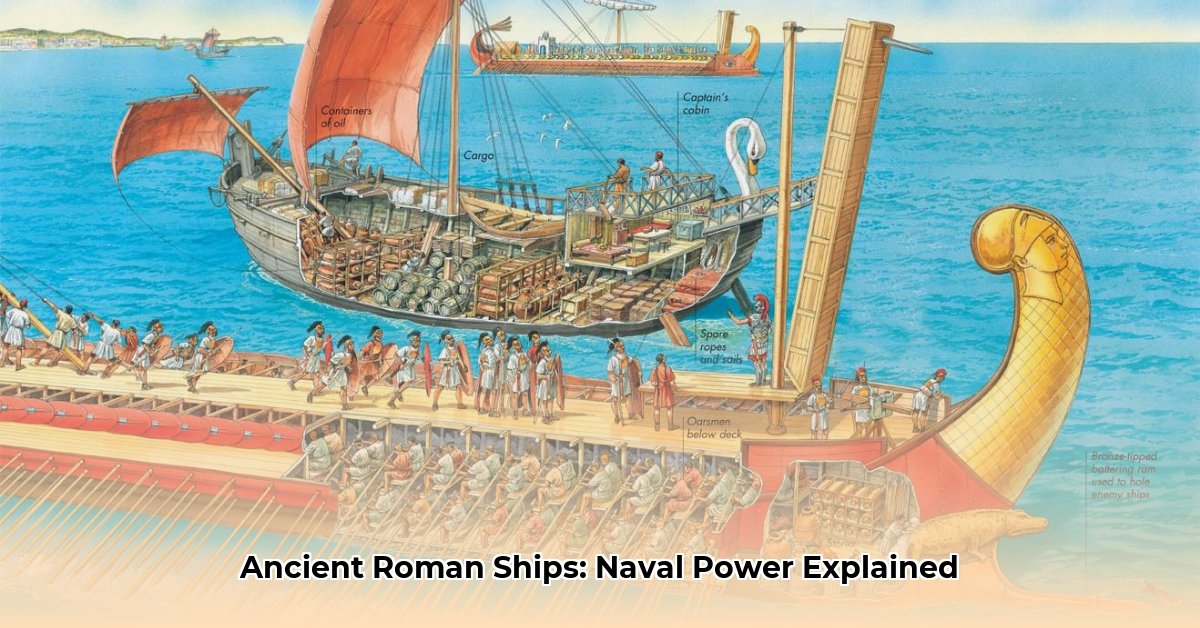

Ancient Rome, renowned for its terrestrial empire, also forged a formidable naval power that was instrumental in its expansion and enduring success. Far from being natural seafarers, the Romans engineered maritime dominance through adaptation, innovation, and formidable strategic application. This comprehensive exploration delves into how they transformed from a land-based people to rulers of the Mediterranean, establishing “Mare Nostrum”—Our Sea—and securing their empire through unparalleled naval might. Their journey, marked by ingenious shipbuilding, refined navigational methods, and decisive naval tactics, offers profound insights into the pivotal role of maritime power in shaping ancient civilizations and continues to inform modern studies.

The Roman shield was key army equipment.

Core Insights into Roman Naval Supremacy

- Strategic Adaptation: Roman naval power was fundamentally built on capturing and meticulously reverse-engineering the advanced shipbuilding techniques of their rivals, particularly the Carthaginians.

- Diverse Fleet Development: They cultivated a specialized fleet, comprising agile warships for military projection and high-capacity merchant vessels essential for economic stability and provisioning the vast empire.

- Revolutionary Shipbuilding: A pivotal shift from the “hull-first” to the more efficient “frame-first” construction method around the 1st century CE dramatically enhanced the speed and scale of ship production.

- Navigational Prowess: Despite lacking modern instruments, Roman mariners mastered sophisticated navigational techniques, utilizing celestial bodies, coastal landmarks, and written sailing directions to traverse vast distances.

From Landlubbers to Lords of the Waves

Initially, Rome possessed a minimal naval force, relying on allies for maritime presence. This changed dramatically with the First Punic War (264–241 BCE), when they confronted Carthage, the undisputed naval superpower of the Western Mediterranean. Recognizing the existential threat, Rome embarked on an unprecedented shipbuilding program. Their tactical genius and resourcefulness shone through when they reportedly captured a Carthaginian quinquereme that had run aground off Sicily. This captured vessel served as a blueprint, allowing Roman shipwrights to reverse-engineer its design and rapidly construct their own fleet, often in remarkable numbers, such as 100 quinqueremes in a single winter. While initial Roman copies were heavier and less maneuverable than their Carthaginian counterparts, their sheer production capacity and innovative tactics quickly leveled the maritime playing field.

The Carthaginian Catalyst: The Corvus and Naval Transformation

The Roman adoption of the corvus, a hinged boarding bridge with a heavy spike, directly addressed their initial inexperience in traditional naval maneuvers like ramming. This innovation transformed sea battles into land engagements, allowing Roman legionaries, superior in close-quarters combat, to board and overwhelm enemy ships. The corvus significantly contributed to decisive Roman victories at Mylae (260 BCE) and Cape Ecnomus (256 BCE)—one of the largest naval battles in history. Although the corvus added weight to the prow, potentially compromising maneuverability and seaworthiness in rough conditions (leading to its eventual abandonment after significant losses in storms, such as the 255 BCE disaster off Sicily), its strategic impact during the critical early Punic Wars was undeniable.

Fleet Diversity: Warships and the Lifeline of Commerce

The ingenuity of Roman naval strategy extended far beyond offensive warships. Their success hinged on a versatile fleet capable of dual military and commercial roles—a necessity for an empire that spanned continents.

