Ever wondered what it was truly like to be a student in ancient Rome, a world vastly different from our digitally-driven classrooms today? Imagine a society where education was a mosaic, beginning intimately within the family, profoundly shaped by the intellectual currents of Greece, and culminating, for a select few, in the powerful artistry of rhetoric. Ancient Roman schooling was not a static system but a dynamic, multi-layered journey, evolving from the domestic hearth to structured institutions. It was a path that led from mastering foundational literacy to crafting persuasive speeches capable of influencing senates and forging an empire. By exploring this rich historical landscape, we uncover more than just facts; we find a profound mirror reflecting our ongoing educational challenges and triumphs. Want to learn more? Read about ancient Roman schools here.

The Genesis of Roman Learning: From Domesticity to Formal Instruction

Early Roman education, particularly during the Republic, was predominantly a family affair. The pater familias, the esteemed head of the household, bore the primary responsibility for the upbringing and instruction of his children. This familial emphasis ingrained essential life skills, rigorous moral codes, and a deep sense of civic duty, known as pietas—devotion to the state, family, and gods. Figures like Cato the Elder exemplify this tradition, personally educating his son in everything from reading and law to javelin throwing and horsemanship. Mothers, like Cornelia Africana, were also pivotal in shaping their children’s character and eloquence. This home-centered approach, steeped in character formation and practicality, formed the bedrock of early Roman values.

However, as Rome expanded its dominion and its interactions with other vibrant cultures intensified, particularly following the pivotal Punic Wars, this intimate model began to transform. The inherent practicality of Roman society gradually began to blend with a burgeoning intellectual curiosity, profoundly influenced by external forces.

The Greek Catalyst: Forging a New Educational Paradigm

The profound influence of Greek culture undeniably reshaped Roman learning. From the 3rd century BCE, with events like the capture of Tarentum, Roman society was increasingly exposed to Greek thought and lifestyle. Greek tutors, often enslaved or freed individuals like Livius Andronicus (who translated Homer’s Odyssey into Latin), introduced a more structured and intellectually rigorous approach. These educators brought with them a focus on literature, philosophy, and sophisticated rhetoric, effectively sparking the development of formal, tiered educational institutions in Rome.

This cultural exchange transcended mere importation; it involved a careful adaptation of Greek ideas to align with Roman sensibilities. While the Greeks often reveled in abstract thought, the pursuit of beauty, and the arts (such as mousike—a combination of music, dance, lyrics, and poetry), Roman education re-centered around the practical application of knowledge. Music, integral to Greek paideia, was often dismissed by Romans as conducive to moral corruption. Athletics, for Greeks an end in itself promoting physical beauty and competition, was viewed by Romans primarily as a means to maintain strong soldiers. For Romans, an area of study was valuable only insofar as it served a clear, utilitarian purpose, particularly the art of persuasion crucial for public life and the maintenance of the state.

Ascending the Ranks: The Multi-Tiered Roman School System

The educational journey in ancient Rome generally followed distinct stages, each building upon the last, though access was profoundly influenced by socioeconomic standing and gender.

