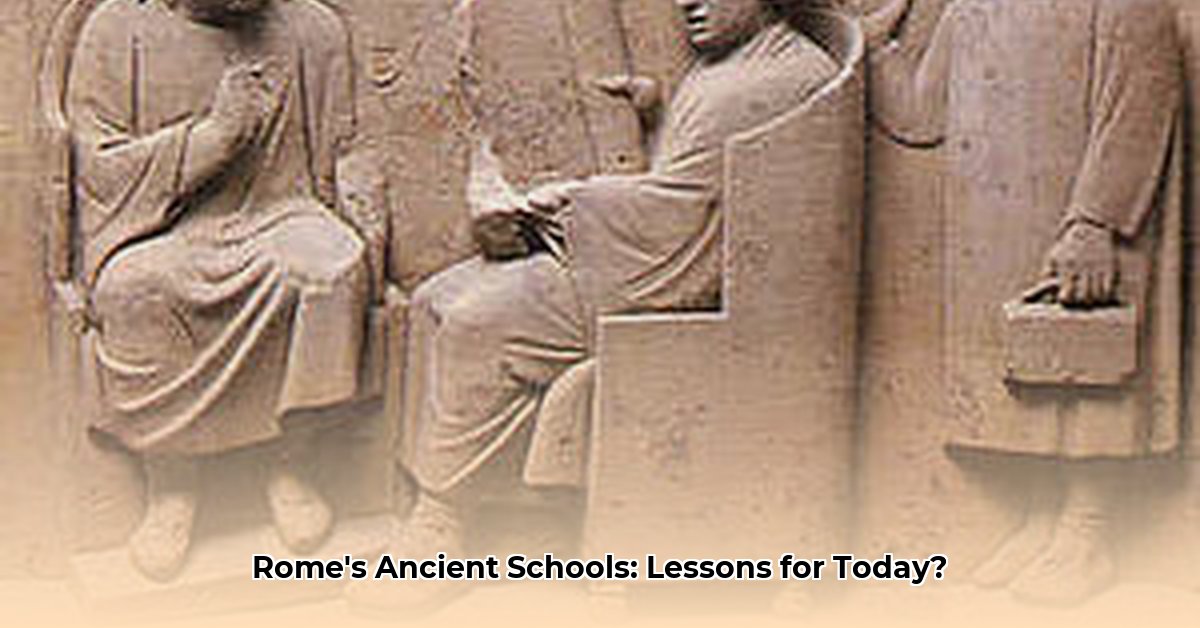

Embark on a captivating journey back to ancient Rome and explore its rich and evolving educational landscape. This article examines how the Roman education system transformed over centuries, its profound Greek influences, and its lasting impact on Western civilization. We will uncover the structured tiers of schooling, from foundational literacy to advanced rhetorical training, and reflect on the societal values, daily realities, and inherent inequalities that characterized ancient Roman pedagogy.

The Evolution of Roman Education: From Home to Formal Institutions

The system of education in ancient Rome underwent a remarkable transformation, evolving from an informal, family-centric approach in the early Republic to a highly structured, tuition-based system during the late Republic and the burgeoning Empire. This pivotal shift was significantly shaped by Rome’s increasing interaction with Greek culture and the dynamic changes within Roman society itself.

Early Beginnings: Family as the First Classroom

In Rome’s foundational period, the pater familias, the male head of the household, served as the primary and most influential educator. His instruction was deeply practical, focusing on imparting essential life skills to his sons, including agricultural practices, rigorous military discipline, and the civic responsibilities expected of Roman citizens. Daughters, on the other hand, were primarily educated by their mothers, who instilled in them the skills necessary for efficient domestic management, sewing, and running a household. This home-based approach underscored the Roman emphasis on pietas, a fundamental value encompassing duty, loyalty, and reverence for tradition, instilled from a very tender age.

Men like Cato the Elder exemplify this tradition, taking their teaching roles with utmost seriousness. Cato ensured his son was not only a hardworking and responsible Roman but also personally taught him reading, law, athletics—from javelin throwing and fighting in armor to riding a horse, boxing, enduring harsh weather, and swimming. This hands-on parental involvement highlights a distinct feature of early Roman moral and practical education. Even mothers, such as Cornelia Africana, the celebrated mother of the Gracchi brothers, were acknowledged for their crucial role in shaping their children’s character and eloquence.

