Ever wondered what it was really like to dress like a Roman soldier? Forget those Hollywood portrayals with every legionary in identical, gleaming metal suits. The truth is, uniformity in the Roman army was a concept that evolved, adapting to diverse climates, tactical needs, and economic realities. Being a Roman legionary was far more about practical clothing and gear designed for survival and effectiveness across vast, varied terrains. This is your comprehensive look into what Roman soldiers actually wore, from their foundational garments and robust footwear to their protective armor and specialized weaponry, exploring how their attire shifted over centuries and according to their roles. You can explore more about the specificities of Roman Military Clothing online.

Ancient Roman Military Attire: A Blend of Pragmatism and Adaptation

The unprecedented success of the Roman military derived significantly from its pragmatic approach to soldier outfitting and its remarkable ability to adapt. For centuries, the ancient Roman soldier uniform was not merely a symbol of martial prowess but a testament to logistical ingenuity and a constant willingness to incorporate new, effective designs. Far from a static image of a legionary in lorica segmentata (segmented plate armor), Roman military attire was dynamic, equipping each soldier for deployments ranging from the scorching deserts of Syria to the damp, cold frontiers of Britannia.

At the core of every Roman soldier’s ensemble was the tunica (tunic), a simple, shirt-like garment typically made from wool or linen. The material choice was often dictated by climate: lighter linen for hot regions to prevent heatstroke, and heavier wool for much-needed warmth in chilly areas. Its color was usually undyed (off-white) or dyed red with madder. While all soldiers wore tunics, their length could signify rank or status, with senior commanders occasionally favoring longer versions.

Essential for long marches and rugged terrain were the caligae (hobnailed sandals). These sturdy, open-toed military boots, worn by legionaries and auxiliaries throughout the Roman Republic and Empire, were engineered with heavy, studded soles to withstand thousands of miles of marching, effectively preventing blisters and conditions like trench foot by allowing air circulation. Yet, for colder environments, the pragmatic Romans adopted braccae (trousers), often made of wool, from encountered peoples. This demonstrated their flexibility and dedication to practical solutions over strict adherence to tradition. To guard against chafing from armor, soldiers wore a focale (a wool or linen scarf) around their neck. The cingulum militare (military belt) was a standard accoutrement, not only securing clothing but also serving as a suspension point for a dagger and a decorative “apron” of studded leather strips called pteruges (or pteryges), which could also adorn shoulders. These pteruges, originally offering minor protection, evolved into a display of rank and campaign history, adorned with metal discs and tokens.

