Have you ever stopped to truly appreciate the incredible engineering marvel that is your back? It’s more than just a support structure; it’s a dynamic, intricate system that allows you to move, bend, twist, and stand tall, all while housing and protecting the central communication highway of your body. Yet, for many, the profound complexity and vital functions of the spine remain a mystery until pain strikes.

This article invites you on an illuminating journey to unlock your back’s secrets. We will delve deep into the fascinating world of spine anatomy – exploring every bone, disc, ligament, and nerve that forms your remarkable backbone. More importantly, we’ll uncover the intricate physiology that dictates how these components work in perfect harmony, enabling every aspect of your movement and well-being. Prepare to gain a newfound appreciation for this unsung hero of your body and learn how to nurture its incredible capabilities.

The Magnificent Architecture of Your Backbone: A Deep Dive into Spine Anatomy

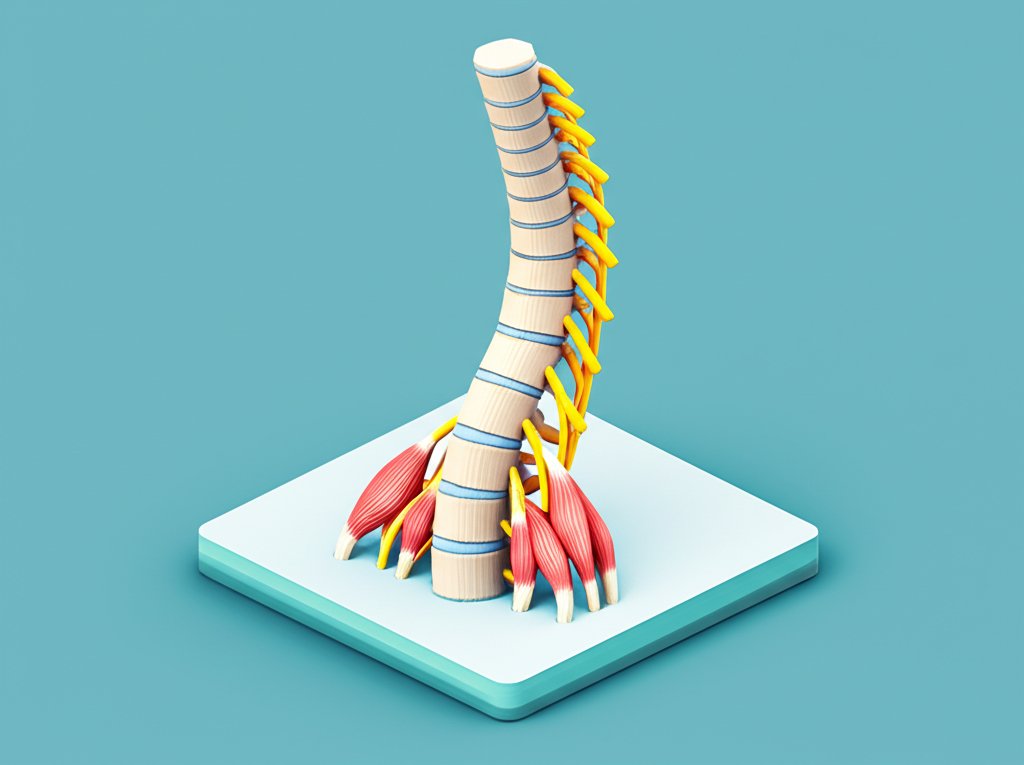

To truly understand the back, we must first dissect its structural marvels. The human backbone, or vertebral column, is a testament to nature’s genius, designed for both robust support and remarkable flexibility. It’s a complex stack of individual bones, cushioned by discs, bound by ligaments, and powered by muscles, all to protect the delicate spinal cord.

The Vertebral Column: Your Central Pillar

Your spine is comprised of 33 individual bones called vertebrae, stacked one upon another to form a flexible yet strong column. These vertebrae are categorized into five distinct regions, each with unique characteristics and functions:

- Cervical Spine (C1-C7): The Neck’s Agility

- These seven relatively small vertebrae form your neck, supporting your head and allowing for a wide range of motion. C1 (atlas) and C2 (axis) are specially designed for head rotation, enabling you to nod “yes” and shake “no.” Their delicate nature makes them vulnerable but also incredibly agile.

