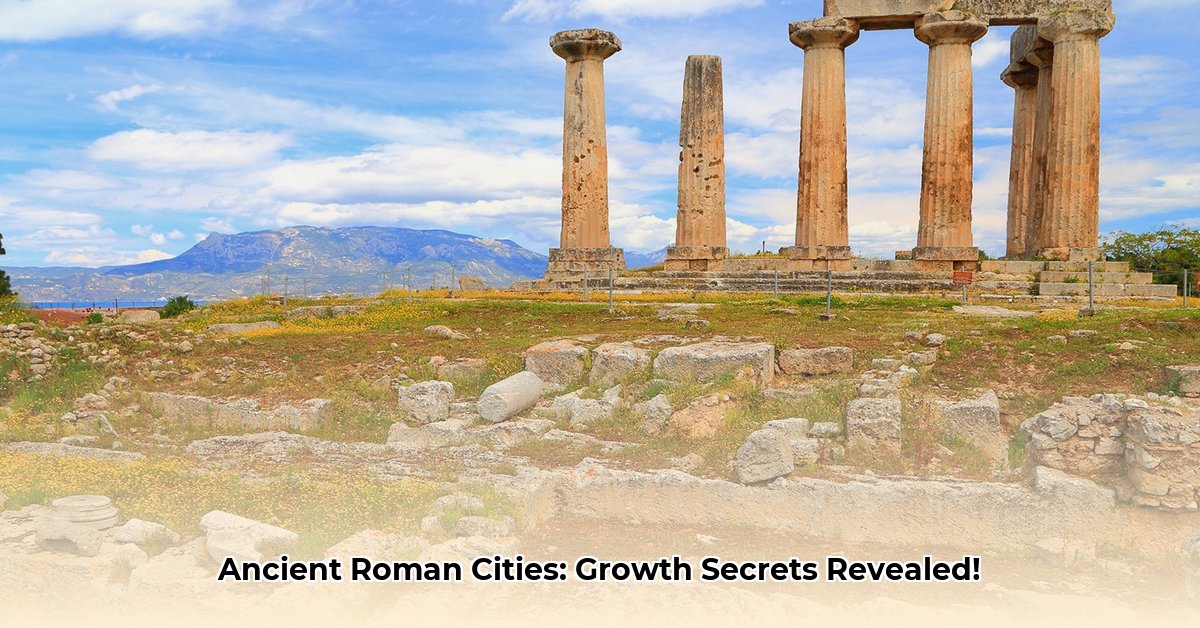

Ever wondered how a vast civilization like the Roman Empire sustained its monumental scale and enduring influence for centuries? Beyond its famed legions and political machinations, the true genius of Rome often lay in its profound mastery of urban planning and development. Roman cities were not merely clusters of dwellings; they were meticulously engineered powerhouses, serving as dynamic engines of trade, governance, military projection, and cultural assimilation across an expansive domain. From their bustling forums and advanced infrastructure to their strategic locations, these urban centers comprised complex systems that both sustained and expanded imperial authority. This article delves into the foundational principles of Roman urbanism, explores how these cities adapted and thrived across diverse conquered territories, examines the subtle yet significant shifts that led to their eventual decline, and crucially, reflects on the timeless lessons they offer for contemporary urban planning and societal resilience. You can read more about this at ancient Roman cities.

At their core, ancient Roman Empire cities transcended simple population centers; they functioned as vital arteries of the empire, evolving from humble military outposts into sophisticated hubs of power, innovation, and cultural synthesis. Their unparalleled success hinged on a remarkable precision in urban planning, exemplified by highly organized grid layouts, centrally located forums, and engineering marvels such as vast aqueducts and an extensive network of roads. This systematic approach allowed for extraordinary adaptability, as the Romans adeptly integrated existing settlements into their framework or engineered entirely new cities, a dynamic process vividly highlighted by the pivotal East-West shift of imperial power and the rise of new economic and political strongholds.

