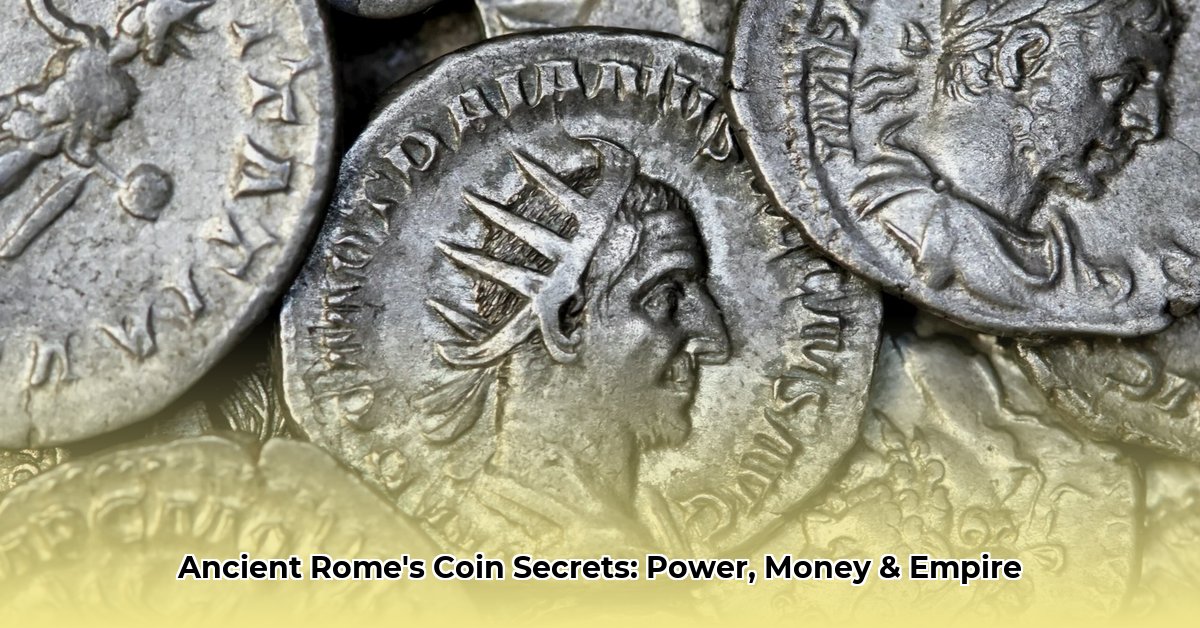

The subtle sound of coins in ancient Rome speaks volumes—a narrative far richer than simple commercial transactions. These metallic discs, evolving from rudimentary bronze chunks to the widely circulated silver denarius, were powerful instruments that ignited an empire, sustained vast armies, and even broadcast an emperor’s latest decrees or meticulously crafted image. Learn more about the power of coinage in Roman history. More than mere units of exchange, Roman currency served as a dynamic tool of power, a tangible canvas for state propaganda, and ultimately, a silent witness to the Roman Empire’s grand ascendance and eventual decline. For those captivated by ancient history, the intricacies of the Roman economy, or the foundational principles of monetary systems, understanding these coins unlocks pivotal insights into one of the most influential civilizations the world has ever known.

From Barter to a Standardized Monetary System

Early Rome, a burgeoning city-state, conducted its economy primarily through direct exchange—bartering livestock for grain, or perhaps raw bronze for timber. This rudimentary system, while functional for a localized agrarian society, quickly proved unwieldy as Rome’s influence expanded beyond its immediate vicinity. The increasing complexities of managing growing territories, provisioning an expanding urban population, and financing continuous military campaigns demanded a far more sophisticated and efficient method of trade and governance.

The Dawn of Roman Coinage

Around 300 BCE, a transformative shift occurred: Rome began to embrace formalized coinage, marking a fundamental economic revolution. This transition did not happen overnight, nor was it a singular, unified event. Initially, Rome experimented with various forms of metallic currency:

- Aes Rude: These were rough, unworked chunks of bronze, valued by weight rather than by denomination. They represented Rome’s earliest step beyond pure barter.

