Ever wondered about the daily lives, deepest beliefs, and visual narratives of ancient Romans? Beyond the famed marble statues and monumental architecture, Roman paintings offer an exceptionally vibrant and intimate window into their world. These aren’t merely decorative pieces; they function as invaluable time capsules, revealing Roman activities, values, and aspirations with astonishing immediacy. Roman artists masterfully blended influences from Greek, Etruscan, and Egyptian art, forging a distinctive style characterized by both practicality and profound aesthetic ambition. From sprawling wall narratives to intimate panel portraits and intricate mosaics, these artworks illustrate how artists employed paint and tesserae (small, meticulously crafted pieces used in mosaics) to shape history, project Roman authority, and create masterpieces that continue to astound us today. See more about Roman Art for visual examples. Furthermore, understanding these treasures highlights the dedicated efforts of archaeologists, art historians, and conservationists in preserving these ancient legacies for future generations.

Ancient Roman Art Paintings: A Journey Through Time and Color

Roman artistry, while drawing significant inspiration from earlier civilizations, evolved into something profoundly unique. More than simple embellishments, it served as a potent instrument for chronicling history, immortalizing emperors, reflecting societal values, and defining cultural identity across a vast empire. While grand sculptures and colossal structures often dominate the popular narrative, let’s explore the captivating and often fragile realm of ancient Roman art paintings.

Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Moment Frozen in Time

The catastrophic eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD inadvertently became a remarkable preservation event. Buried beneath layers of ash and pumice, the cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum transformed into unparalleled time capsules, safeguarding invaluable insights into Roman citizens’ daily lives, including their stunning wall paintings. Remarkably, an estimated 20,000 square meters of painted surfaces have been uncovered from Pompeii alone.

Imagine stepping into a typical Roman home, its walls adorned with vivid frescoes (paintings done directly on wet plaster, allowing the pigments to become an integral part of the wall surface) depicting scenes from everyday life, rich mythology, detailed landscapes, or intricate decorative patterns. These vibrant artworks were more than mere splashes of color; they were direct windows into the Roman psyche, aspirations, and understanding of the world.

The frescoes discovered in the Villa of Mysteries in Pompeii, for instance, are among the most famous. These symbolically rich scenes, depicting human-sized figures engaged in what are believed to be initiation rites associated with the Dionysian mysteries, retain an astonishing vibrancy, appearing almost as if painted yesterday. This offers a powerful testament to Roman artistic skill. What technical mastery do these paintings exhibit? They reveal a profound understanding of techniques like trompe-l’œil (French for “deceive the eye”), where artists skillfully created convincing illusions of depth and realism, tricking the viewer into perceiving three-dimensional scenes on flat walls. In the House of the Vettii, also in Pompeii, mythological friezes and playful Cupid figures adorn nearly every surface, showcasing the Roman penchant for integrating art seamlessly into domestic life. The vivid hues used, often derived from natural earth pigments and costly minerals, speak volumes about Roman aesthetics and their appreciation for rich, integrated color, suggesting a profound societal value for beauty embedded within living environments.

Scholars categorize Pompeian wall paintings into four distinct styles, reflecting a chronological evolution of artistic trends from the 2nd century BCE to 79 AD:

- First Style (Incrustation Style): Characterized by the imitation of colorful marble blocks in stucco, creating a sense of luxury and solidity without actual expensive materials.

- Second Style (Architectural Style): Marked by the illusion of open windows and vast, elaborate landscapes or architectural vistas that extend beyond the actual wall, creating a sense of boundless space.

- Third Style (Ornate Style): A shift towards delicate, monochromatic backgrounds featuring small, central mythological scenes or landscapes, often framed by slender columns and elegant, stylized ornamentation.

- Fourth Style (Intricate Style): A grand, eclectic synthesis combining elements of all previous styles, often featuring large mythological panels, theatrical masks, intricate architectural elements, and vibrant, crowded compositions, creating a dynamic and visually complex effect.

Faiyum Portraits: Faces from the Past

Our journey shifts to Roman Egypt, where a fascinating cultural amalgamation led to the creation of the Faiyum portraits, primarily from the 1st to 3rd centuries CE. These remarkably lifelike paintings, executed on thin wooden panels using encaustic (pigments mixed with heated beeswax) or tempera, were typically affixed to mummified remains, covering the face of the deceased. Unlike the stylized, often generic depictions common in traditional Egyptian funerary art, Faiyum portraits offer individualized and strikingly realistic portrayals of the deceased, providing a tangible sense of their unique features and personalities, from their hairstyles to their jewelry.

