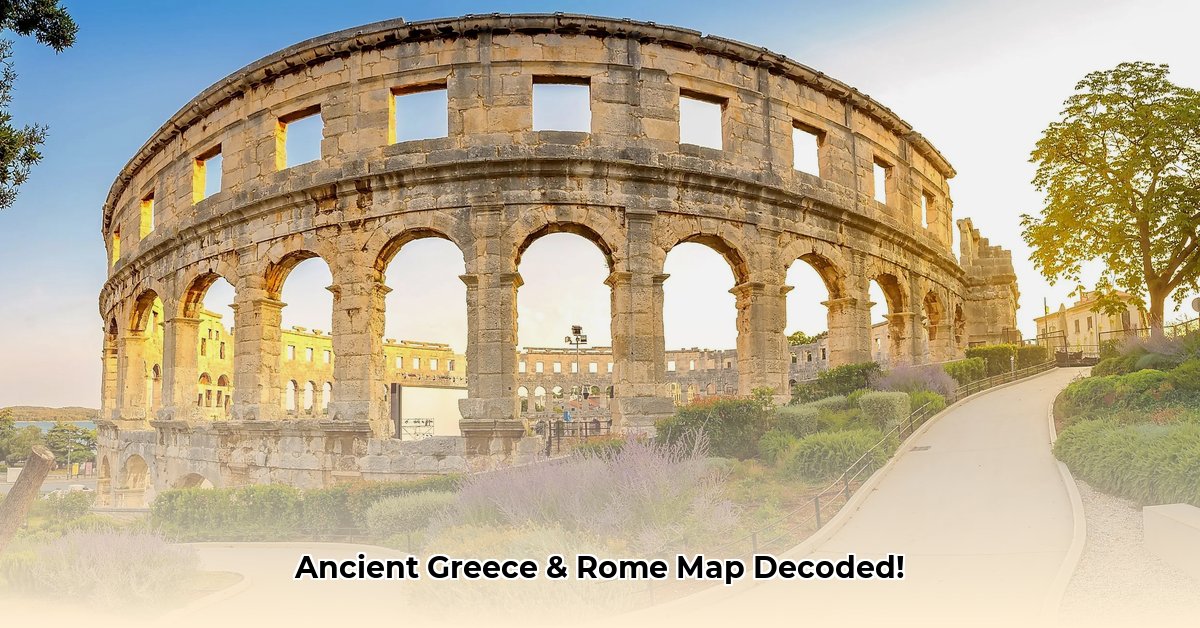

Ancient maps are far more than mere historical documents; they are profound artifacts, critical tools for understanding the core values, knowledge systems, and navigational approaches of past civilizations. From the philosophical inquiries of early Greek thinkers to the pragmatic imperial administration of Rome, the way a culture chose to represent its world offers unparalleled insight into its priorities and worldview. This article delves into the distinct cartographic philosophies of the Greeks and Romans, highlighting how their unique geographies and societal structures shaped their maps, and exploring the enduring lessons these ancient representations hold for our modern understanding of space and power. Here’s more on a map of ancient lands. This article delves into the distinct cartographic philosophies of the Greeks and Romans, highlighting how their unique geographies and societal structures shaped their maps, and exploring the enduring lessons these ancient representations hold for our modern understanding of space and power.

Greek Mapmaking: A Philosophical Quest for Cosmic Understanding

For early Greek thinkers, mapmaking transcended simple geographical plotting; it was an exercise deeply rooted in philosophical inquiry and a grand attempt to comprehend the cosmos. Anaximander of Miletus, credited with creating one of the earliest known maps of the Earth in the 6th century BCE, did not aim for precise geographical accuracy as we understand it today. Instead, his work, like that of Hecataeus of Miletus who refined Anaximander’s world map, represented a conceptualization of the known world—a disc surrounded by ocean—reflecting an emerging scientific and philosophical understanding of humanity’s place within the universe. These maps were attempts to explain the “why” and “how” of the world, integrating early observational science with profound philosophical contemplation.