The Unseen Pillars of Empire: Why Roman Urbanism Mattered

Roman cities formed the indispensable bedrock of imperial stability and sustained growth. Initially, many of these settlements began as strategic colonies (coloniae), purpose-built to house retired legionaries or Roman citizens and serve as military garrisons. These nascent settlements rapidly transformed, blossoming into critical centers for both commerce and cultural exchange. They functioned as powerful anchors, securing newly conquered territories and projecting Roman authority far and wide, effectively integrating diverse regions into the cohesive imperial structure. This comprehensive urban network facilitated the efficient collection of resources, dissemination of Roman law, and rapid movement of troops, making them indispensable to the empire’s vast and widespread influence.

Engineering Grandeur: The Roman Urban Blueprint Unveiled

The genius of Roman urban planning is unequivocally demonstrated in its thoughtful, highly structured, and remarkably consistent approach. Most Roman cities, particularly those founded anew, adopted a highly efficient and standardized grid pattern, uniformly bisected by two major thoroughfares: the Cardo Maximus, predominantly running north-south, and the Decumanus Maximus, extending east-west. These principal roads typically intersected at the Forum, which served as the city’s pulsating heart. This central civic space hosted essential administrative functions, religious ceremonies dedicated to the Roman pantheon, vibrant public markets, and crucial meeting places, providing a cohesive and accessible core for civic life. Imagine the remarkable efficiency and order of a society operating within such a meticulously organized urban framework, designed for maximum operational harmony and control.

One of the most striking hallmarks of ancient Roman Empire cities was their cutting-edge infrastructure, a testament to Roman engineering prowess. These metropolises boasted meticulously constructed roads, forming an astonishing 400,000-kilometer (approximately 250,000-mile) network across the empire. These roads were crucial for facilitating rapid trade, efficient communication, and swift troop movements, effectively binding distant lands to Rome. Beyond roads, advanced aqueducts, such as the famous Pont du Gard in southern France, delivered fresh, clean water from distant sources to urban inhabitants for public baths, fountains, and private homes. Sophisticated sewer systems, exemplified by Rome’s Cloaca Maxima, were vital for maintaining public health and sanitation. Robust defensive walls, often studded with imposing gates, offered crucial protection against external threats, transforming cities into formidable strongholds. These extraordinary feats of engineering unequivocally showcase the unparalleled skill and ingenuity of the Roman people, a remarkable legacy of innovation that continues to captivate and instruct us today.

Public spaces were also central to Roman urban design. Grand amphitheaters, like the iconic Colosseum, hosted spectacular gladiatorial contests and public spectacles, serving as centers of mass entertainment and social cohesion. Expansive public baths were not merely places for hygiene but vibrant social and recreational hubs, offering hot and cold pools, saunas, and massage rooms, fostering community interaction. Temples dedicated to various gods and goddesses were prominent architectural features, reflecting the integral role of religion in daily life. Theatres and odeons provided venues for plays and musical performances, showcasing Roman culture and arts. Even housing varied greatly, from luxurious villas for the wealthy elite to crowded multi-story insulae (apartment buildings) for the poorer citizens, reflecting the social stratification within these bustling urban centers.

A Tale of Two Approaches: Adapting & Creating Urban Centers

So, how did Roman cities adapt to conquered territories and integrate diverse populations? The answer lies in a pragmatic blend of integration and strategic development. The Romans frequently incorporated or subtly adapted existing urban centers following conquests, leveraging their pre-existing infrastructure and populations. Consider the historical cities of Athens, famed for its profound intellectual heritage and existing democratic traditions, or Jerusalem, a site of immense religious significance and a deep-rooted historical identity. In these cases, Roman administration overlaid existing structures, maintaining a degree of local continuity while asserting imperial control.