- Thoracic Spine (T1-T12): The Rib Cage Anchor

- The twelve thoracic vertebrae are larger and less mobile than the cervical ones, as they connect to your rib cage. This connection provides stability and protects vital organs in your chest, limiting rotation and flexion but offering crucial structural integrity.

- Lumbar Spine (L1-L5): The Powerhouse of the Lower Back

- These five largest and strongest vertebrae bear the brunt of your body weight and are crucial for lifting and bending. The lumbar region is highly susceptible to stress due to its weight-bearing role and flexibility, making it a common site for back pain.

- Sacrum (S1-S5, Fused): The Pelvic Foundation

- The five sacral vertebrae are fused into a single, triangular bone that forms the base of your spine and connects to your pelvis. This sturdy structure provides stability for your trunk and transmits weight to your hips and legs.

- Coccyx (3-5, Fused): The Tailbone

- Often called the tailbone, the coccyx is a small, fused bone at the very bottom of the spine, a vestigial remnant that can still cause pain if injured.

Intervertebral Discs: Shock Absorbers and Flexibility Facilitators

Between each movable vertebra (from C2 down to the sacrum) lies an intervertebral disc. These remarkable structures are essential for the physiology of spine movement and protection. Each disc consists of two main parts:

- Annulus Fibrosus: The tough, fibrous outer ring, similar to a radial tire, which provides strength and contains the inner jelly-like substance.

- Nucleus Pulposus: The soft, gelatinous center that acts as the primary shock absorber, distributing pressure evenly across the vertebrae.

These discs allow for slight movement between adjacent vertebrae, collectively contributing to the spine’s overall flexibility, and crucially, they cushion the impact of walking, running, and jumping, protecting the delicate bone structure.

Ligaments and Muscles: The Stabilizers and Movers of Your Back

Supporting the bony structure and discs are an intricate network of ligaments and muscles, vital for back stability and motion.

- Spinal Ligaments: Strong, fibrous bands connect vertebrae and discs, providing crucial stability and limiting excessive movement. Key ligaments include the anterior and posterior longitudinal ligaments (running the length of the spine) and the ligamentum flavum, which connects adjacent laminae.

- Back Muscles: These are some of the most powerful and complex muscles in the body, working synergistically to support the backbone, maintain posture, and facilitate movement.

- Superficial Muscles: Such as the latissimus dorsi and trapezius, primarily move the shoulders, arms, and head.

- Deep Intrinsic Muscles: These are the true workhorses of the back. Groups like the erector spinae (longissimus, iliocostalis, spinalis) run along the spine, responsible for extension (straightening the back) and lateral bending. Smaller, deeper muscles like the multifidus provide segment-specific stability and control. The core muscles (transversus abdominis, obliques) also play a critical role in supporting the lumbar spine.

The Spinal Cord and Nerves: Communication Highway

Nestled safely within the vertebral canal formed by the stacked vertebrae is the spinal cord, a thick bundle of nerves extending from the brainstem to the lumbar region. This is the body’s primary information superhighway, relaying sensory messages from the body to the brain and motor commands from the brain to the muscles.

- Spinal Nerves: At each vertebral level, pairs of spinal nerves branch off the spinal cord, exiting through small openings (foramina) between the vertebrae. These nerves then branch further, innervating every part of your body, controlling sensation, movement, and organ function. Damage or compression to these nerves, often due to issues with the surrounding anatomy, can lead to pain, numbness, or weakness throughout the body.

The Dynamic Functions of Your Back: Understanding Spine Physiology

Beyond its static structure, the back is a marvel of dynamic physiology, constantly adapting and performing a multitude of vital functions. Understanding how it works is key to appreciating its robustness and vulnerability.

Support and Posture: The Spine’s Primary Role

The most fundamental physiology of your backbone is to provide structural support for your upper body, neck, and head, and to transmit weight to your pelvis and lower limbs. This isn’t a simple straight column; the human spine has natural curves that are crucial for its function:

- Cervical Lordosis: An inward curve in the neck.

- Thoracic Kyphosis: An outward curve in the upper back.

- Lumbar Lordosis: An inward curve in the lower back.