- Aes Signatum: Appearing around the 4th century BCE, these were large, cast bronze ingots, sometimes bearing rudimentary designs or markings. They were standardized in weight and shape, typically weighing between 1.5 to 1.6 kilograms, representing an early attempt at formalizing metallic currency, predating true struck coinage.

- Aes Grave: Introduced roughly contemporaneous with the formal adoption of coinage around 300 BCE, these were substantial, cast bronze coins. Unlike the later struck coins, aes grave pieces were produced by pouring molten bronze into clay molds, resulting in often crude, asymmetrical shapes but standardized weights. The primary denomination was the as, weighing approximately one Roman pound (libra), with fractional units like the semis (half) and quadrans (quarter).

These early systems, alongside a series of bronze and silver coins known as “Romano-Campanian” issues, laid the groundwork for a sophisticated Roman monetary system. This system would profoundly impact economic thought and practice across Western Eurasia and North Africa for centuries. The legacy is still palpable today: the term “dinar” directly descends from the Roman denarius, and the British “pound” traces its origin to libra, a Roman unit of weight. This enduring linguistic imprint speaks volumes about the lasting influence of Roman economic innovations.

The Catalytic Impact of Conflict

Interestingly, Rome was somewhat of a latecomer to the practice of standardized coinage compared to other ancient Mediterranean civilizations. Greeks in Asia Minor had pioneered the use of struck coins as early as the 7th century BCE. Historians suggest that pivotal events, particularly the monumental Second Punic War (218–201 BCE) against Carthage, served as a crucial catalyst for Rome’s full embrace of a comprehensive coinage system. The immense financial demands of sustaining a prolonged, empire-wide conflict underscored the urgent need for a robust and trustworthy monetary system to manage military expenditures, supply lines, and taxation efficiently. This delayed but definitive adoption ultimately proved indispensable for Rome’s ambitious imperial expansion.

The Imperial Mint: Forge of Power and Propaganda

The very word “mint,” signifying a place where money is produced, owes its etymology to ancient Rome’s Temple of Juno Moneta on the Capitoline Hill. These Roman mints, strategically situated across the vast empire, were far more than mere factories stamping out coins. They served as vital propaganda machines, churning out coinage emblazoned with imperial images and carefully crafted messages.

Every coin issued became a miniature, mobile billboard, meticulously designed to convey the emperor’s authority, celebrate his military victories, or promote his dynastic legitimacy. Consider the brief reign of Quietus, a usurper during the tumultuous third century CE. Despite ruling only a portion of the empire from 260 to 261 CE, he swiftly issued thirteen distinct types of coins featuring his likeness from three different mints. This immediate production underscores how integral coinage was to projecting power and shaping public perception during rapidly changing political landscapes. These coins were not merely financial instruments; they were powerful tools for influencing popular sentiment and consolidating the ruler’s narrative.

Imperial Portraits: A Shifting Canvas

The evolution of Roman currency, particularly the denarius, beautifully illustrates the empire’s journey from a republic of austere values to an autocratic imperial power.

During the Republican era, coin designs typically featured venerable mythological scenes, stoic deities, or personifications of Roman virtues. This changed dramatically with Julius Caesar. Breaking with centuries of tradition, he became the first living Roman to place his own portrait on circulating coinage in 44 BCE. This audacious move was a clear act of self-promotion, a means to broadcast his image and political agenda directly to the populace, a revolutionary moment in Roman numismatics.

Under the Empire, the practice of depicting the living emperor’s face on coins became standard. This constant visual reinforcement served as a powerful reminder of who held ultimate authority, cementing the emperor’s power and, in some cases, even hinting at his divine status or special relationship with particular deities. Imperial family members, such as empresses and heirs apparent, were also frequently featured, further fortifying dynastic claims and imperial legitimacy. As the Stoic philosopher Epictetus observed, coins carried a certain “moral weight,” reflecting the virtues—or perceived absence thereof—of the individual depicted upon them. These emperor portraits were, therefore, an unparalleled form of propaganda, communicating the ruler’s agenda with ubiquitous precision. The stylistic changes in these portraits, from the idealized forms of Augustus to the stark, often stern realism of later military emperors, offer profound insights into the aspirations and insecurities of their imperial patrons throughout different eras.