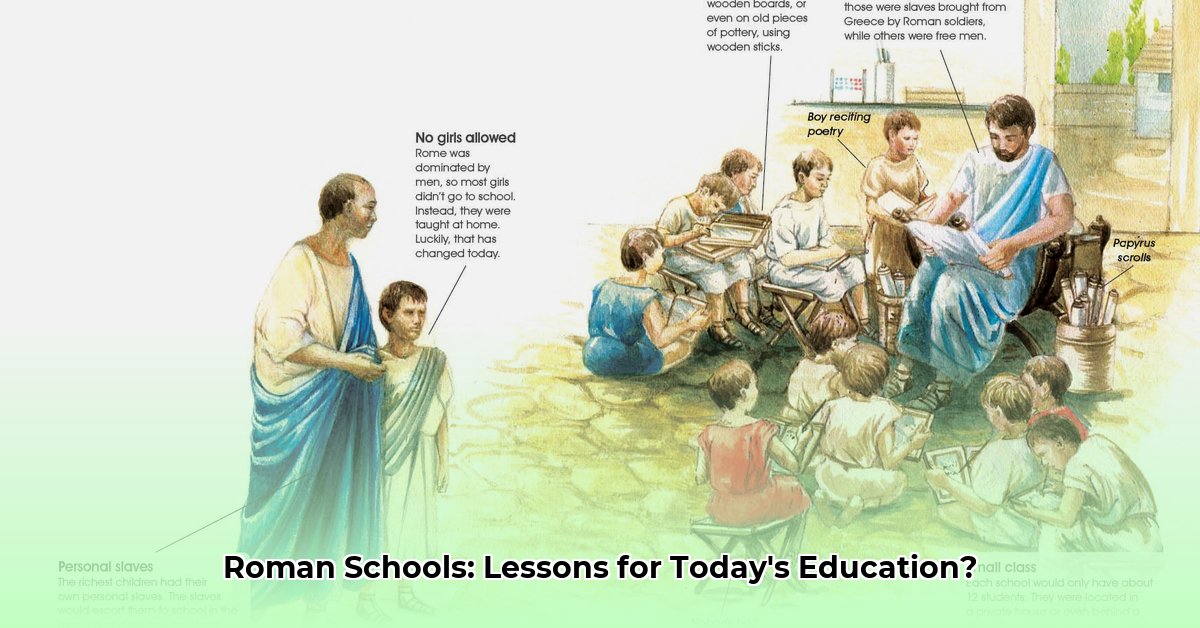

- The Ludus Litterarius (Elementary School): Around the age of seven, children from more affluent families might attend a ludus litterarius, literally “school of letters.” Here, under the guidance of a litterator or magister, students diligently learned foundational skills. Lessons began at dawn and concluded by noon, often held in rented rooms, shop annexes called pergulae, or even in bustling public spaces like street corners (trivium), as famously lamented by the poet Martial for their noise. Students learned to form and write letters by tracing them carved into wooden boards. They then progressed to syllables, words, and simple sentences, meticulously copying texts onto small waxed tablets using a stylus, or occasionally on expensive papyrus or broken pottery pieces (ostraca). Basic arithmetic began with counting on fingers and pebbles (calculi), advancing to the abacus, with addition and multiplication often learned through chanting. The curriculum frequently incorporated moral sayings, ensuring that literacy practice also instilled Roman values. Learning was highly individualized, with students working independently and approaching the teacher for instruction and corrections. There were no formal exams; performance was judged on the spot.

- Grammar Schools (Secondary Education): Typically beginning between the ages of ten and twelve, entry to grammar schools, led by a grammaticus, was largely reserved for the wealthy elite. The word grammaticus denoted a teacher who guided students through more advanced studies in both Latin and Greek literature. The curriculum delved deeply into classical texts, dissecting the works of authors like Homer, Hesiod, Euripides, Virgil, and Livy. Students refined their grammar, explored elements of poetry, history, and mythology, and sharpened their critical thinking through detailed textual analysis (partitio). Daily activities included lectures (narratio) and expressive reading (lectio). The curriculum was thoroughly bilingual, expecting students to read and speak proficiently in both Greek and Latin. Famous grammatici included Lucius Orbilius Pupillus, known for his stern discipline, and Marcus Verrius Flaccus, who pioneered competitive learning by offering prizes for student achievement. These schools nurtured refined minds capable of intellectual discourse.

- Rhetoric Schools (Advanced Training): For elite young men, typically from sixteen years old and sometimes extending into their early twenties, the pinnacle of Roman education was rhetoric school. Guided by a rhetor, these aspiring orators honed the art of public speaking—a skill paramount for careers in law, politics, and the military throughout Roman history. Students engaged extensively in declamation, practicing speeches on invented legal or political cases. Two common exercises were the suasoria (a fictitious speech advising a historical figure on a course of action) and the controversia (arguing one side of a point of law). These exercises, as recorded by Seneca the Elder, not only built speaking skills but also reinforced the views of the Roman elite. The curriculum was broad, encompassing Roman law, history, philosophy, geography, literature, and mythology, providing a comprehensive education for future leaders. While early rhetoric was learned through observation, it later became a formal institution. Tacitus noted a shift in the 1st century AD, with declamation focusing more on delivery than on critical legal issues. Due to their immense influence, rhetoricians and philosophers were sometimes viewed with suspicion by the Roman government, leading to expulsions in times of political upheaval.

- Philosophical Study: The final, most elite level of education was philosophical study, distinctively Greek in origin but pursued by many wealthy Romans. To engage in deep philosophical study, a student typically traveled abroad to centers of philosophy in Greece. While Roman society focused its educational efforts on developing schools of law and rhetoric, philosophical understanding was considered the highest intellectual pursuit and contributed significantly to the vast knowledge base of figures like Cicero. Access to such advanced study was limited to the very wealthiest of Rome’s elite.

Throughout these stages, a paedagogus—often an enslaved attendant of Greek origin—might accompany a boy to school, assisting with studies and ensuring discipline. While the concept of using enslaved individuals is ethically problematic by modern standards, the paedagogus offered a form of personalized oversight, a precursor to modern private tutoring.

A System of Disparity: Access, Limitations, and Pedagogy

Despite its structured progression, the Roman educational system was far from equitable. Rome never formally instituted a state-sponsored system of elementary education, and it never legally required its citizens to be educated. Access to quality, advanced schooling was largely determined by wealth and social status, creating a significant divide. Poorer children often had limited, if any, formal schooling, frequently entering the workforce at a young age after acquiring only basic literacy for practical purposes.

Education for Roman Girls: A Distinct Path

The question of how did Roman girls learn reveals another layer of societal disparity. While formalized public education, particularly at the advanced levels, was predominantly for boys destined for public life, girls, especially from affluent families, were not entirely excluded from learning. For girls from prosperous families, basic education in reading, writing, and rudimentary arithmetic often occurred privately at home with tutors, or sometimes in ludi litterarii. However, their schooling was primarily geared towards domesticity and preparing for marriage. Didactic lessons in household management, virtue, social graces, and practical skills like spinning, weaving, and music formed the core of their curriculum.

