Beyond the grandeur of their architectural marvels and the discipline of their legendary legions, the ancient Romans were a people deeply immersed in play. From the simplest toys clutched by infants to the elaborate, often brutal, spectacles that captivated hundreds of thousands, games served as far more than mere diversions. They were intricate reflections of Roman society, powerful instruments of political control, nuanced expressions of religious belief, and even catalysts for profound social and moral debates. Learn more about Roman games and leisure activities. Prepare to delve into the fascinating, multifaceted world of ancient Roman leisure, where every pastime, from a child’s humble doll to the thunderous chariot race, offers a unique lens into one of history’s most enduring empires.

Playthings of Childhood: Shaping Roman Futures

Imagine peering into a Roman child’s world; their toys, crafted from diverse materials, were not simply objects of amusement but foundational tools for education and social conditioning. For the youngest Romans, babies played with charming crepitacula – rattles often shaped into boxes, spheres, fruits like pomegranates, or animals such as owls and hedgehogs. Made from wood, bronze, or clay, and sometimes containing pebbles to make noise, these served to entertain and soothe. Similarly, crepundia, small toys shaped like axes, swords, animals, or crescent moons, were crafted from clay or bronze, sometimes intricately from gold or silver for wealthier families. Inscribed with a parent’s name, these rattles could even aid in returning a lost child—a poignant dual purpose.

As children grew, their toys mirrored the roles they were expected to embody. Toddlers used pull toys, pushcarts, and wooden carts to aid their first steps. Boys, destined for military or public life, engaged with spinning tops, metal hoops (sometimes fitted with rings to make noise, as mentioned by Propertius and Martial), wooden swords, and kites. Toy chariots, pushed with sticks or pulled by strings, offered miniature battle or race simulations; some even featured tiny mouse-drivers, or were large enough for boys to ride, pulled by goats, peacocks, or dogs, as depicted on sarcophagi. These playthings instilled values of courage, discipline, and competitive spirit, subtly preparing them for future civic and martial duties.

Girls, conversely, fostered domestic and societal ideals through their dolls. Crafted from bone, terracotta, cloth, alabaster, wood, wax, marble, or ivory, Roman dolls often featured jointed limbs. Examples from the Catacombs of Priscilla and Callixtus even show dolls with detachable limbs. Many dolls portrayed physical similarities to empresses like Faustina the Elder and Faustina the Younger, who epitomized Roman ideals of fecunditas (fertility) and motherhood. These dolls, adorned with miniature fashion and jewelry, were designed to encourage young girls to embrace the Roman ideal of a housewife. A poignant tradition, noted by Horace and Persius, saw girls dedicating their dolls to the Lares (household guardians) or Venus upon reaching adulthood or marriage, signifying their transition from childhood play to mature responsibilities. While less common, male dolls, including soldier and gladiator figures with mobile limbs, were also part of Roman children’s play, occasionally found in the graves of girls, such as the soldier doll discovered in the tomb of 10-year-old Claudia Victoria in Lyon.

Beyond structured toys, Roman children often improvised. They played games involving nuts, a pastime so prevalent that the phrase Nuces relinquere (“to leave the walnuts behind”) metaphorically signified abandoning childhood for maturity. Children would build pyramidal structures with nuts (Nuces Castellatae) and attempt to knock them down, or roll nuts off boards to hit others on the floor, as described in the Pseudo-Ovidian poem Nux. Another variation, orca, involved tossing nuts into a narrow jar. Materials like pebbles, shells, coins, or knucklebones also served as impromptu playthings. These games, regardless of their simplicity, reinforced practical skills and fostered social interaction among the youth.

