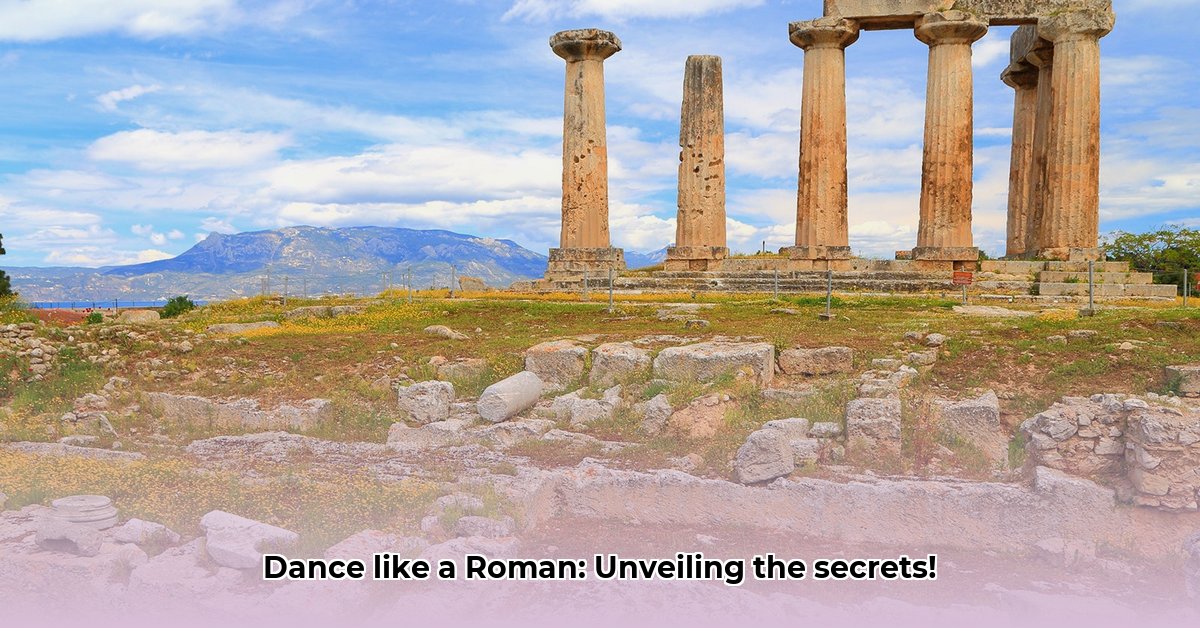

The story of ancient Roman dance offers a captivating glimpse into their evolving culture. Far from being a mere pastime, physical expression through movement was deeply woven into the fabric of daily life, transitioning from solemn religious rituals to grand theatrical spectacles. This transformation vividly reflects Rome’s extensive cultural absorption, particularly from the sophisticated Etruscans and the artistically advanced Greeks. Learn more about Roman entertainment. How did this art form, steeped in tradition, evolve from vital sacred ceremonies to captivate emperors and stir profound moral debate within the very heart of the Republic and Empire?

Early Rhythms: Etruscan Echoes and Native Forms

Before Rome became a dominant power, the Italian peninsula vibrated with diverse cultural expressions. Early Roman dance forms, initially influenced by the mysterious Etruscans, were primarily religious rituals and military exercises. These were not casual movements; practices like the precise, drill-like performances of the Salii priests, dedicated to Mars Gradivus (“Marches Forth to War”), were considered fundamental to the state’s religious life. These armored warriors, established by King Numa, would parade through Rome to the music of trumpets, performing intricate shuffled steps, high leaps, and shield beats to invoke divine favor, believed to secure victory in battle and stability for the Republic. Visual evidence from Etruscan tombs, such as the Tomba dei Cacciatori and Tomba delle leonesse, also depicts vibrant, wild dances—some performed nude, others with minimal clothing—to the sounds of the double-aulos, highlighting an early emphasis on physical expression and festivity.

Romans also developed their own native war dances, like the bellicrepa, supposedly instituted by Rome’s founder, Romulus, and performed by soldiers in battle ranks. These initial rhythms set the stage for dance as a potent form of expression, deeply tied to community welfare, spiritual connection, and martial identity, rather than solely entertainment. The Romans in early times practiced religious dancing, with the processions of the Salii or priests of Mars, and of the Arval Brothers, being the best-known examples of such ritual performances.