Early marriage, often in their early teens, frequently curtailed girls’ formal studies compared to their male counterparts. Yet, for some elite women, intellectual pursuits continued privately, venturing into literature and philosophy. This intellectual engagement, though often confined to the domestic sphere, provided significant social and intellectual avenues. The philosophical currents of the time, championed by Stoic thinkers like Musonius Rufus, who advocated for equal education for both sexes, challenged prevailing Roman norms by arguing that reason and virtue were universal and equally necessary for both men and women. However, the extent to which these progressive ideas translated into widespread change in women’s educational experiences remains a subject of nuanced historical debate. Slave children, if educated at all, learned skills directly relevant to their masters’ needs, such as accounting or specific trades.

Beyond the socioeconomic and gender inequities, the Roman system also relied heavily on rote learning and strict discipline. Learning was achieved through repetitive memorization of texts and rules until they were ingrained. Teachers did not teach the class as a whole; students worked individually and recited lessons to the teacher. Physical punishment, like the use of the ferula rod or whipping (as noted for Orbilius Pupillus), was an accepted and common disciplinary tool, often welcomed by fathers who expected prompt progress. This approach, while effective for instilling facts and obedience, might have stifled individual creativity and independent critical thinking in the modern sense. Competition was also a key motivator, with teachers like Verrius Flaccus using prizes to spur students.

Ancient Lessons for Modern Classrooms: Actionable Takeaways

The enduring legacy of ancient Roman schools continues to offer invaluable insights for contemporary educational systems. By critically examining both the strengths and weaknesses of this historical model, we can draw crucial lessons for addressing modern challenges and fostering more effective, equitable learning environments.

Here are actionable strategies for various stakeholders:

-

For Curriculum Creators:

- Short-Term (0-1 Year): Integrate core Roman values of civic duty, ethics, and pietas (devotion to responsibility) into modern curricula, particularly in civics and social studies, to foster responsible and engaged citizens.

- Long-Term (3-5 Years): Explore the benefits of multi-tiered educational systems, adapting the Roman model to contemporary needs. Simultaneously, actively work to ensure genuinely equal access and opportunities for all students at every level, systematically addressing historical and ongoing socioeconomic disparities in education.

-

For Policymakers:

- Short-Term (0-1 Year): Investigate the contemporary relevance and potential benefits of greater family involvement in early childhood education, drawing inspiration from the proactive pater familias model in developing foundational moral and practical skills.

- Long-Term (3-5 Years): Reflect on the broad societal benefits of emphasizing practical skills, robust civic education, and persuasive communication alongside theoretical knowledge. This holistic approach aims for well-rounded graduates prepared for both professional careers and active community roles, fostering resilient societies.

-

For Historians/Researchers:

- Short-Term (0-1 Year): Re-evaluate existing historical sources more critically to uncover and highlight subtle or previously overlooked evidence of female education across different social strata in ancient Rome, moving beyond traditional narratives.

- Long-Term (3-5 Years): Systematically integrate a comprehensive gendered lens when analyzing Roman social structures, intellectual history, and educational practices to create a more nuanced, inclusive, and accurate historical narrative that acknowledges diverse experiences.

-

For Educators:

- Short-Term (0-1 Year): Incorporate elements of classical rhetoric into public speaking, debate, and argumentation courses to promote clear, persuasive communication and critical analysis of information. Additionally, facilitate classroom discussions on the historical context of gendered education disparities and socioeconomic barriers to foster critical thinking about equity and access in modern educational contexts, connecting the past to present realities.

- Long-Term (3-5 Years): Promote awareness among students regarding women’s historical and ongoing intellectual contributions across various fields, even in societies where their opportunities were historically limited. This can foster a broader appreciation of human potential and challenge contemporary biases.

-

For Museums/Cultural Institutions:

- Short-Term (0-1 Year): Develop compelling and sensitive exhibits and digital resources that specifically highlight the diverse experiences of educated women in ancient Rome, challenging simplistic or one-dimensional portrayals.

- Long-Term (3-5 Years): Create accessible educational programs and interactive multimedia resources that actively challenge common misconceptions about women’s and marginalized groups’ roles in ancient societies, offering a more nuanced and accurate portrayal of their intellectual lives, daily experiences, and contributions.

The Greek and Roman influences in ancient education systems laid fundamental groundwork for many structures we recognize today, from multi-stage learning to the emphasis on communication and civic duty. By critically examining their past—particularly the successes of their structured curricula, the realities of their pedagogical methods, and the stark realities of their social inequalities—we gain invaluable perspectives for shaping a more effective and equitable future in education. The historical journey from ludus to rhetoric informs our present, reminding us that education is perpetually in dialogue with its societal context, striving for an ideal that profoundly bridges knowledge with character.