Catholicism, with its rich tapestry of faith and global reach, employs a distinct array of symbols to articulate its foundational beliefs. These elements are far more than mere decoration; they serve as a profound visual shorthand for complex theological concepts, historical narratives, and the Church’s teachings. Consider the universally recognized Cross, an immediate emblem of Jesus’ sacrifice, or the gentle Dove, frequently representing the Holy Spirit. Such symbols are intrinsically woven into Catholic worship, art, and the traditions passed through generations, forming the very iconography of the faith.

Yet, a fascinating complexity arises when probing the origins of these emblems. Do all Catholic symbols share a straightforward, unblemished lineage, or do some carry more intricate histories, perhaps reflecting influences from pre-Christian eras? This inquiry sparks important discussions regarding the provenance of these visual markers and their contemporary understanding within the Church. This article delves into both the sacred origins and the intriguing controversies surrounding these powerful symbols, offering a comprehensive view.

The Enduring Significance of Catholic Symbolism

Catholic symbols are not simply aesthetic additions; they are powerful communicators of faith, history, and theology. They bridge the gap between the earthly and the divine, serving to inspire devotion, provide spiritual guidance, and strengthen communal identity among believers. These profound visual cues convey core beliefs and commemorate pivotal historical events in a tangible and memorable way.

For instance, the Crucifix, an internationally recognized emblem, vividly represents Jesus Christ’s ultimate sacrifice and the promise of human redemption. Similarly, the Ichthys, or fish symbol, functioned as a clandestine sign among early Christians during periods of intense persecution, enabling them to identify fellow believers and express their faith in a covert manner. Each symbol is chosen deliberately, acting as a potent reminder of the faith’s deepest truths.

Foundational Symbols: Scripture and Tradition

Many integral Catholic symbols derive their meaning and form directly from scripture, deeply rooting them in biblical narratives and centuries of sacred tradition.

- The Cross and Crucifix: As principal symbols, the Cross encapsulates Jesus’ death and resurrection, while the Crucifix, featuring Christ’s figure, offers a direct image of this ultimate sacrifice. It stands as a testament to profound love and redemption.

- The Sacred Heart: This image signifies Christ’s boundless love for humanity, often depicted surrounded by a crown of thorns and emitting rays of light, symbolizing His divine compassion and suffering.

- The Lamb of God (Agnus Dei): Representing Jesus as the sacrificial lamb, this symbol highlights His purity and His role in taking away the sins of the world, a theme firmly established in biblical texts (John 1:29).

- Alpha and Omega: As the first and last letters of the Greek alphabet, these symbols signify God’s eternal nature, spanning from the beginning to the end of time, as declared in the Book of Revelation (Revelation 22:13).

- The Chalice: This sacred vessel holds the wine transformed into the Blood of Christ during the Eucharist, symbolizing the new covenant and forgiveness of sins.

- The Paschal Candle: Lit during the Easter season, it represents the Risen Christ, a beacon of hope illuminating triumph over darkness and death.

- Christograms (Chi Rho, IHS, INRI): These abbreviations like the Chi Rho (first two Greek letters of “Christ”) and IHS (first three Greek letters of “Jesus”) are ancient monograms representing Jesus Christ, often found on liturgical items. INRI, seen on crucifixes, translates to “Jesus of Nazareth, the King of the Jews.”

Symbols associated with Mary, the mother of Jesus, also hold immense spiritual weight, embodying purity, humility, and maternal love:

- The Lily and Fleur-de-lis: Both symbolize purity, with the Fleur-de-lis being a stylized lily often associated with the Virgin Mary’s immaculate nature.

- The Letter “M”: A simple yet profound representation of Mary, often seen below the Cross, symbolizing her steadfast presence at Jesus’ crucifixion.

These emblems collectively serve as powerful reminders of faith, hope, and divine love within the Catholic tradition, providing tangible anchors for spiritual contemplation and a deep connection to the divine.