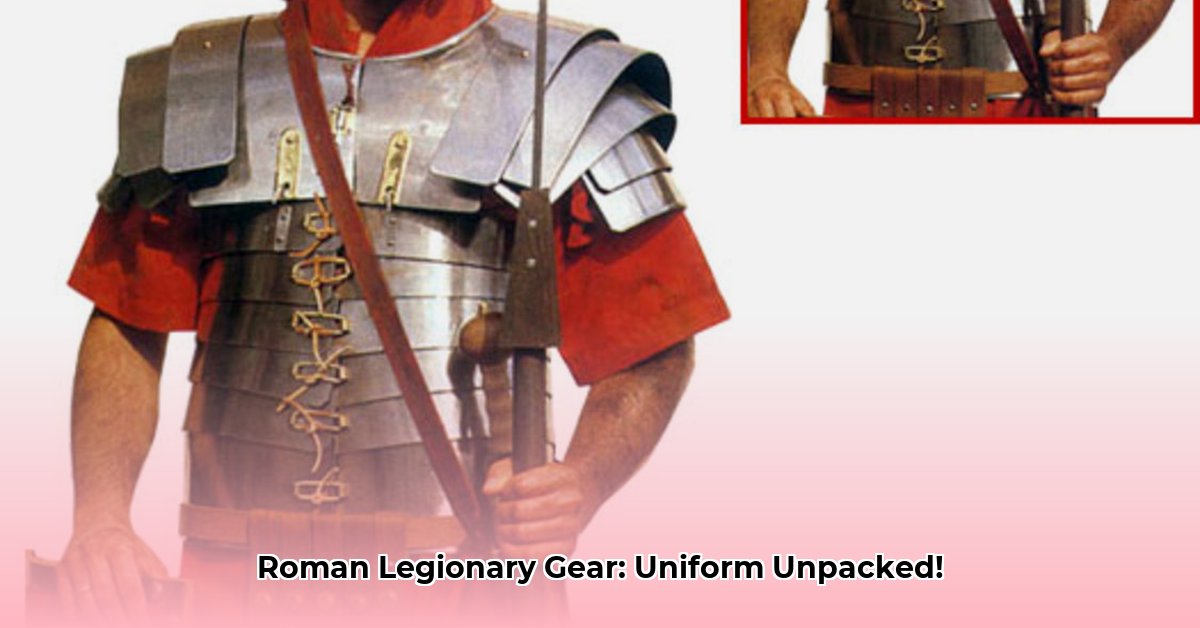

The Evolution and Purpose of Roman Armor

Roman armor is the most iconic visual element of their soldiers, yet its application was far from monolithic. While the lorica segmentata is widely recognized, it represents only one phase and type of armor. Its fame often overshadows the more common and long-lived lorica hamata (chainmail) and the versatile lorica squamata (scale armor).

Lorica Hamata (Chainmail): Introduced by the Celts and adopted by the Romans in the 3rd century BC, this was arguably the most common and versatile form of Roman armor for nearly seven centuries. Constructed from thousands of interlocking iron or bronze rings (each typically 5-9mm in diameter, 1-2mm thick), it offered excellent flexibility and superior protection against slashing attacks and moderate piercing blows. A full lorica hamata could weigh up to 22 lbs (10 kg) and was worn by legionaries, auxiliary troops, and even some officers, remaining the primary protective gear for much of the Imperial period. Its open, U-shaped neckline and shoulder doubling provided additional protection.

Lorica Segmentata (Segmented Armor): This distinctive armor, characterized by overlapping horizontal metal strips fastened by leather straps and internal buckles, peaked in use primarily between the 1st and 3rd centuries AD, often replacing lorica hamata for legionaries. Examples like the Kalkriese, Corbridge, and later Newstead types show its continuous refinement. It offered superior protection against direct impacts and thrusts due to its solid plates. However, its complex construction meant higher production costs and more demanding maintenance with numerous small parts. It necessitated the wearing of a subarmalis—a padded linen or wool undergarment—to absorb sweat, prevent chafing, and distribute blunt force impact. Its eventual decline was due to logistical challenges in mass production and repair, leading to a return to the more easily repairable and cost-effective lorica hamata.

Lorica Squamata (Scale Armor): Made of small, overlapping metal scales (bronze or iron) sewn onto a fabric backing, this armor provided a good balance of protection and flexibility. It was particularly favored by centurions, cavalry, standard-bearers, and auxiliary troops. While offering better defense against blunt force than chainmail, it was potentially vulnerable to upward thrusts in the gaps between scales. Despite this, its extensive use beyond the Roman Empire, in Persia and Byzantium, attests to its effectiveness.

Pectorale: In the early Republic, less wealthy soldiers, such as the Hastati, might use a simple bronze or leather pectorale—a rectangular chest plate—held by leather straps, a more economical alternative to full body armor.

Shields and Helmets: The Frontline Defense

Beyond body armor, Roman soldiers relied heavily on their shields and helmets for critical protection and tactical advantage.

Scutum (Shield): The iconic large, rectangular, and cylindrically curved shield (scutum) was the primary defense of Roman legionaries. Typically weighing 13-22 lbs (6-10 kg) and measuring approximately 3.9 ft (120 cm) high and 2.9-3.2 ft (90-100 cm) wide, it was constructed from multiple layers of glued birch plywood, reinforced with leather and linen, and edged with bronze fittings. Its curvature allowed a soldier to effectively deflect blows and form the famous testudo (tortoise) formation, where overlapping shields created an impenetrable shell against projectiles during sieges or intense missile fire.

Galea (Helmet): The galea, or helmet, was indispensable for protecting the Roman soldier’s head. Roman helmets, primarily made of bronze or iron, evolved through various styles, including the Coolus, Montefortino, and later Imperial types (such as the Gallic and Italic series), each offering different levels of protection and design features like reinforced brows and broad neck guards. Many helmets incorporated cheek guards and sometimes face masks, particularly for gladiators. For parades or to appear more intimidating in battle, Roman soldiers, especially centurions, would attach a crista (crest) of horsehair or feathers, which could also serve as identification for different units.

Greaves: Primarily worn by officers (such as an optio or centurion) as symbols of status and for added protection, greaves (ocreae) covered the lower legs, particularly the vulnerable tibia bone. Made of bronze or iron, they were often padded internally for comfort and shock absorption. Interestingly, during Julius Caesar’s campaigns, some soldiers were only required to wear one greave, relying on their scutum to protect the other leg.