In other instances, particularly in frontier regions or strategically vital locations, the Romans demonstrated their visionary planning by constructing entirely new cities (coloniae) from the ground up, designed precisely to Roman specifications. A prime example is Timgad (Thamugadi) in modern-day Algeria, founded by Emperor Trajan around 100 CE as a military colony for retired soldiers. Its perfectly orthogonal grid layout, complete with Cardo and Decumanus, forum, baths, and theater, remains a pristine example of Roman urban planning imposed upon a new landscape. Another monumental example is Constantinople, now Istanbul, which was built from scratch on the site of the older Greek city of Byzantium, becoming a “New Rome.” This dual strategy remarkably highlights the Roman capacity to both integrate diverse existing cultures and forge entirely new centers of imperial power, effectively disseminating Roman values and authority.

The uniformity observed across many Roman cities wasn’t merely coincidental; it was a deliberate projection of imperial power and order. Roman urban planning prioritized military and administrative efficiency. The characteristic orthogonal grid layout facilitated the swift deployment of troops and effective oversight, thus projecting an undeniable image of imperial order and control. Beyond the military, this order was also projected through civilian institutions. The Romans understood that genuine integration of conquered peoples was as crucial as military victory. They established coloniae (colonies) as strategic outposts, frequently settled by Roman veterans, such as Colonia Ulpia Traiana (modern Xanten) in Germania. These colonies served as miniature Romes, actively disseminating Roman culture, language (Latin), and institutions. Concurrently, municipia were communities that progressively gained Roman citizenship, thereby integrating their populations directly into the sophisticated Roman political and legal system. This inclusive approach was key to long-term stability and imperial cohesion.

While Roman expansion brought significant advancements in infrastructure, law, and administrative efficiency, it also cast a considerable shadow. Although the elite often reaped substantial benefits from enhanced access to resources, expanded trade networks, and new administrative roles, ordinary citizens frequently contended with economic exploitation and deep-seated social inequality. The widespread reliance on chattel slave labor, acquired through conquest and trade, was a pervasive issue, contributing to social tensions and considerably limiting opportunities for free citizens. The prosperity brought by Roman rule was, sadly, not universally shared, and the imposition of Roman order often came at the cost of local autonomy and cultural practices.

The Eastern Shift: Constantinople’s Rise and Enduring Legacy

The rise of Constantinople as the “New Rome” marks a profound and pivotal redistribution of political and economic power within the empire. Founded by Emperor Constantine in 330 CE on the strategic site of ancient Byzantium, this new capital was conceived as a testament to Christian Rome and a reflection of the empire’s shifting geopolitical weight. Following the Western Roman Empire’s eventual collapse in 476 CE, the Eastern Roman Empire, with its formidable capital in Constantinople, emerged as the dominant political, economic, and cultural force. This transition was a watershed moment in Roman history, as the Eastern Empire, later known as the Byzantine Empire, continued to flourish for an astonishing thousand years after the decline of its Western counterpart, meticulously preserving and evolving Roman traditions, laws, and culture.

The fracturing of the Roman Empire was not an abrupt cataclysm but a protracted, gradual process driven by a confluence of factors. Its sheer, unwieldy size posed immense administrative challenges, akin to managing a vast multinational corporation with rudimentary communication technologies. Internal strife and persistent political instability exacerbated these difficulties; the 3rd century CE, for instance, witnessed near-constant civil wars and rapid successions of emperors, weakening the central authority. Emperor Diocletian’s well-intentioned but ultimately temporary division of the empire into East and West (the Tetrarchy) inadvertently laid the groundwork for a permanent split by formalizing distinct administrative spheres.

The economic disparity between the Empire’s eastern and western halves was striking. The Eastern provinces, blessed with bustling cities like Alexandria (a beacon of knowledge and trade), Antioch (the “Queen of the East,” a vital hub on the Silk Road), and especially Constantinople, thrived dynamically due to robust trade networks, fertile agricultural lands, and a more diversified economy. In contrast, the West frequently struggled with economic stagnation, diminishing resources, and a less developed urban infrastructure. This stark economic contrast undeniably fueled the growing divide, as the East’s inherent wealth and stronger urban centers naturally drew power and influence.