The Denarius: Backbone of an Empire, Victim of Debasement

The denarius, a silver coin first introduced around 211 BCE, rapidly became the unwavering standard of the Roman economy. Initially weighing approximately 4.5 grams of nearly pure silver, it facilitated every conceivable transaction, from soldier’s pay (reportedly 10 denarii for a legionary’s daily wage by the late Empire, though vastly inflated) to complex marketplace purchases. It was initially valued at 10 asses, hence its name, but was revalued to 16 asses in 141 BCE.

| Coin | Material & Era | Key Features & Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Denarius | Silver (Republic/Empire) | The primary silver coin from 211 BCE, equivalent to approximately 4 sestertii. Initially pure, its metal content gradually declined over centuries due to debasement, enduring until the mid-3rd century CE. Its name lives on in “dinar” and “dinero.” |

| Aureus | Gold (Empire) | Introduced in the 1st century BCE, this gold coin initially weighed about 8 grams and was equivalent to 25 denarii. It served as the highest-value coin, primarily used for large government payments and imperial transactions, remaining relatively stable in purity longer than the silver denominations. |

| Sestertius | Bronze/Orichalcum (Republic/Empire) | A large, impressive bronze (later orichalcum, a brass-like alloy) coin, initially worth 2.5 asses. It was widely used for daily purchases and a common unit of account, often featuring detailed reverse imagery. Its substantial size made it a popular medium for conveying imperial messages through its artwork. |

| Antoninianus | Silver (at first) (Empire) | Introduced by Emperor Caracalla in 215 CE, this coin was nominally valued at two denarii and identifiable by the radiate crown worn by the emperor’s portrait. However, it rarely contained more than 1.6 times the silver of a denarius and rapidly lost value due to aggressive debasement during the Crisis of the Third Century, quickly replacing the denarius as the dominant silver coinage before itself becoming almost entirely bronze. |

| Solidus | Gold (Late Empire) | Introduced by Constantine the Great in 312 CE. Struck at a stable weight of 4.5 grams of nearly pure gold, the solidus became the new gold standard for the rest of the Roman and Byzantine Empires, providing a much-needed stable currency for larger transactions amidst widespread debasement of base metal coins. |

The Unraveling of Trust and Value: Debasement

This very backbone of Roman finance would eventually weaken. Over time, the silver purity and weight of the denarius steadily diminished—a process known as debasement. Emperor Nero, in 64 CE, notoriously reduced the silver content of the denarius from 98% to 90%, setting a dangerous precedent for future currency devaluation. This trend continued relentlessly, with Septimius Severus reducing it to around 50%, and by the mid-3rd century CE, the denarius contained merely 5% silver, making it virtually worthless.

The antoninianus, intended by Emperor Caracalla to be a double denarius, met an even faster decline, quickly losing its intended value and eventually becoming little more than a bronze blank with a silver wash. By the mid-3rd century, the denarius was rarely minted, essentially becoming obsolete. Even Emperor Aurelian’s vigorous monetary reforms in 274 CE, which attempted to restore a 5% silver content to the antoninianus (indicated by the “XXI” mark, meaning 20 parts copper to 1 part silver), could not entirely halt this systemic decline.

What drove this continuous reduction in value? A complex interplay of factors:

- Rampant Inflation: The reduction in precious metal content directly caused prices to skyrocket, diminishing the purchasing power of citizens and destabilizing the economy. As economist J. Wisniewski noted, “By the third century A.D., Roman coin was a bad joke whose actual precious metal content was questionable at best. Things got so bad that the Roman government wouldn’t accept tax payments in its own currency.”

- Military Demands and Fiscal Desperation: Emperors, facing relentless pressures from constant warfare—such as Septimius Severus’s costly military campaigns—and unforeseen calamities like the devastating Antonine Plague of 165 CE, often resorted to debasement as a desperate measure. The logic was simple: stretch the available silver supply to mint more coins, enabling them to pay massive armies and keep a vast empire running. This recurring need to finance extensive military operations was a primary driver behind the persistent reduction in the denarius‘s intrinsic value, creating a vicious cycle of increasing military costs and diminishing currency worth.

- Lack of Precious Metals: Rome’s ability to acquire new sources of gold and silver through conquest diminished significantly after the 1st century CE. Mines became exhausted, and persistent trade deficits with the East, particularly India, drained precious metals from the Roman economy.