However, as Rome expanded its dominion after the Punic Wars and engaged more deeply with the Hellenistic world, this traditional model began its inevitable evolution. Greek tutors, often highly educated enslaved individuals or freedmen, proliferated in Roman households. They introduced new academic disciplines, including sophisticated literature, intricate philosophy, and the nuanced art of public speaking. Figures like Livius Andronicus, a Greek captive from Tarentum who translated Homer’s Odyssey into Latin, were instrumental in integrating Greek educational practices into the very fabric of Roman culture. This marked a profound shift from a purely familial model to a more sophisticated, structured pedagogical system. What contemporary institutions or cultural shifts reflect a similar adaptability in integrating new knowledge and methodologies today?

The Tiered Structure of Roman Learning

Formal education in ancient Rome, predominantly available to the affluent classes, meticulously developed into distinct, progressive tiers, mirroring a system somewhat similar to modern educational progression:

- Ludus Litterarius (Primary School): Typically attended by children from ages seven to twelve, this foundational stage provided essential reading, writing, and basic arithmetic skills. The litterator (teacher) often carved alphabets into wooden boards for children to trace, and students learned numbers using pebbles (calculi) or an abacus. Lessons were often dictated, as books were expensive and rare. Discipline could be severe, with corporal punishment common for even minor errors, reflecting the Roman belief that fear hastened learning. Schools were often informal, held in rented rooms, shops (pergula), or even public spaces like street corners (trivium), exposed to the noise and bustle of daily Roman life.

- Grammaticus (Secondary School): From about ages nine to twelve, boys from affluent families, and occasionally some girls, transitioned to a grammaticus for deeper studies. This stage focused on grammar, Latin and Greek literature, poetic analysis, and elements of history and mythology. The curriculum was thoroughly bilingual, requiring students to read and speak in both Latin and Greek. Daily activities included lectures (narratio), expressive reading of poetry (lectio), and detailed analysis (partitio). Assessment was often on-the-spot, with teachers like Marcus Verrius Flaccus famous for using competitions and prizes (often rare books) to motivate students. This phase provided a robust foundation in classical learning, preparing students for higher intellectual pursuits.

- Rhetor (Rhetoric School): The final and most advanced stage, typically for students aged fourteen or fifteen and older, prepared aspiring politicians, lawyers, and public figures in the art of persuasive public speaking and argumentation, often referred to as rhetorical training. Very few students progressed to this level. The rhetor trained students not only in oratory but also in Roman law, politics, astronomy, geography, literature, philosophy, music, and mythology. This well-rounded curriculum ensured that future Roman leaders possessed a broad knowledge base. Exercises included declamations, mock speeches on invented themes for political or legal scenarios (suasoria for advice, controversia for legal arguments), designed to hone their persuasive skills. The orator’s role was crucial in Roman society, given its constant political strife and emphasis on public discourse. This advanced stage could be considered the ancient equivalent of higher learning institutions specializing in law, public policy, and communication.

This structured progression, though informal in its establishment (Rome never formally instituted state-sponsored elementary education), ensured that those with means received comprehensive training designed to equip them for leadership and influential roles within Roman society. The system, in part, functioned as a form of social control, as the monetary expenses inherently limited access, helping elites maintain class stability.

Access and Equity in Roman Education

Despite its advancements, education in ancient Rome was far from universally accessible. It remained largely a privilege determined by a family’s socioeconomic status and, significantly, gender. Teachers, particularly at the elementary ludus litterarius level, often faced financial struggles and typically held a lower social standing, seen more as tradesmen than revered professionals. The Edict on Maximum Prices issued by Diocletian in 301 CE, though largely unenforceable, illustrates the official attempt to fix salaries, with a litterator earning 50 denarii per pupil per month, a grammaticus 200 denarii, and a rhetor commanding even higher fees, reflecting the hierarchy of expertise. While formal schooling gained prominence, the emphasis on moral education and the instillation of values like pietas remained paramount, primarily through parental instruction.

Gender and Educational Opportunities

The question of how did Roman girls learn reveals a complex picture of societal expectations and limited, yet significant, educational opportunities. Early Roman society meticulously prepared girls for their designated future roles, primarily marriage and motherhood, which often occurred in their early teens. Formal public schooling was not the universal path for girls, yet it was not entirely absent. Affluent families frequently provided their daughters with basic literacy education, both from mothers and sometimes from private tutors, often Greek slaves. This foundational knowledge was essential for managing large households, keeping accounts, overseeing servants, and participating in Roman social circles. This practical approach often contrasted with the more civic and public-oriented curriculum for boys, highlighting distinct gender expectations.