Relentless external threats, particularly the escalating barbarian invasions (Goths, Vandals, Huns), profoundly battered the empire. The Western half, already weaker and more resource-deprived, largely crumbled under this sustained pressure, culminating in the sack of Rome in 410 CE and the deposition of the last Western Emperor in 476 CE. In stark contrast, the East proved significantly more resilient, fortified by its economic vitality, stronger military, and formidable strategic defenses, notably Constantinople’s impenetrable Walls of Theodosius.

Divergent cultural identities further widened the chasm between East and West. The West steadfastly adhered to Latin language and traditional Roman customs, while the East embraced Greek language and Hellenistic culture, which had long been dominant in the region. These accumulating differences fostered a growing sense of distinct identity, cementing the eventual separation, even as both halves claimed the mantle of “Roman.”

Emperor Constantine’s momentous decision in 330 CE to relocate the imperial capital to Constantinople irrevocably shifted the empire’s geopolitical focus eastward. This move, driven by the East’s pre-existing economic and strategic strengths, left the already struggling West feeling increasingly marginalized and neglected. The Eastern half now undeniably became the favored and more dominant half of the empire, inheriting many of Rome’s traditions and evolving them into the unique Byzantine civilization.

The formal and definitive political split occurred in 395 CE when Emperor Theodosius I divided the empire between his two sons, Arcadius receiving the East and Honorius the West. From this point forward, the Eastern and Western Roman Empires functioned as entirely separate political entities, each possessing its own distinct leadership, governmental structure, and military forces. The two halves embarked on fundamentally different historical trajectories, one towards collapse and fragmentation, the other towards a millennium of continued imperial rule.

This profound division of the Roman Empire fundamentally reshaped the future of both Europe and the Mediterranean basin. It gave rise to the development of distinct civilizations and enduring traditions, influencing everything from legal systems and languages to architectural styles (e.g., Byzantine art vs. early medieval Western art) and political thought. This monumental schism has left a legacy that continues to resonate and shape the modern world, especially through the distinct development of Western and Eastern Europe.

The East-West split also carried monumental religious implications. In the West, the Christian Church evolved into the Roman Catholic Church, centered in Rome and led by the Pope. Simultaneously, in the East, the Christian Church developed into the Eastern Orthodox Church, with its spiritual heart in Constantinople. Deep-seated disagreements over theological doctrine (e.g., the Filioque clause), liturgical practices, language, and ultimately, ecclesiastical authority, culminated in the Great Schism of 1054, formally dividing Christianity into these two major branches. This historic division, originating from the broader imperial separation, endures to this very day, shaping global religious landscapes.

The fragmentation of the Roman Empire was not a singular event but a complex interplay of long-term trends, significant economic imbalances, profound cultural differences, and unrelenting external pressures. Understanding these multifaceted factors offers critical insights into how vast entities can fragment and, crucially, how societies can endeavor to construct more resilient and equitable systems for the future.

Consider this table illustrating the key differences that solidified the East-West divide:

| Feature | Western Roman Empire | Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantine Empire) |

|---|---|---|

| Economy | Declining, agrarian, less urban | Thriving, vibrant trade-based, highly urbanized |

| Dominant Culture/Language | Latin-based, more traditional Roman | Greek-based, Hellenistic influence predominant |

| Political Stability | Highly unstable, frequent civil wars | Relatively stable, strong centralized imperial rule |

| Resilience to Invasions | Weak, highly susceptible, ultimate collapse | Strong, often repelling invasions, long-lasting |

| Dominant Christian Branch | Roman Catholicism (centered in Rome) | Eastern Orthodoxy (centered in Constantinople) |

| Capital City | Rome, then Ravenna/Mediolanum | Constantinople |

The Gradual Dusk: Unpacking the Decline of Roman Cities

The decline of Roman cities, particularly in the Western Empire, didn’t occur as a sudden, cataclysmic event, but rather as a drawn-out, gradual process spanning centuries. It was a multifaceted unraveling, influenced by a complex convergence of economic woes, persistent political instability, and relentless external pressures. Environmental shifts and critical administrative challenges further compounded these difficulties. Crucially, the impact of this decline varied significantly across different regions, with some cities exhibiting remarkable resilience compared to others, while frontier cities experienced more rapid and severe contractions. Understanding these complex factors offers invaluable insights, even for contemporary urban planning.