These are not merely artistic representations; they are invaluable historical records, offering a direct, almost photographic connection to the faces of people who lived over two millennia ago. Over 1,100 Faiyum portraits have been discovered, making them the largest surviving corpus of painted portraits from antiquity. The survival of these delicate portraits, with their vibrant colors and remarkable detail, is a testament to both the artists’ skill and the unique arid environmental conditions that preserved them within Egyptian tombs. The Faiyum portraits represent a compelling synthesis of Roman realism and Egyptian funerary traditions, illustrating the cultural exchange within the vast Roman Empire. The Roman influence is evident in the naturalistic style of the paintings, while the Egyptian tradition is reflected in their placement on mummies, solidifying their role as a powerful and personal link to individuals from the distant past.

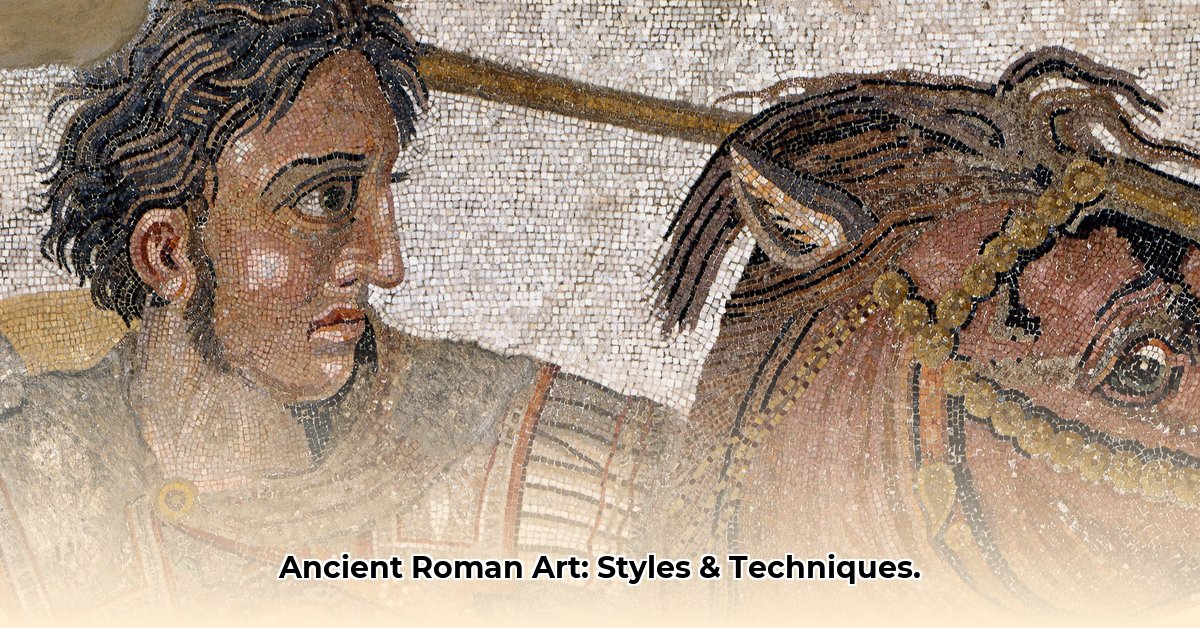

Mosaics: Painting with Stone

While not strictly paintings in the conventional sense, Roman mosaics hold a significant and often overlooked place in any discussion of Roman visual art. These intricate artworks, meticulously fashioned from countless small pieces of colored stone, glass, ceramic, or shells called tesserae, exemplify Roman ingenuity and artistic prowess. They are, in essence, “paintings with stone,” designed for remarkable durability and visual impact.

From elaborate floor mosaics depicting mythological narratives, gladiatorial contests, or scenes of daily life, to simpler geometric designs, mosaics embellished homes, bathhouses, public buildings, temples, and even military structures throughout the vast Roman Empire. Imagine the immense dedication and skill required to create these durable and decorative surfaces, where a single square meter could contain tens of thousands of individual tesserae. They served as a long-lasting and often grand form of “painting,” designed to impress, inspire awe, and reflect the wealth and taste of their patrons. These stunning visual displays indicate that Romans sought to beautify their surroundings through means beyond just traditional fresco, often using mosaics where durability and resistance to foot traffic were paramount.

Consider the famous Alexander Mosaic from the House of the Faun in Pompeii, an incredibly detailed and dynamic scene (measuring 5.82 by 3.13 meters) portraying a dramatic battle between Alexander the Great and Darius III of Persia. This masterpiece, believed to be a copy of a lost Greek painting, demonstrates incredible skill in rendering foreshortening, chiaroscuro (light and shadow), and capturing facial expressions. Another remarkable example is the mosaics from the Villa Romana del Casale in Sicily, a UNESCO World Heritage site, which boasts over 3,500 square meters of floor mosaics, including complex hunting scenes, mythological narratives, and the famous “Bikini Girls.” The intricate level of detail and the dynamic composition of these mosaics are truly breathtaking, showcasing the exceptional skill and artistry of Roman mosaicists, who could achieve painterly effects through the careful selection and placement of tiny tesserae.