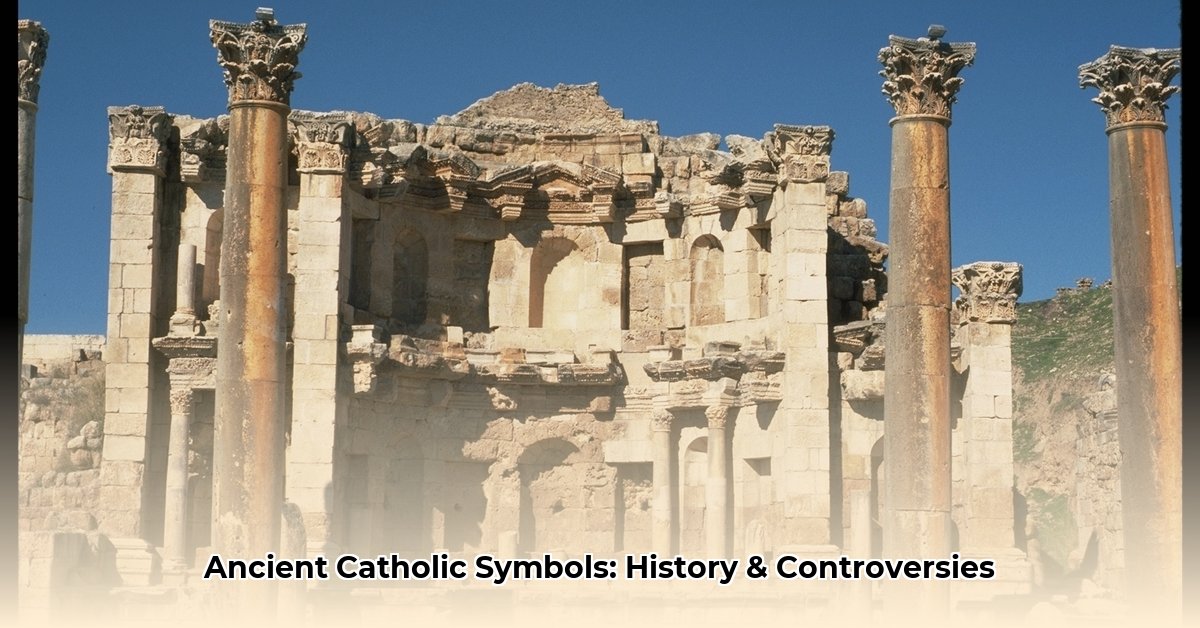

Unraveling Controversies: Pagan Origins and Syncretism

The discussion surrounding Catholic symbols often intensifies when considering claims of pre-Christian or pagan influences. Critics sometimes point to specific symbols, liturgical attire, and even church structures, suggesting they reflect the worship of ancient deities rather than solely the Christian God. This raises a crucial question: is it truly possible that visual elements from older, non-Christian beliefs were either adopted or repurposed within Catholicism? This inquiry prompts a deeper exploration of a nuanced historical process often termed “syncretism” or “cultural assimilation.”

Echoes in Rituals and Vestments

Several elements within Catholic practice have drawn comparisons to ancient pagan iconography:

- The Zucchetti: This small skullcap worn by clergy is sometimes linked by critics to the “Cap of Cybele,” an ancient Anatolian mother goddess whose priests wore similar head coverings. While the Zucchetti’s purpose in Catholicism is distinct—to signify respect and humility—the visual resemblance prompts observers to question its lineage.

- The Mitre: The tall, pointed hat worn by bishops and the Pope is contended by some to resemble the headdress of Dagon, an ancient Philistine fish-god. Historical accounts describe Dagon’s priests wearing a fish-mouth shaped headpiece. Catholic tradition asserts the Mitre’s design evolved independently within early Christian liturgy, symbolizing authority and holiness rather than any pagan deity.

- The Obelisk: The Egyptian obelisk prominently standing in St. Peter’s Square is seen by some as an homage to the ancient Egyptian Sun God, Ra, noting its original placement in front of a temple dedicated to Ra and its alignment with solstices and equinoxes. The Church, however, views its presence as a historical