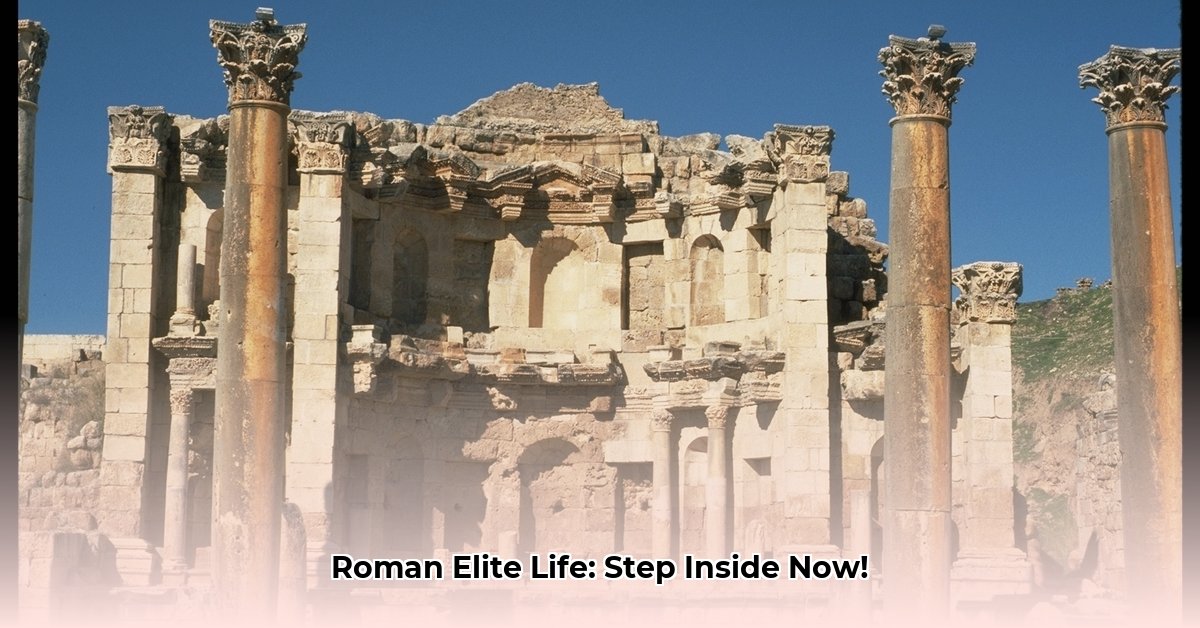

Imagine stepping into a world where luxury was not just seen but felt, where the air was thick with the scent of roasted delicacies, exotic spices, and fine wine. Oil lamps, a luxury in themselves, cast dancing shadows across intricately painted walls, as household slaves moved with practiced grace, ensuring every detail was perfect. This was the scene within the Roman triclinium – more than just a dining room, it was the meticulously designed stage for ancient Rome’s most significant social rituals, a place where reputations ascended or crumbled, and power was subtly asserted. Planning a party like this involved immense coordination; learn more about ancient Roman parties here. Join us as we unveil the secrets of this remarkable space, where reclining was an art form, social customs dictated every gesture, and each meal became a lavish performance of wealth, influence, and connection.

Unveiling the Roman Triclinium: The Heart of Elite Social Life

The triclinium was far from a mere utilitarian space for eating; it embodied a powerful symbol of status and served as the primary arena for social interaction within affluent Roman homes. Its very name, derived from the Greek triklinion (from tri- meaning “three” and klinē referring to a couch), precisely describes its iconic configuration: three dining couches, known as lecti (singular lectus), arranged around a low square table, leaving the fourth side open for service. This architectural design, a refinement of earlier Greek and Etruscan customs, fostered lively conversation and a sense of intimate communal connection among dinner guests, making it central to Roman domestic life.

The Ritual of Reclining: A Distinct Roman Adaptation

The practice of reclining while enjoying a meal, a tradition that became deeply ingrained in Roman aristocratic culture, held significant social meaning. Adopted from the Greeks in the early seventh century BC and subsequently refined through Etruscan influence, the Romans embraced this custom with their own unique flair. A notable departure from Greek traditions, which typically confined formal banqueting to male guests in an andrōn, was the Roman inclusion of women and even children in their triclinia. This distinct approach highlighted a more inclusive, albeit still hierarchical, aspect of Roman family and social life within formal settings. Reclining was not merely for comfort; it was a public declaration of the host’s immense wealth and the leisurely lifestyle afforded to the Roman elite, a stark contrast to the upright seating common among the working classes who lacked the means or time for such elaborate leisure.

A Night in the Triclinium: An Ornate Social Spectacle

As the Roman sun began its descent, casting long shadows across the city, privileged guests would arrive at the dominus‘s villa for an evening that often lasted from late afternoon until deep into the night. Every element of the social gathering was meticulously orchestrated. The host, often a prominent pater familias, presided over the intricate seating arrangements, strategically placing the nine to twenty invited guests to reflect both their social standing and their personal relationship with him. The most esteemed positions, offering prime views and close proximity to the host, were reserved for the most important guests – those whose patronage was sought, or whose elevated status augmented the host’s own public image.