These S-shaped curves act like a spring, distributing compressive forces more effectively than a straight column. They enhance the spine’s ability to absorb shock, maintain balance, and sustain loads without injury. The complex interplay of muscles around these curves constantly adjusts to keep your body aligned, ensuring optimal posture and reducing stress on individual vertebrae and discs.

Movement and Flexibility: A Symphony of Motion

The individual mobility afforded by each intervertebral disc and facet joint (small joints between vertebrae) accumulates to grant the entire backbone a remarkable range of motion. This physiology allows for:

- Flexion and Extension: Bending forward and backward.

- Lateral Bending: Bending to the side.

- Rotation: Twisting the trunk.

While the cervical spine offers the most flexibility, and the thoracic spine is the most rigid, the lumbar region provides substantial capacity for both flexion/extension and rotation required for daily activities. This fluid movement is a complex dance between muscular contraction, ligamentous tension, and the elasticity of the intervertebral discs.

Protection of the Nervous System: Your Body’s Lifeline

One of the most critical physiology functions of the back is the robust protection of the delicate spinal cord and the nerve roots branching from it. The bony arch of each vertebra forms a protective tunnel, shielding the nervous tissue from external trauma. This protection is paramount, as the spinal cord is the direct link between your brain and the rest of your body, responsible for:

- Transmitting motor signals from the brain to muscles, enabling voluntary movement.

- Relaying sensory signals (touch, temperature, pain, proprioception) from the body back to the brain.

- Mediating reflex actions without direct input from the brain, providing rapid responses to stimuli.

Any compromise to this protective function, such as a herniated disc pressing on a nerve or a fracture, can have widespread neurological consequences.

Biomechanics of Back Health: How Forces Act

Understanding the physiology of how forces act on your back is crucial for preventing injury. Simple activities like lifting, sitting, and standing exert significant pressure on your spine.

- Lifting: Improper lifting techniques (bending at the waist rather than the knees) can exponentially increase the load on your lumbar spine, straining muscles and discs.

- Sitting: Prolonged sitting, especially with poor posture, reduces the natural curves of the spine, places uneven pressure on discs, and can weaken core muscles, leading to chronic back pain.

- Standing: Standing without proper alignment can also strain the back muscles and ligaments over time.

The physiology of managing these forces involves engaging your core muscles, maintaining the natural curves of your backbone, and distributing weight evenly.

Common Challenges and Marvelous Adaptations of the Back

Despite its incredible design, the back is not immune to challenges. Its complex anatomy and dynamic physiology make it susceptible to various conditions, yet it also possesses remarkable resilience.

Understanding Back Pain: Anatomy Gone Awry

Back pain is a widespread issue, often stemming from disruptions in the intricate anatomy and physiology we’ve explored.

- Muscle Strains and Sprains: Overuse or sudden movements can pull muscles or stretch ligaments in the back, leading to acute pain.

- Herniated (Bulging) Discs: When the annulus fibrosus tears, the nucleus pulposus can bulge out, potentially pressing on nearby spinal nerves and causing radiating pain (like sciatica).

- Osteoarthritis: The “wear and tear” disease can affect the facet joints of the spine, causing stiffness and pain, especially in the lumbar and cervical regions.

- Spinal Stenosis: A narrowing of the spinal canal can compress the spinal cord or nerves, leading to pain, numbness, or weakness.

These conditions highlight how critical each component of the back anatomy is to overall health and function, and how even small issues can significantly impact physiology.

The Spine’s Incredible Healing Capacity

One of the most astonishing aspects of back physiology is its inherent capacity for healing and regeneration. While severe damage may require intervention, minor strains, sprains, and even some disc issues can often resolve with rest, proper movement, and time. The body’s natural repair mechanisms work to restore tissue integrity, rebuild bone, and reduce inflammation, a testament to the robust vitality of the backbone.

Nurturing Your Backbone: Practical Tips for a Healthy Spine

Given the vital role of your back in every aspect of your life, proactive care is not just beneficial—it’s essential. By understanding its anatomy and physiology, you can make informed choices to support its health.

Posture Perfect: Protecting Your Back in Daily Life

Maintaining good posture is perhaps the most impactful action you can take for your backbone.

- Standing: Keep your head level, shoulders relaxed, and stomach pulled in. Distribute your weight evenly on both feet. Avoid locking your knees.