Economic Instability and Urban Decay

The once-robust economic foundations of Roman cities began to progressively erode, particularly from the 3rd century CE onwards. Disruptions to established long-distance trade routes, exacerbated by civil wars and barbarian incursions, severely hampered commerce. Widespread inflation, debasement of currency, and heavy taxation steadily eroded purchasing power across the empire, leading to a decline in internal markets. Consequently, urban areas, which thrived on vigorous economic activity facilitated by trade and manufacturing, suffered immensely as resources became scarce, public works dwindled, and opportunities for commerce diminished. This relentless financial strain was a central catalyst in the slow decline of many once-flourishing metropolises, forcing populations to seek subsistence in rural areas.

Political Turmoil and Governance Breakdown

Political stability is an indispensable prerequisite for any thriving urban society. Unfortunately, the late Roman Empire was plagued by protracted periods of weak leadership, frequent and devastating civil wars (e.g., the Crisis of the Third Century), and pervasive, systemic corruption within the imperial administration. The repercussions of these profound political issues were especially acute within urban centers. The absence of effective, trustworthy governance systematically undermined civic trust, critically hindering the provision of essential public services like water supply and sanitation, and crucially impeding the maintenance of vital infrastructure such as roads, aqueducts, and public buildings. This relentless erosion of political order was a fatal blow to the quality and sustainability of urban life, leading to depopulation and abandonment.

External Invasions and Security Concerns

Once seemingly invincible, the Roman Empire faced continuous and escalating external threats, particularly from migrating “barbarian” tribes such as the Goths, Vandals, and Huns. Relentless invasions placed cities under immense, almost unbearable pressure. Precious resources, once allocated to urban development and amenities, were increasingly diverted to defense efforts, leading to neglected infrastructure and reduced public services. The constant specter of insecurity led to a sharp decline in trade and migration, as people sought safety in fortified rural strongholds rather than vulnerable urban centers. Cities like Londinium (Roman London) faced periods of abandonment or severe contraction due to raids and insecurity, further weakening their economic and social fabric. These incessant external pressures were indeed a decisive factor in the decline and transformation of many Roman urban centers.

Environmental Shifts and Resource Depletion

Environmental changes also exerted a considerable, often overlooked, impact on Roman cities. Pervasive resource depletion, including widespread deforestation for construction and fuel, and significant soil erosion from intensive agriculture, placed immense strain on urban populations already struggling with other challenges. The silting of harbors, as seen in Ephesus, gradually rendered once-vital port cities obsolete, severing their economic lifelines. Additionally, the potential effects of climate change, specifically a period of cooling and increased aridity known as the Late Antique Little Ice Age, may have triggered agricultural decline, reduced crop yields, and subsequent population displacement, further contributing to urban distress. How precisely did these subtle environmental factors undermine the long-term sustainability and viability of Roman cities?

Administrative Challenges and Civic Neglect

Effective administration forms the bedrock of any functioning city. Regrettably, Roman cities increasingly grappled with severe administrative dysfunction. Pervasive corruption, rampant inefficiency, and a critical lack of resources systematically hampered sound urban management. Local elites, who once heavily invested in public works (evergetism), began to retreat from civic responsibilities due to economic hardship and the increasing burden of imperial taxes. As a direct consequence, vital public services plummeted, and essential infrastructure deteriorated alarmingly. Cities, once vibrant and well-maintained, struggled profoundly to provide adequately for their inhabitants, leading to a vicious cycle of decline. This chronic civic neglect was a major internal cause of the decay of Roman urban centers.