While domesticity remained a central focus, a notable number of elite women demonstrated that advanced education was attainable. Hortensia, a celebrated Roman orator, stands out as a prime example of female intellectual prowess and effective rhetorical training, famously arguing a case before the Triumvirs. Educated wives and daughters of prominent Romans, such as Aurelia (Caesar’s mother) and Atia (Augustus’ mother), often displayed significant intellectual capabilities and served as integral intellectual companions to their husbands. Musonius Rufus, a Stoic philosopher, notably advocated for educational equality between genders, illustrating that debates about women’s roles and access to knowledge were ongoing within Roman society. However, prevailing concerns that excessive education might render women less desirable for marriage often meant that private tutors and self-education became common alternatives for continued learning, even after marriage.

Daily Life and Discipline in Roman Schools

Life for a Roman student was rigorous. Classes often began at dawn and concluded by noon, with no concept of a modern “weekend” but frequent religious holidays and market days providing breaks. There were no specific school buildings; classes convened in various informal settings. Students sat on backless stools, using waxed tablets for writing with a stylus, or sometimes broken pottery (ostraca) for exercises, as papyrus was expensive. Learning was highly individualized; students often worked independently, approaching the teacher one by one for instruction or to recite their lessons from memory. Competition was a constant, with performance measured by corrections or applause. Physical punishment, including caning or whipping, was a frequent and accepted method of discipline. This created an environment where students were constantly reminded of the consequences of errors, pushing them to learn quickly and accurately.

How Did Greek Methods Influence Roman Education System?

The trajectory of Roman education is, in many ways, a testament to astute cultural assimilation and adaptation. Initially, Roman upbringing centered squarely on the family, prioritizing practical know-how and honoring established ancestral customs. Yet, as Rome’s dominion expanded and its interactions with Greece intensified, a profound transformation began.

The Influx of Greek Pedagogy in Rome

The question of how did Greek methods influence Roman education system reveals an impact that was profound and systemic, not merely superficial. It manifested as a gradual yet deep integration, rather than a simple takeover. The Romans, ever pragmatic, swiftly recognized the immense value of Greek intellectual pursuits, particularly after direct exposure to Greek culture following the capture of Tarentum in 272 BC and the annexation of Sicily in 241 BC.

Greek tutors began to proliferate in affluent Roman households, bringing with them a highly structured and rigorous approach to learning. Grammar, literature (spanning both Greek and Latin, with Homer and Hesiod frequently used due to a lack of early Roman national literature), and rhetoric—the foundational pillars of Greek education—gained immense popularity among the Roman elite. This adoption was not solely about acquiring knowledge; it was fundamentally about cultivating the eloquence and persuasive skills deemed absolutely essential for success within Roman public life, including politics and law.

Rhetoric: A Roman Obsession

Rhetoric, defined as the art of persuasive speaking and argumentation, emerged as the paramount discipline in Roman higher education. In both the Roman Republic and successive Empire, the ability to skillfully sway an audience was considered paramount for political advancement, legal advocacy, and military leadership. Aspiring politicians, future lawyers, and statesmen flocked to rhetoric schools to meticulously hone their skills in argumentation, delivery, and stylistic mastery. One could aptly describe these institutions as the ancient Roman equivalent of a premier law school, focusing on the practical application of intellectual prowess.

Imagine young Roman men dedicating countless hours to practicing oratory, meticulously dissecting renowned historical speeches, and vigorously engaging in mock debates. Quintilian, a preeminent Roman educator and orator, extensively documented the ideal education required for a Roman orator in his work Institutio Oratoria, outlining a comprehensive curriculum for rhetorical training that emphasized character alongside skill. This profound emphasis on rhetoric fundamentally shaped Roman law, political discourse, and even its literary output, leaving an enduring imprint on the trajectory of Western civilization.

Adaptation, Not Mere Adoption

It is crucial to understand that the Romans were not simply blind imitators of Greek models. They judiciously adapted Greek methods to align with their distinct temperament and specific societal needs. While they eagerly embraced Greek intellectualism, particularly Greek literature, they maintained a certain pragmatic reserve toward aspects such as Greek athleticism and certain musical arts. To the Greeks, mousike (music, dance, lyrics, poetry) and athletics were fundamental to cultivating a well-rounded individual and a beautiful body (kalokagathia), ends in themselves. The Romans, however, often viewed music as morally corrupting and athletics primarily as a means to maintain good soldiers, not for beauty or competition for its own sake. Their approach was highly selective, tailoring borrowed concepts to fit their unique Roman context of governance and empire building.