Weaponry: Precision and Pragmatism on the Battlefield

The weapons carried by Roman soldiers were as critical as their armor, reflecting a blend of effective design and tactical insight.

Gladius (Sword): The gladius, a relatively short, double-edged sword typically 18-24 inches (45-61 cm) long, was the standard sidearm for Roman legionaries and most gladiators. Its tapered, leaf-shaped blade was supremely effective for thrusting and close-quarters combat. Roman officers typically wore their swords on the right side, while regular soldiers carried theirs on the left in a wooden, leather-covered scabbard.

Pugio (Dagger): While its universal use by non-officers remains debated by some historians (like Polybios), the pugio, a short dagger with a broad, leaf-shaped blade (7-11 inches or 18-28 cm), was a common personal weapon, often used for utility as well as close-range fighting.

Pilum (Javelin): The pilum was perhaps the most ingenious and tactically significant Roman weapon, often overlooked in popular culture. This specialized javelin, roughly 6.5 ft (2 meters) long, consisted of a wooden shaft and a long, slender iron shank culminating in a hardened pyramidal tip. Designed to be thrown in volleys at distances of 16-32 yards (15-30 meters), its brilliance lay in its deliberate design flaw:

- Bending Mechanism: The iron shank was usually made of softer metal just below the hardened tip, or attached with a combination of iron and wooden rivets. Upon impact with an enemy shield or armor, the pilum’s tip would penetrate, and the iron shank would bend or the wooden rivet would break, making the weapon useless for the enemy to throw back.

- Shield Immobilization: If a pilum pierced an enemy’s shield, its pyramidal tip and bent shank would prevent it from being easily pulled out or chopped off. This forced the enemy soldier to discard their shield, leaving them vulnerable to the ensuing Roman charge with the gladius. Julius Caesar famously recounted battles where pila pinned Gallic shields together, rendering entire enemy formations helpless.

Hasta (Thrusting Lance): While the pilum was widespread, the Hasta—a long thrusting lance—was the primary weapon for the Triarii (the third line of battle in the manipular legion) and was also used by early Roman hoplite-style soldiers. Its use by the Triarii signified their role as a steadfast, last-resort defensive line, designed to hold ground rather than engage in javelin volleys.

Spatha (Long Sword): As the Empire progressed, the spatha, a longer sword (24-39 inches or 60-100 cm), gained popularity, especially among Roman cavalry in the 1st century AD, and later became more common for legionaries from the 2nd to 3rd centuries AD, coinciding with a shift towards spear-based tactics over heavy javelins.

The Roman Soldier Throughout the Ages: Pre- and Post-Marian Reforms

The notion of a “standard” Roman soldier uniform is best understood through the lens of historical periods, particularly the pivotal Marian Reforms of 107 BC. Before these reforms, Roman soldiers were citizen-militia who bore the cost of their own equipment, leading to significant variations based on personal wealth. The army operated under a manipular system, with distinct infantry groups:

- Velites: The youngest and least-armed citizens (17-25 years old), functioning as light skirmishers. They wore a small shield (parma) and a hardened leather cap, armed with seven light javelins and a gladius. Their role was to harass the enemy before the main lines engaged, and they were particularly effective against war elephants due to their mobility.

- Hastati: The first line of heavy infantry (25-30 years old), equipped with a scutum, a bronze helmet (cassis), a pectorale (chest plate), two pila, and a gladius. Their goal was to engage and exhaust the enemy.

- Principes: The second line of battle (30-40 years old), considered the most experienced and best-equipped. They carried a scutum, a bronze helmet, lorica hamata (chainmail), two pila, and a gladius. Their role was to break the enemy lines after the Hastati had softened them.

- Triarii: The oldest and most veteran soldiers (40-45 years old), forming the third and final line. They were equipped with a scutum, a bronze helmet, lorica hamata, a hasta (thrusting lance) instead of javelins, and a gladius. They served as the ultimate reserve, and potentially as a barrier to prevent younger soldiers from fleeing.

The Marian Reforms, attributed to General Gaius Marius, fundamentally transformed the Roman army into a professional, state-equipped force. This eliminated age and wealth requirements, making soldiering a career and leading to greater standardization of equipment. After 107 BC, the typical Roman legionary (miles) was uniformly equipped with a scutum, a galea (helmet), lorica hamata (which remained prevalent) or later lorica segmentata, two light pila, and a gladius. This professionalization, while bolstering military effectiveness, also inadvertently