- Sitting: Sit tall with your feet flat on the floor, knees at a 90-degree angle, and your back supported against the chair. Use a lumbar support pillow if needed to maintain the natural curve of your lower spine.

- Lifting: Always lift with your legs, not your back. Bend at your knees, keep the object close to your body, and straighten up slowly, engaging your core muscles.

Strengthening and Stretching: Essential for Spine Health

Regular exercise strengthens the muscles that support your spine and improves flexibility, both crucial for healthy back physiology.

- Core Strengthening: Exercises like planks, bird-dog, and pelvic tilts strengthen the abdominal and back muscles that act as a natural corset for your backbone.

- Stretching: Gentle stretches for the hamstrings, hip flexors, and back muscles can improve flexibility and reduce stiffness. Yoga and Pilates are excellent for enhancing overall spinal mobility and strength.

- Low-Impact Aerobics: Walking, swimming, and cycling improve circulation, strengthen supporting muscles, and maintain disc health without excessive impact on the spine.

Ergonomics at Work and Home: A Proactive Approach

Modify your environment to support your back’s natural anatomy and physiology.

- Workspace: Ensure your computer monitor is at eye level, your chair provides good lumbar support, and your keyboard and mouse are within easy reach. Take regular breaks to stand, stretch, and move.

- Sleep: Choose a mattress that supports the natural curves of your spine. Sleeping on your side with a pillow between your knees or on your back with a pillow under your knees can help maintain alignment.

- Footwear: Wear supportive shoes that cushion your feet and provide good arch support, which impacts your entire body’s alignment, including your back.

Conclusion

Your back is a masterpiece of biological engineering, tirelessly serving as the central pillar of your existence. From the robust structure of your backbone and its 33 vertebrae to the intricate network of nerves and muscles, its anatomy is designed for power and precision. The marvel of its physiology allows for graceful movement, unwavering support, and the critical protection of your spinal cord.

By understanding the secrets of your spine, you gain the power to unlock its full potential and safeguard its health. Embrace good posture, strengthen your core, stay active, and listen to your body. Your back is a lifelong partner in your health and mobility; cherish it, nurture it, and appreciate the incredible journey it enables you to take every single day.

FAQ

Q1: What is the primary role of the backbone or spine?

A1: The primary role of the backbone (or spine) is to provide structural support for the body, allowing us to stand upright and maintain posture. It also enables a wide range of motion through its flexible design and, most critically, houses and protects the delicate spinal cord, which is the central communication pathway between the brain and the rest of the body.

Q2: How does the anatomy of the spine contribute to its physiology?

A2: The anatomy and physiology of the spine are intrinsically linked. The stacked vertebrae provide strength and protection, while the intervertebral discs act as shock absorbers and allow flexibility. The natural curves of the backbone (cervical and lumbar lordosis, thoracic kyphosis) are anatomical features that contribute to the physiological functions of weight distribution, shock absorption, and balance. Similarly, the network of ligaments and muscles stabilizes the back and facilitates its movement, showcasing how structure dictates function.

Q3: What is the difference between anatomy and physiology in the context of the back?

A3: Anatomy refers to the study of the structure of the back and its components—what it’s made of (bones, muscles, discs, nerves) and where these parts are located. For example, knowing there are five lumbar vertebrae is a point of anatomy. Physiology, on the other hand, is the study of how those anatomical structures function and work together. For instance, understanding how the lumbar vertebrae and discs work together to bear weight and allow bending is a matter of physiology.

Q4: How many natural curves does the human spine have, and what is their purpose?

A4: The human spine has three main natural curves: the cervical lordosis (inward curve in the neck), the thoracic kyphosis (outward curve in the upper back), and the lumbar lordosis (inward curve in the lower back). These S-shaped curves are crucial for the physiology of the back. They act like a coiled spring, distributing body weight, absorbing shocks from movement, increasing the spine’s flexibility and strength, and maintaining balance.

Q5: What role do intervertebral discs play in the back’s physiology?

A5: Intervertebral discs are vital for the physiology of the back. Their unique anatomy (tough outer ring and gel-like core) allows them to function as shock absorbers, cushioning the impact of daily activities like walking, running, and jumping. They also act as spacers between the vertebrae, facilitating the slight movements that contribute to the overall flexibility of the spine and preventing bone-on-bone friction.