develop immersive digital experiences (AR/VR apps) for key Roman road sites, allowing visitors to visualize the roads, their construction, and historical context, including the types of traffic and services. Create multi-lingual self-guided tours emphasizing the engineering marvels and the daily life facilitated by the roads. Partner with local businesses along existing Roman routes to develop themed accommodation, food, and craft offerings, creating direct economic benefits. | Institute a transnational “Roman Roads European Heritage Trail” program, connecting well-preserved sections across different countries with clear signage, interpretive centers, and educational programs. Organize annual international events (e.g., “Roman Road Weeks”) to promote cultural exchange, host academic conferences on shared heritage, and develop sustainable tourism models that balance visitor experience with site preservation. Seek UNESCO World Heritage status for significant, contiguous sections of the network, recognizing its global importance as a testament to ancient infrastructure. |

| Civil Engineers & Urban Planners | Conduct detailed material science analyses on surviving Roman road sections, focusing on aggregate composition, binder properties (early concrete), and layering techniques to understand their resilience to local climate and geological conditions. Research Roman drainage and cambering principles for application in contemporary urban design, particularly in areas prone to flash floods, integrating these ancient solutions into modern stormwater management systems. Explore the use of locally-sourced, low-carbon materials inspired by Roman building practices to reduce the environmental footprint of new road construction. | Develop and pilot next-generation, climate-resilient road designs that incorporate Roman principles of layered construction, superior drainage, and material adaptability, aiming for significantly extended service life and reduced maintenance cycles in an era of climate change. Implement urban planning strategies that prioritize the preservation and integration of ancient road remnants (where they coincide with modern routes) as green corridors or pedestrian zones, enhancing civic spaces and fostering historical awareness. Create training modules for contemporary engineers and planners based on “Mastering Ancient Roman Engineering Principles for Sustainable Infrastructure.” |

In essence, Roman roads were more than just infrastructure; they were a profound symbol of Roman resourcefulness, authority, and exceptional organizational skills. They underpinned military supremacy, encouraged economic expansion, facilitated cultural interaction, and left an enduring imprint on the world, a legacy that continues to instruct and inspire.