For instance, Roman law schools emerged as a distinct and highly specialized form of higher education, diverging significantly from Hellenistic models. These institutions meticulously trained future jurists and lawyers in Roman law, jurisprudence, and precise legal procedure. This development clearly reflected the deep Roman emphasis on order, effective governance, and unwavering legal precision, marking a unique contribution to the ancient curriculum. Another unique aspect was the tirocinium fori (apprenticeship in the Forum) and tirocinium militiae (military apprenticeship), where young men attached themselves to experienced senators, jurists, or generals to gain practical experience in law, administration, and war—knowledge not formally taught in schools.

A Lasting Cultural Legacy

The sophisticated fusion of Roman practicality and Greek intellectualism gave rise to a unique educational system. This system not only shaped the Roman elite but also significantly contributed to the empire’s enduring success. So, how did Greek methods influence Roman education system so profoundly? They provided the fundamental framework for formal schooling, a central focus on rhetorical training, and a comprehensive curriculum firmly rooted in classical learning. This far-reaching legacy extended well beyond the dissolution of the Roman Empire, consistently influencing the development of education in the Western world for many centuries. The echoes of ancient Roman classrooms and the formidable voices of Roman orators continue to resonate distinctly within our contemporary educational systems and legal traditions. It makes you wonder, doesn’t it, just how deeply rooted our own modern educational frameworks are in these ancient traditions? It’s a fascinating thought, isn’t it?

| Feature | Ancient Greek Education | Ancient Roman Education |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Cultivation of well-rounded citizens (philosophy, arts, physical) | Training of effective leaders, orators, administrators, and citizens (practical, civic, rhetorical) |

| Core Curriculum | Philosophy, mousike (music, poetry, dance), gymnastics, rhetoric, logic, mathematics | Latin & Greek grammar, literature, rhetoric, law, history, basic arithmetic |

| Accessibility | Varied by city-state; often more community-based, but still class-dependent | Predominantly class-dependent; formal schools were tuition-based private institutions |

| Gender Access | Boys typically educated formally; girls mostly home-schooled, but some exceptions | Boys had greater formal opportunities; girls mostly home-schooled for domestic skills, though elite girls sometimes received advanced private tutoring |

| Pedagogical Ethos | Emphasis on intellectual pursuit, beauty, paideia (holistic education) | Emphasis on practicality, civic duty, discipline, and effective public performance |

| Key Figures | Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Pythagoras | Cato the Elder, Livius Andronicus, Quintilian, Cicero, Musonius Rufus |

Ancient Rome: Tiered Educational Structure – and Curriculum Unveiled

The Roman educational system stands as a testament to a society that, while not mandating universal schooling, progressively embraced formal learning to cultivate its elite and maintain its vast empire. This section delves into the precise mechanics of Ancient Rome’s tiered educational structure and curriculum.

From Domestic Instruction to Structured Schooling

Initially, the Roman father held the primary responsibility for a child’s education, diligently instilling moral principles, disciplined behavior, and practical skills. As Roman society evolved, particularly from the 3rd century BCE onwards, wealthier families began to employ private tutors, often of Greek origin, who introduced children to a broader array of subjects and a more systematic approach to learning. For less affluent families, access to basic schooling was sometimes possible, with a focus on core literacy and fundamental mathematical skills. This foundational learning was crucial for daily life and basic commerce, evidenced by widespread wall scribblings in Pompeii.

The Comprehensive Ladder of Learning

The profound integration of Greek educational methods fundamentally reshaped Roman pedagogy, leading to the establishment of more structured schools and specialized academies. While formal education was never legally compulsory, it became an expected standard for elite boys, particularly those aspiring to careers in public service, law, and politics. This expectation solidified the concept of a rigorous, multi-stage ancient curriculum for the upper classes. So, how precisely did this tiered educational system operate, and what constituted its curriculum at each level?

-

The Ludus Litterarius (Primary School):

- Age Group: Approximately 7 to 11/12 years old.

- Teacher: The litterator.

- Curriculum: Focused on the “Three Rs”: reading, writing, and basic arithmetic. Children learned to form letters by tracing them carved into wooden boards, progressed from syllables to words, and eventually memorized and dictated texts, often from Greek poetry like Homer or Hesiod due to the scarcity of early Roman literature. Arithmetic involved counting on fingers, with pebbles (calculi), and using an abacus. Chanting was used for addition and multiplication tables.

- Learning Environment: Informal, often held in rented rooms, converted shops (pergulae), or even noisy public spaces like street corners (trivium). Students sat on backless stools, using wax tablets (tabulae ceratae) and a stylus, or broken pottery (ostraca) for exercises. Books were rare and expensive.

- Discipline: Known for its severity, with teachers like Lucius Orbilius Pupillus (Horace’s teacher) famous for flogging students. The belief was that constant fear of mistakes encouraged quick and accurate learning.