Influence, Innovation, and Ongoing Debate

What insights can we glean from Roman painting as a whole? Roman artists, while deeply drawing inspiration from other cultures, were not mere imitators. They adapted and innovated, forging a unique style that truly reflected their own values, sensibilities, and imperial ambitions, molding elements from Greek idealism, Etruscan earthiness, and Egyptian ritual into something distinctly Roman.

However, certain aspects of Roman painting continue to be subjects of scholarly debate. Questions regarding the precise dating of specific works, their exact regional cultural origins within the vast empire, and the precise extent of Roman reliance on or transformation of Greek precedents consistently spark discussion among art historians. The interpretation of frescoes, such as those in the Villa of Mysteries, also remains an ongoing process, with new theories and perspectives emerging regularly through re-analysis and new archaeological discoveries. Is it not fascinating that despite centuries of study, the world of Roman art is still being actively researched, its fragmented pieces assembled, and its narratives refined?

Here’s a breakdown of common Ancient Roman visual art styles, focusing on those related to “painting”:

| Style | Description | Visual Characteristics & Key Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Pompeian Styles | A chronological classification of four distinct styles of Roman wall painting, primarily found in Pompeii and Herculaneum, spanning from the 2nd century BCE to 79 AD. These styles showcase the evolution of decorative trends and illusionistic techniques within domestic and public spaces. They reveal a changing aesthetic, from emulating expensive materials to creating grand illusionistic spectacles, then to delicate, refined compositions, and finally to a complex, eclectic synthesis. | First Style: Faux marble blocks, often in vibrant colors, created using stucco relief and painted surfaces. Example: House of the Sallust, Pompeii. Second Style: Large-scale mythological or landscape murals, often with architectural vistas designed to open up the wall space. Extensive use of trompe-l’œil to create depth. Example: Villa of the Mysteries, Pompeii; Villa of Livia at Prima Porta. Third Style: Return to flat, monochromatic backgrounds with small, elegant central panels. Emphasis on delicate, linear ornamentation and stylized motifs, often with Egyptianizing elements. Example: House of the Prince of Naples, Pompeii. Fourth Style: A busy, eclectic mix, combining elements from all previous styles, often featuring large mythological panels set against rich, fantastical architectural backdrops, framed by intricate, fantastical elements. Example: House of the Vettii, Pompeii. |

| Faiyum Portraits | Unique, highly realistic panel paintings of the deceased, primarily from Roman Egypt (1st-3rd centuries CE), affixed to mummified bodies. These portraits represent a fusion of Roman naturalism with ancient Egyptian funerary traditions. They provide unparalleled insight into the individualized appearance of people from this era, offering direct visual contact with personal identities. | Lifelike, individualized faces painted with encaustic (wax paint) or tempera on wood, often depicting the deceased with specific hairstyles, jewelry, and clothing, capturing their age and personality. Example: “Portrait of a Man” (currently in the British Museum); “Portrait of Isidora” (J. Paul Getty Museum). |

| Mosaics (Opus Tessellatum & Vermiculatum) | Art made from myriad small tiles (tesserae), meticulously set in mortar to create durable, decorative surfaces for floors, walls, and ceilings. While technically distinct from painting (using stone/glass instead of pigment), mosaics achieved painterly effects through intricate detail and shading. They were widely used to depict mythological scenes, geometric patterns, scenes of daily life, and historical events, often serving as a lavish display of wealth and taste. Opus tessellatum refers to larger tesserae for broader designs, while opus vermiculatum uses very small tesserae (often 1-4mm) for fine, painterly detail, especially in central emblemata (medallions). | Rich, detailed compositions made from colored stone, glass, or ceramic tesserae. Often feature dynamic scenes, intricate patterns, or realistic portraits. Example: Alexander Mosaic from the House of the Faun, Pompeii; Mosaics of the Villa Romana del Casale, Sicily; “Drinking Doves” mosaic by Sosos of Pergamon (Roman copies exist). |

| Catacomb Paintings | Early Christian and Jewish wall paintings found in subterranean catacombs in Rome and elsewhere (3rd-5th centuries CE). These paintings often feature simplified forms and symbolic imagery, depicting biblical narratives, funerary scenes, and allegories, reflecting the nascent religious communities’ beliefs and practices. The style often becomes more schematic and less illusionistic over time. | Direct, often schematic figures and scenes, typically on a plain background, illustrating Old and New Testament stories (e.g., Daniel in the Lions’ Den, Jonah and the Whale, Christ as the Good Shepherd). Example: Catacombs of Priscilla (Capella Greca, Cubiculum of the Veiled Woman), Catacombs of Callixtus, Rome. |

A Lasting Legacy

Ancient Roman art paintings, despite their inherent fragility compared to more robust sculptures and architecture, provide invaluable insights into Roman life, beliefs, and artistic sensibilities. They powerfully demonstrate the Roman talent for adaptation, innovation, and compelling visual storytelling. The echoes of Roman painting continue to resonate today, inspiring contemporary artists and captivating audiences around the world, a testament to the enduring power of art itself.