The Hellenic Infusion: Greek Influence and Theatrical Ascent

As Rome expanded its dominion, it increasingly absorbed cultural elements from the Greeks and their decadent period, ushering in a significant Greek transformation in Roman dance. The Greeks, renowned for their love of theater, introduced more refined forms such as mime and pantomime. These performances, which saw single actors use masks and expressive gestures to narrate myths, quickly soared in popularity. By the 2nd century BCE, waves of Greek performers, often brought to Rome as slaves and later freed, flooded the city, enriching its theatrical scene. This era saw the emergence of professional dancers and the establishment of dance schools.

However, the increasing popularity of these elaborate shows signaled not only cultural advancement but also a source of moral concern for many Roman traditionalists. Figures like Scipio Aemilianus, a Roman aristocrat, attempted to close down dance schools in the mid-2nd century BCE, viewing expert dancing as a symptom of depravity. Despite this criticism, the public’s appetite for such entertainment only grew, proving dance served as a powerful social mirror, reflecting and sometimes challenging societal values. Performances became increasingly focused on spectacle and physical display, often incorporating burlesque, overtly erotic, comic, and frightening elements, which further fueled moral debates.

Imperial Spectacles: Emperors, Performers, and Patronage

The Imperial era truly cemented dance’s role as a grand spectacle. Emperors like Augustus championed pantomime, and later, Nero, a known enthusiast and even a participant himself, further elevated its status by building permanent theaters, the first of which opened in 55 BCE. This imperial patronage transformed dance into a cornerstone of public entertainment. Pantomime, a uniquely Roman innovation refined by artists like Pylades and Bathyllus around 22 BCE, allowed artists to convey complex narratives entirely through gesture, music, and elaborate costumes, transcending linguistic barriers. Pylades innovated the tragic pantomime with a full orchestra, while Bathyllus favored more joyous performances.

This period saw the rise of celebrity dancers, whose skills were widely admired, prompting specialized schools and rigorous training. Historical accounts reveal their popularity, with Juvenal mentioning “Spanish maidens to win applause by immodest dance and song, sinking down with quivering thighs to the floor,” indicating the highly explicit nature of some performances. These dancers, often slaves from Greece or Spain, could achieve fame and fortune, yet paradoxically, their increasing visibility and allure contributed to a sinking status of dancers. From respected artists in religious roles, they gradually became perceived as low-status professionals, a stark contrast to their earlier sacred functions. The Roman historian Livy noted the introduction of Etruscan dancers to placate a plague in 364 BCE, initially without words or mimetic action, evolving into professional theatrical performances. This complex shift highlights the tension between art, social class, and political power in ancient Rome. Despite the moral controversy and fluctuating public perception, the insatiable Roman demand for lavish visual storytelling ensured dance remained a vibrant and integral part of their public life, accompanied by instruments such as lyres, castanets, tambourines, double-aulos, cymbals, panpipes, and trumpets.

Societal Reflections and Enduring Legacy

The story of dance in ancient Rome is a narrative of constant flux, reflecting the city’s growth, its cultural exchanges, and its internal debates. The evolution from solemn ritual to dramatic public performance reveals how fundamental values shifted over centuries. The Bacchic cult, for instance, involved frenzied dances by maenads, who, according to Euripides, might tear apart animals with bare hands during their ecstatic rituals. This contrast sharply with earlier, more controlled religious dances. Early Christian leaders later condemned dance, particularly its theatrical forms, due to their association with perceived debauchery and pagan rituals, contributing to a decline in its traditional forms as the Empire waned. The empress Theodora, herself a former pantomime dancer from Constantinople in the 6th century CE, vividly illustrates this transition, demonstrating how even in later Christianized Rome, dance retained a powerful, if controversial, social presence.

Ultimately, by examining the distinct types of dance, the societal attitudes toward performers, and the grand settings in which these movements unfolded, we gain a profound appreciation for the complexities of Roman civilization. The core insights from this journey through time reveal:

- Dance in ancient Rome was dynamic, evolving significantly from its Etruscan roots and native influences into diverse forms of entertainment, constantly adapting to cultural shifts.

- It served multifaceted purposes, deeply embedded in religious rituals, social events, and even as a subtle form of political expression and moral commentary.

- The rise of pantomime, heavily influenced by Greek theatrical styles and shaped by imperial patronage, profoundly impacted Roman performance arts, leading to a complex reassessment of dancers’ social status from revered ritualists to professional entertainers, sometimes viewed with disdain.

The legacy of Roman dance, particularly its emphasis on spectacle and gestural storytelling, continues to resonate in contemporary performing arts, from ballet to mime, proving the enduring power of human movement as a means of expression and a mirror to societal values across millennia.