The fragmented geography of ancient Greece, characterized by countless islands and independent city-states, profoundly influenced this decentralized approach to thought. This environment fostered intellectual hubs like the Athenian Agora, where philosophical debates and scientific investigations flourished, shaping their cartographic understanding. Figures such as Pythagoras envisioned a cosmos governed by mathematical harmony, influencing later astronomical models, while Eratosthenes of Cyrene, in the 3rd century BCE, astonishingly calculated Earth’s circumference with remarkable precision and pioneered a system of latitude and longitude. Greek contributions extended to mathematical geography, developing sophisticated geometric models and early map projections. These advancements were not solely academic; they supported practical applications such as calendar creation and early navigation, reflecting a holistic pursuit of knowledge that sought to unify the terrestrial with the celestial. Later, Claudius Ptolemy in the 2nd century CE, though living under Roman rule, codified much of ancient Greek geographical knowledge in his Geographia, establishing principles of latitude, longitude, and map projection that influenced cartography for over a millennium.

Roman Mapmaking: Engineering an Empire on Paper

In stark contrast to the Greeks, the Roman approach to mapmaking was profoundly pragmatic, grounded in the tangible needs of a sprawling empire. Roman maps served as indispensable tools for connecting vast territories, deploying legions with unparalleled efficiency, and administering an intricate imperial system. Practicality was paramount, reflecting Rome’s emphasis on engineering, logistics, and governance.

The Tabula Peutingeriana, a medieval copy of an authentic Roman road map, stands as a quintessential example of this utilitarian cartography. This was not a geometrically accurate world map but an incredibly detailed, albeit visually distorted, guide to the empire’s pulsating road network. It meticulously highlighted critical trade routes, military outposts, and significant urban centers. Scale and strict geographical accuracy were secondary; instead, the map optimized for functional clarity and the practical demands of the Roman state. For instance, the Tabula Peutingeriana provides detailed data on routes, distances, settlements, and resources, containing over 555 cities and 3,500 place names across 11 surviving segments. This level of detail perfectly illustrates their focus on logistical capabilities and imperial reach. While the Greeks pondered the reason for a road’s existence, the Romans were fixated on the how—how many soldiers could march down it in a day, how quickly goods could be transported, and how effectively the empire could be managed and controlled.

Roman administration of Greece, known as the province of Achaea, after its annexation in 146 BCE, saw regions like Corinth, destroyed and then resurrected by Julius Caesar as a Roman colony, become key administrative centers. Under the firm rule of emperors like Augustus, peace and efficient governance were prioritized. Roman cartography supported this centralized control, ensuring that resources could be allocated, taxes collected, and legions moved swiftly across newly pacified or integrated regions. Beyond grand road maps, Roman cartographers produced practical cadastral maps for land ownership, military itineraries, and even highly detailed urban plans like the Forma Urbis Romae, a massive marble map of ancient Rome, underscoring their dedication to precise administrative and engineering needs.

A Tale of Two Cartographies: Greek vs. Roman Approaches

To truly grasp the distinct genius of each civilization, a direct comparison of their cartographic endeavors proves invaluable. The Greeks, nurtured by independent city-states, a vibrant intellectual tradition, and an insatiable philosophical curiosity, conceived maps that mirrored a decentralized, theoretical understanding of the world. Their focus was on the cosmos, mathematical principles, and the abstract representation of phenomena. In stark contrast, the Romans, as architects of a highly centralized empire built on military might and administrative efficiency, produced maps explicitly designed for practical control, efficient communication, and strategic military deployment.