The meal itself commenced as a lavish procession of multiple courses, brought from the adjacent culina (kitchen) by household slaves. The air was thick with the rich aromas of expertly prepared roasted meats, freshly baked bread, an abundance of vegetables and fruits, and exotic spices imported from distant corners of the Empire. Fine wine, always mixed with water as a sign of refinement (often in ratios like 1:2 or 1:3), flowed freely, encouraging spirited conversation and convivial atmosphere. The entertainment was as varied as it was captivating: skilled poets might recite epic verses, musicians play the lyre or a cithara, dancers captivate with their movements, or acrobats mesmerize the attendees. As the evening progressed, discussions typically gravitated towards the pressing politics of the day, complex business dealings, and the latest societal intrigues and gossip. The continuous burning of numerous oil lamps, a costly commodity, cast an ethereal glow, silently underscoring the host’s ability to spend lavishly on such grand banquets, further showcasing their immense affluence. It was a multi-sensory experience – a night of gastronomic pleasure, intellectual discourse, and a subtle yet powerful performance of influence and social status.

The Triclinium and Social Class: A Stark Symbol of Power

More than a mere dining area, the triclinium served as a profound physical manifestation of the vast societal chasm separating Rome’s wealthy elite from its common citizens. While the Roman aristocracy reclined in unparalleled luxury, indulging in elaborate multi-course meals and sophisticated entertainment, the vast majority of Roman citizens, particularly the working class, lived a far more modest existence, often toiling relentlessly just to meet basic needs. The very existence of a dedicated triclinium, let alone multiple ones within a single household (it was not unusual for elite homes to have four or more), was a tangible reminder of this profound social disparity. It was a space where the elite could ostentatiously flaunt their wealth, unequivocally reinforcing their elevated social standing and cementing their position at the pinnacle of the social hierarchy. Smaller triclinia were used for more exclusive sets of guests, often with equally elaborate decoration, highlighting different tiers of social connection.

Evolution and Variations: Adapting Roman Dining Layouts

Over the centuries, the architectural and design aspects of the triclinium underwent significant evolution, reflecting shifting societal tastes and the evolving needs of Roman social life. Initially, these formal dining rooms predominantly featured the three separate couches (lecti) arranged around the central table, often sloping slightly away from the table for comfort. However, by the later Republican period, especially after the introduction of round tables made of luxurious citrus wood, the layout began to transition. The traditional three couches were sometimes replaced by a single, crescent-shaped seating arrangement known as a sigma (from the Greek letter’s form). This sigma typically accommodated five persons, offering a more integrated and communal dining experience, and continued in use well into the Middle Ages.

Moreover, the decoration of triclinia varied immensely, reflecting the host’s personal preferences, intellectual inclinations, and, of course, financial capacity. Hosts frequently incorporated elaborate mosaics, detailed frescoes, and elegant sculptures, transforming the walls into vibrant canvases that showcased their unique artistic tastes and created distinct atmospheres for their social gatherings. Popular decorative themes included Dionysus (Bacchus), the god of wine and revelry; Venus, the goddess of love and beauty; and still lifes depicting food, reflecting the room’s primary purpose. For more “serious” gatherings or those involving recitations of highbrow literature, dining rooms might feature themes of heroes and epic exploits, highlighting the owner’s sophisticated literary leanings. Remarkably preserved reconstructions, such as those at the Museum of Archaeology in Arezzo, Italy, and the House of Cairo in Pompeii, offer invaluable glimpses into the opulent and varied designs of these ancient spaces.

Decoding the Seating Arrangement: The Locus Consularis

The seating within a Roman triclinium was a meticulously planned system designed to visually express and reinforce social hierarchy, far from an arbitrary arrangement. The three reclining couches were typically designated as lectus summus (the highest couch), lectus medius (the middle couch), and lectus imus (the lowest couch). Within each couch, specific positions held varying degrees of prestige. The locus consularis, considered the most prestigious seat, was strategically positioned to allow high-ranking officials or honored guests direct access to the host’s immediate circle, facilitating political and business discussions. The host himself traditionally occupied the locus imus on the lectus imus, enabling him to oversee the serving and manage the flow of the banquet effectively. Guests were then precisely placed on the lectus summus and lectus medius according to their importance, proximity to the host, and social standing. This precise arrangement not only reinforced the intricate social order but also served as a constant, subtle reminder of the power dynamics at play within the triclinium.

The Triclinium’s Enduring Legacy

The ancient Roman triclinium cast a profound and lasting influence on subsequent European dining customs, a legacy still discernible in modern traditions. The very concept of a dedicated, formal dining room, complete with meticulously planned seating arrangements, an emphasis on multi-course meals, and a focus on social interaction, stands as a direct descendant of this unique ancient Roman institution. Even the enduring cultural significance we place on sharing food and drink as a cornerstone of social bonding, celebration, and networking can trace its roots back to the highly structured and performative world of the triclinium. As you next gather for a formal dinner, pause for a moment to consider the profound and often overlooked influence of this truly remarkable Roman space on our contemporary banqueting traditions.

The triclinium was more than just a room; it was a microcosm of Roman society, reflecting its social stratifications, its cultural adaptations, and its enduring emphasis on public display and power. Through archaeological finds and historical texts, we continue to piece together the fascinating story of these elite dining rooms, allowing us to step back in time and virtually experience the splendor and significance of ancient Roman hospitality.