The Emperor’s Arena: Public Spectacles and Political Grandeur

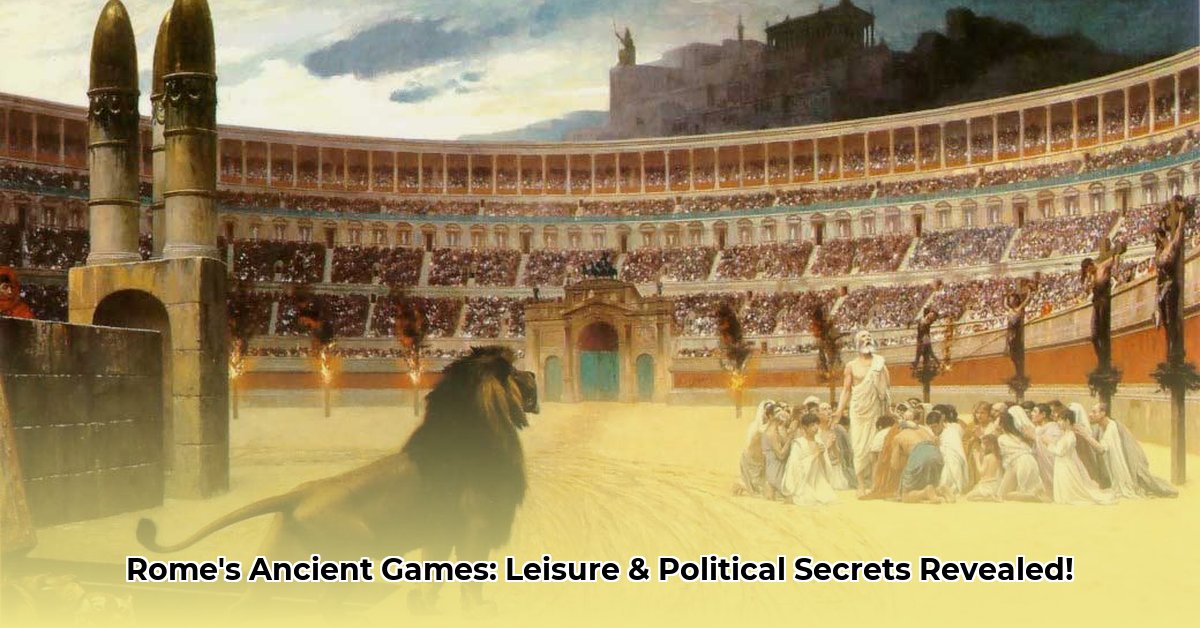

For the vast majority of Romans, entertainment reached its zenith in the colossal public spectacles —the renowned “bread and circuses” (panem et circenses)—a phrase that perfectly encapsulates their dual purpose. These events, far from mere entertainment, were a shrewd political tool wielded by emperors and politicians to appease the populace, demonstrate wealth, reinforce social hierarchies, and, crucially, maintain control over the masses by distracting them from political discontent.

Chariot racing was undeniably the most popular and thrilling spectacle of Roman life. Held in immense venues like the Circus Maximus, which could seat up to 250,000 spectators, these races fostered intense team loyalties akin to modern sports fandom. Four main factions—the Reds, Blues, Greens, and Whites—inspired rabid support, with fans wearing their team colors and engaging in fierce rivalries. Charioteers, often slaves, could achieve immense fame and fortune; Gaius Appuleius Diocles, a celebrated auriga, earned a sum equivalent to billions in modern currency over his 24-year career. The races were incredibly dangerous, with lightweight chariots and horses’ reins wrapped around drivers’ wrists, making crashes frequent and often fatal—a risk that only heightened the spectacle. Emperor Julius Caesar himself introduced chariot races to Rome, and subsequent rulers like Augustus further elevated their prominence.

Gladiatorial contests, initially originating from Etruscan funerary rites, evolved into a central pillar of public entertainment. Gladiators, typically slaves, prisoners of war, or condemned criminals (though some volunteered for glory), trained in specialized schools known as ludi. These combatants fought in diverse styles—from the heavily armed secutor to the net-wielding retiarius—creating dramatic and suspenseful confrontations. While often brutal, with death a common outcome (especially in sine missione fights, or those “without mercy”), many matches showcased remarkable skill and tactics, observed by referees. Emperors, including Commodus, were known to participate in these games themselves, blurring the lines between ruler and warrior. It is estimated that over 500,000 people and more than a million animals perished in the Colosseum alone during its operational history.

Beyond the iconic chariot races and gladiatorial duels, Roman spectacles encompassed a wider array of lavish displays. Naumachia, or mock naval battles, staged in artificial basins or flooded amphitheaters, were particularly grand. Julius Caesar organized the first such event in 46 BCE, flooding a basin near the Tiber for a battle involving 4,000 rowers and 2,000 combatants, all prisoners of war fighting to the death. Augustus also staged a famous Naumachia in 2 BCE, depicting a battle between Greeks and Persians. Venationes, or wild animal hunts, brought exotic and ferocious beasts from across the empire—lions, tigers, bears, elephants, hippos, even crocodiles—into the arena to fight each other or armed hunters (venatores). Marcus Fulvius Nobilior introduced venationes to Rome around 189 BCE. These hunts often showcased Rome’s dominance over nature and its vast imperial reach; for instance, 9,000 animals were reportedly killed during the inauguration of the Colosseum. Criminals, known as bestiarii, were sometimes executed by being thrown to these wild animals. Another unique equestrian event was the Lusus Troiae (“Troy Game”), a mock display of war performed by young boys of the noble Eques class, involving complex horsemanship and military drills. The theatrical Ludi Scaenici, encompassing dramas, comedies, mime, and pantomime, provided cultural enrichment, while public executions were often staged theatrically, sometimes incorporating mythological themes to reinforce Roman justice.

These grand spectacles, held in engineering marvels like the Colosseum and Circus Maximus, not only captivated the public’s senses but also reinforced the strict social stratification of Roman society, with seating arrangements meticulously dictating status, from the elite in the front rows to slaves and soldiers in designated sections.

Dice with Destiny: Roman Gambling’s Risky Business

Much like modern societies, ancient Rome harbored a profound and widespread fondness for games of chance, particularly dice. From emperors to common citizens, rolling the dice was a ubiquitous pastime, often involving wagers of denarii and other valuables. Emperor Claudius, a notorious enthusiast, reportedly had a special gaming table installed in his carriage for continuous play and even penned a now-lost book, De arte aleae (On the Art of Dice). Augustus was known to offer sums to guests to encourage betting, and other emperors like Caligula, Nero, and Commodus were depicted as avid gamblers, though such descriptions might have been part of smear campaigns against unpopular rulers.

Despite its pervasive popularity, gambling carried a significant social stigma and was often technically outlawed. Roman moralists and satirists, including Ammianus Marcellinus, Horace, and Juvenal, vociferously condemned it. Marcellinus attributed the decline of Rome itself to the pervasiveness of gambling, claiming it prevented “