How to Understand Roman Art: Beyond the Stereotypes

Key Takeaways:

- Roman art is a compelling blend of Greek, Etruscan, and Egyptian influences, fundamentally shaped by Roman pragmatism.

- Romans pioneered revolutionary architectural and engineering techniques, extensively utilizing concrete and transforming urban landscapes.

- Roman art embraced an astonishing variety of media, from monumental sculptures and architecture to intricate mosaics, metalwork, and delicate glass.

- It emphasized realism in portraiture, capturing unique individual traits in stark contrast to idealized Greek forms.

- Crucially, art became accessible to a much wider segment of Roman society, with private patronage flourishing and mass production enabling broader enjoyment.

- Roman art consistently reflected its shifting political landscape, serving both state propaganda and personal expression.

The Allure of Adaptation and Roman Practicality

Roman art, spanning nearly a millennium and stretching across three continents, represents a compelling fusion of cultural influences and groundbreaking innovation. It is often perceived as merely derivative of Greek art, a “copycat” culture lacking originality. However, recent analyses reveal a more fascinating truth: a deeply creative adaptation, an eclectic approach, and profound practical applications that truly define Roman artistic expression. As the Roman poet Horace famously observed, “Greece, the captive, took her savage victor captive.” Romans enthusiastically adopted Greek art, commissioning numerous copies of famous works, which in turn helped preserve them. Yet, these were not simple replicas. Roman artists infused their unique touch, adapting themes to suit Roman tastes and purposes. For instance, a gruesome Greek sculpture of Marsyas being flayed might be reinterpreted and functionally integrated as a knife handle in Rome, showcasing a fascinating example of creative reinterpretation and functional design.

Architectural Marvels and Engineering Prowess

Beyond adapting Greek styles, Roman art truly shines through its innovative architecture and engineering. They pioneered revolutionary city-building techniques, extensively utilizing concrete (a highly durable composite material made from cement, aggregate, and water) to create monumental structures like the Pantheon, the Colosseum, and vast aqueduct systems. These marvels showcased Roman engineering prowess and fundamentally transformed urban landscapes across their sprawling empire. To truly understand Roman art in its full scope, one must recognize how the development of the arch, the dome, and concrete construction enabled the creation of vast public spaces, including expansive palaces, public baths, and basilicas, which were themselves adorned with elaborate paintings, mosaics, and sculptures. This departure from the Greek preference for meticulously carved marble highlights the Roman emphasis on practicality, structural efficiency, and the ability to build on a grand, unprecedented scale.

Diverse Media and Expansive Purposes

Roman art embraced an astonishing variety of media and served broader societal purposes than many preceding cultures. While sculpture was highly esteemed, Roman artists excelled in wall painting, intricate mosaic work, sophisticated metalwork, detailed gem engraving, innovative glass production, and even numismatic art (coins). Unlike the Greeks, Romans frequently depicted everyday life, detailed landscapes, and specific historical events with remarkable realism. The towering commemorative columns of Trajan and Marcus Aurelius, for example, are covered with continuous spiral reliefs that vividly depict military campaigns and imperial achievements, serving as monumental historical documents in stone. Is this not a fascinating early form of historical documentary through art, distinct from Greek mythological allegories?

Portraiture: Capturing Reality and Identity

Realism extended significantly into Roman portraiture. Artists meticulously captured unique individual traits and distinct personalities, moving away from idealized, generic forms. Roman portrait busts, often found in family tombs or adorning private homes, offer invaluable insights into the lives, appearances, and values of individual citizens, from emperors to former slaves. This intense focus on individualized features and the portrayal of age, wrinkles, and even perceived flaws stands in stark contrast to the idealized Greek forms. This profound realism reflects Roman practicality, a strong emphasis on personal identity, and the value placed on ancestry within their society.

Art for All: Popularization and Accessibility

Crucially, Roman art became accessible to a much wider segment of society than in many previous cultures. Private patronage flourished, and the mass production of artworks (through techniques like mold-making for terracotta reliefs or standardized statuary types) made art more affordable and widely available. Roman wall paintings, dynamic mosaics, and various decorative objects became common features ador