Scholars continue to debate the extent of Greek influence on Roman cartography. Some argue that Roman cartographers, while drawing on Greek mathematical and astronomical knowledge, ultimately developed a unique, utilitarian style tailored to their imperial needs. Others contend that the Romans significantly improved upon Greek methods by refining techniques for surveying and measuring distances, albeit often sacrificing geographical precision for functional clarity. This ongoing discussion highlights a key area of study in historical cartography: was Roman mapmaking an evolution of Greek methods or a fundamental divergence driven by distinct societal priorities? The key differences are strikingly clear in their output:

| Feature | Greek Maps | Roman Maps |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Purpose | Philosophical understanding, exploring the cosmos and human place | Practical administration, imperial control, military logistics |

| Accuracy Focus | Conceptual, relative positioning, mathematical principles | Functionally accurate for routes, distances, and administrative areas |

| Key Examples | Works of Anaximander, Hecataeus, Eratosthenes, Ptolemy | Tabula Peutingeriana, Cadastral Maps, Forma Urbis Romae |

| Influence of Geography | Reflected fragmented city-state structure and sea-centric views | Facilitated centralized power stemming from Rome and vast land empire |

| Cartographic Goal | Understanding the world through philosophical and scientific lens | Connecting and controlling the world through infrastructure and administration |

| Common Materials | Papyrus (a practical, portable material) | Animal skin (durable for travel), marble (for enduring public display) |

Beyond the Parchment: Enduring Lessons from Ancient Cartography

These ancient maps are more than mere historical curiosities; they offer profound, actionable insights for contemporary society. Comparing these ancient approaches to representing the world reveals how deeply geography, cultural values, and political structures shape the very tools we use to understand and manage our environment. Modern digital tools and initiatives, such as the Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire (DARE) and projects supported by the Pelagios community, demonstrate how current geospatial technologies build upon and help decode these ancient efforts, allowing for new discoveries and interpretations.

Here’s how this knowledge can be leveraged today:

- For Educators: Integrate ancient maps into history, geography, and cartography curricula to vividly illustrate contrasting worldviews and the evolution of spatial thinking. Assign comparative projects analyzing the symbolic, pragmatic, and philosophical representations on maps like the Tabula Peutingeriana versus the conceptual scope of Greek maps. This comparative study significantly enhances students’ understanding of classical civilizations, geographical reasoning, and the interplay between culture and cartography.

- For Policymakers: Study how ancient empires utilized geographical knowledge for governance and control. The Roman emphasis on infrastructure and meticulous mapping for administrative efficiency offers invaluable lessons in modern strategic planning, urban development, and resource deployment, particularly for large, diverse nations. Their approach to integrating newly acquired territories through mapping can inform contemporary regional planning and resource management.

- For Cultural Institutions and Tourism: Curate interactive exhibits showcasing these ancient maps. Imagine digital installations allowing virtual journeys along the Tabula Peutingeriana, highlighting trade routes and military outposts, or exploring Anaximander’s cosmic vision through immersive displays. Such initiatives can transform cultural tourism, offering rich, immersive experiences that deepen public engagement with history and stimulate local economic development. Physically tracing surviving sections of Roman road networks, often revealed through modern mapping, can engage communities and foster a tangible connection to the past.

- For Researchers: Utilize modern Geographical Information Systems (GIS) tools and digital humanities methodologies to cross-reference historical map data with archaeological finds, ancient texts, and environmental data. This interdisciplinary approach can lead to groundbreaking discoveries, refine our understanding of ancient settlement patterns, economic networks, and environmental changes, and reveal previously unknown connections within ancient spatial organization. Digital preservation and analysis of these antique documents become key to unlocking new insights.

The ways Greeks and Romans chose to depict their worlds profoundly reveal their core values and societal priorities. This study challenges us to critically consider how our own modern maps, from digital navigation aids to global satellite imagery, both reflect and shape our contemporary perceptions, power structures, and understanding of the world. Ultimately, these ancient cartographic endeavors were not just about lines on a surface; they were about how these foundational civilizations saw their place in the world, how they understood and controlled their environment, and how they used that knowledge to shape their destinies. This enduring lesson remains remarkably relevant today.