- Gresham’s Law: As Bruce Bartlett articulated, Gresham’s Law—”bad money drives out good”—played a significant role. People hoarded older, high-silver-content coins and paid their taxes or debts with the newer, debased coinage, further exacerbating the circulation of low-value currency and reducing the state’s “real” revenue.

- Systemic Erosion of Trust: Debasement gradually destroyed public confidence in the currency, leading to widespread distrust among merchants and citizens. This unstable currency made long-distance trade risky and unpredictable, causing foreign merchants to hesitate in accepting Roman coins, thus hindering economic growth and connectivity. Cicero himself alluded to a currency crisis around 86 BCE, noting, “The coinage was being tossed around, so no one was able to know what he had.”

Here’s an overview of the pros and cons of Roman currency debasement:

| Aspect | Pro (Short-Term & Imperial Perspective) | Con (Long-Term & Societal Perspective) |

|---|---|---|

| Fiscal Management | Provided immediate funds to meet pressing imperial expenditures, such as military pay, infrastructure projects, and administrative costs, without directly raising taxes. | Fueled runaway inflation, eroding the purchasing power of the populace and destabilizing the entire economy. It effectively acted as a hidden tax on cash balances, disproportionately affecting the poor. |

| Money Supply | Allowed the government to increase the money supply rapidly, facilitating large-scale transactions and payments necessary for a vast empire. | Led to a systemic erosion of public trust in the currency, making people reluctant to accept coins at face value and causing a flight to real assets (land, commodities) or hoarding of older, purer coins. |

| Economic Impact | Maintained liquidity for the imperial government, especially during times of crisis and warfare, helping to prevent immediate financial collapse. | Disrupted long-distance trade relationships as foreign merchants became wary of accepting devalued Roman coins, hindering economic growth and leading to a more localized, less dynamic economy. |

| Social Cohesion | Temporarily alleviated budget deficits, delaying direct and potentially unpopular tax increases. | Contributed to widespread economic hardship, social unrest (e.g., mob riots during the Imperial Crisis), and a sense of injustice, weakening the bond between the government and its citizens. |

| Longevity | – | Ultimately contributed to the fragmentation of the Roman economy, the decline of banking systems (as seen during Gallienus’s reign), and is widely considered a factor in the Western Roman Empire’s decline. |

The Struggle for Stability: Later Imperial Reforms

The Romans, despite their engineering and military prowess, lacked a sophisticated understanding of modern monetary policy. They tended to view debasement as a quick, temporary fix for immediate financial crises, rather than recognizing its long-term detrimental effects. Emperor Diocletian, for instance, attempted to stabilize the currency in ancient Rome by introducing new, more standardized coins (like the argenteus and follis) and issuing the Edict on Maximum Prices in 301 CE to curb rampant inflation. However, many historians agree these efforts were largely unsuccessful, often collapsing within years due to market forces and the continued presence of debased older coins in circulation.

Later, Constantine I’s introduction of the solidus in 312 CE provided a stable gold coin, struck at a consistent weight and purity for centuries. While the solidus became the backbone of the Byzantine Empire’s economy, it did not fully reverse the centuries of monetary instability for the broader Roman economy that relied heavily on silver and bronze coinage, suggesting a growing economic divide between the gold-rich elite and the general populace.

A Lasting Legacy: Echoes of Roman Coinage

The denarius, along with its counterparts like the sestertius, aureus, and later the solidus, formed the indispensable backbone of the Roman economy for centuries. The denarius, in particular, transcended its origins to become a de facto international currency, facilitating trade across vast networks and connecting disparate regions under Roman influence. Its reach was so profound that in 2023, a scuba diver discovered tens of thousands of astonishingly well-preserved Roman-era bronze coins off the Italian coast of Sardinia, a testament to their widespread circulation.

Today, Roman coins are coveted by numismatics enthusiasts and revered by museums worldwide. They are far more than mere ancient artifacts; they are tangible pieces of history, offering palpable connections to the daily lives, grand ambitions, and daunting challenges faced by the fascinating people who built and lived within the Roman Empire. These small, often intricate pieces of metal serve as enduring reminders of Rome’s unparalleled greatness and its complex, lasting impact on the world, a legacy still resonating in our language, our concepts of finance, and our enduring fascination with the ancient past.