- Progression: Performance was measured by immediate correction or applause, fostering a competitive atmosphere. Many children, especially from poorer families, would not advance beyond this stage, equipped only with the practical literacy needed for basic employment.

-

The Grammaticus (Secondary School):

- Age Group: Approximately 11/12 to 14/15 years old.

- Teacher: The grammaticus.

- Curriculum: Students delved deeply into classical literature, both Latin (e.g., Ennius, Virgil) and Greek (e.g., Euripides, Homer). Daily activities included lectures (narratio), expressive reading of poetry (lectio), and detailed literary analysis (partitio). The curriculum was thoroughly bilingual. Students also began to learn philosophy, astronomy, and natural science, and honed their writing and speaking skills through exercises like paraphrasing and character sketches, often engaging in lively discussions.

- Teacher Status: More prestigious than the litterator, with higher potential earnings. Famous grammatici included Marcus Verrius Flaccus, known for innovative teaching methods like competitive learning.

- Objective: To provide a robust foundation in classical learning and critical thinking, preparing students for the advanced studies of rhetoric.

-

The Rhetor (Rhetoric School):

- Age Group: Approximately 15 to 20 years old, or even later.

- Teacher: The rhetor.

- Curriculum: The apex of Roman education, focused intensely on the art of persuasive public speaking (rhetoric). Students received comprehensive training in argumentation, delivery, and stylistic mastery, essential for careers in law and politics. Key exercises included declamations—fictitious speeches on historical or legal themes. These often comprised suasoriae (speeches advising historical characters) and controversiae (debates on points of law), allowing students to practice oratory in a practical context. Beyond rhetoric, the curriculum was holistic, covering Roman law, politics, history, geography, music, philosophy, and mythology.

- Teacher Status: The most respected and highest-paid teachers in the educational hierarchy, commanding significant influence over their elite students.

- Objective: To cultivate skilled orators and statesmen capable of leading in the Roman Forum, the Senate, and the courts. This was considered the direct path to public success.

The Gender Divide: Who Received Formal Education?

Girls in ancient Rome faced considerably restricted access to formal public learning institutions. While daughters from wealthy families might receive instruction from private tutors within the home, or even attend ludus litterarius for basic literacy, the primary focus of their education remained geared towards domestic skills (spinning, weaving, household management), rather than the advanced rhetorical training pursued by boys. Prevailing societal norms largely confined women to household roles, which significantly influenced the scope and nature of their educational opportunities. By the time boys advanced to grammaticus and rhetor schools, most girls, rich or poor, would be focused on preparing for marriage and motherhood, often marrying as early as age 12. This stark contrast highlights the significant gender disparities in educational access.

Unequal Access, Enduring Influence

While Roman education demonstrated considerable advancement for its time, it was fundamentally characterized by significant inequalities. A student’s wealth largely dictated their access to quality instruction, thereby perpetuating existing social divides. Furthermore, limited formal opportunities for women reinforced established gender roles. Nevertheless, the unwavering Roman emphasis on literacy, their systematic development of rhetorical training, and their structured pedagogical approach profoundly shaped the trajectory of Western education for centuries to come, laying foundations for our own classical learning traditions. The Roman system, in its blend of the practical and the intellectual, continues to offer valuable insights into the enduring challenges and timeless principles of education.

Present-Day Lessons from Roman Pedagogy

- The Value of Rhetoric and Eloquence: In an age saturated with information, the Roman emphasis on clear, persuasive communication and critical argumentation remains profoundly relevant. Modern communication courses and public speaking training can draw directly from Roman rhetorical principles.

- Addressing Educational Disparities: The stark educational inequalities in ancient Rome, based on socioeconomic status and gender, serve as a historical mirror reflecting ongoing challenges in contemporary access to quality education. Understanding these historical precedents can inform policymakers and educators working towards equitable learning opportunities today.

- Holistic Development and Practical Skills: Beyond academic subjects, Roman education’s focus on moral values (pietas), civic duty, and vocational training (e.g., military skills, apprenticeships) underscores the importance of a well-rounded education that prepares individuals for both intellectual and practical life.

- Teacher Status and Support: The varying social status and remuneration of Roman teachers highlight the perennial importance of valuing and fairly compensating educators to attract and retain talent in the profession.

Further research into ancient Roman teaching methods, the lives of students and teachers, and specific literacy rates across different social strata may uncover additional insights for improving pedagogical practices and fostering equitable access to quality learning in our own complex societies. What can a closer look at their challenges teach us about fostering equitable access to quality learning now?