Purpose-Built Vessels for Empire Building

Roman warships were designed for speed, maneuverability, and combat. The trireme, a galley with three tiers of oarsmen, was a dominant early type, though it was eventually superseded by larger vessels. The quinquereme, meaning “five-oared” (likely implying five oarsmen per vertical file of oars, not five banks), became the workhorse of the Roman fleet during the Punic Wars, typically measuring around 45 meters (150 ft) long, 5 meters (16 ft) wide, displacing about 100 tonnes, and carrying crews of 300 rowers and up to 120 marines. These powerful galleys were equipped with formidable bronze rams and provided platforms for catapults, ballistae, and large complements of infantry.

Beyond these heavy hitters, the Romans also extensively used lighter, faster vessels. The liburna, a compact bireme (two banks of oars) originating from Illyrian pirate designs, became a staple for patrols, raiding, and screening actions due to its agility. It played a crucial role in decisive battles like Actium (31 BCE), where Augustus’s lighter, more maneuverable liburnians outflanked Mark Antony’s larger, slower ships. The navis lusoria, a shallow-draft troop transport powered by soldier-oarsmen, patrolled the empire’s northern rivers like the Rhine and Danube, demonstrating Roman adaptation to diverse operational environments.

Simultaneously, merchant ships formed the economic backbone of the empire. The naves onerariae (burden ships), including types like the corbitae (grain ships) and actuariae (merchant galleys for speed-sensitive cargo), were optimized for maximum cargo capacity. These vessels, often reaching 40 meters (130 ft) in length and displacing hundreds of tons, transported vital goods: an estimated 150,000 tons of Egyptian grain annually to Rome, alongside wine, olive oil, raw materials (iron, copper, marble), and even live animals for gladiatorial games. It was more cost-effective to transport grain the length of the Mediterranean by sea than 24 kilometers (15 miles) by land. Without this diverse and effective fleet, Rome’s immense population could not have been sustained, nor could its vast territories have been effectively governed and connected.

The Evolution of Roman Shipbuilding Techniques

The advancements in Roman shipbuilding methodology profoundly impacted their naval capabilities, leading to more consistent, faster, and larger-scale construction.

From Hull-First to Frame-First: A Step-by-Step Revolution

Early Roman and Mediterranean shipbuilding primarily utilized the “hull-first” method, where planks were joined edge-to-edge (initially sewn, then with locked mortise-and-tenon joints from the 6th century BCE) to form the outer shell. Only after this shell was complete were the internal frames added. This artisanal, experience-driven process was arduous and limited the potential size and standardization of vessels.

However, a revolutionary shift occurred, gaining prominence around the 1st century CE: the transition to the “frame-first” method. This innovative approach reversed the sequence: the ship’s skeleton, or frame, was constructed first, defining the vessel’s shape and dimensions. Subsequently, the outer planking was attached to this pre-built frame. This method allowed for greater standardization, efficiency, and ultimately, enabled the mass production of ships on an industrial scale. For instance, Livy reports that Scipio Africanus commissioned 400 ships for the invasion of Africa in 204 BCE, and Julius Caesar ordered 600 oared transport ships in one winter for his planned invasion of Britain. This structural evolution profoundly impacted Rome’s naval capabilities, enabling them to build larger, sturdier vessels with unprecedented speed and consistency, mirroring Rome’s broader tendencies toward organization and large-scale engineering.

Mastering the Mediterranean: Ancient Navigation Skills

Navigating the open seas without modern instruments like GPS or compasses presented significant challenges. Roman mariners overcame these through acute observation, accumulated knowledge, and ingenious practical methods, often inheriting skills from master seafaring civilizations like the Phoenicians.

Navigating by Stars, Landmarks, and Written Guides

Roman navigators depended on a combination of astute observation and environmental understanding. For coastal voyages, landmarks such as distinctive coastlines, mountains, and islands served as crucial reference points. For longer journeys across the open sea, celestial navigation was vital, relying on the position of the sun at noon and prominent stars—especially Ursa Minor (the Little Bear), which Phoenician seamen recognized orbited closer to the celestial North Pole than Ursa Major—at night.

Additionally, they utilized periploi (written sailing directions), which detailed coastal routes, harbors, currents, and potential dangers. These guides, initially in Greek from the 4th century BCE, expanded to cover Atlantic routes and paths to India by 50 CE. Coordinating the hundreds of oarsmen on galleys was also critical; a musician, typically playing a wind instrument, or a person using hand gestures, would synchronize their strokes to maximize efficiency. Despite lacking modern technology, Roman sailors possessed impressive skills and a deep understanding of the marine environment, guiding their vessels effectively across the vast Mediterranean.

Enduring the Elements: Challenges of Ancient Seafaring

Even with their considerable naval successes, Roman mariners faced inherent limitations and challenges. Unpredictable weather conditions, particularly fierce storms, frequently disrupted trade and navigation. During the four winter months, commercial navigation was often suspended due to harsh seas, a period known as mare clausum (closed sea). Shipwrecks were a common and devastating occurrence, resulting in immense loss of life and valuable cargo, as evidenced by archaeological finds like the Monte Testaccio in Rome, a mountain of discarded amphorae reaching 35 meters (115 ft) high, containing the remains of approximately 53 million vessels. These factors underscore the formidable difficulties of maritime travel in antiquity, even for a powerful empire like Rome.

Naval Supremacy and the “Mare Nostrum”

The establishment of Roman naval dominance brought a new era of maritime security, fundamentally transforming the Mediterranean into a Roman highway—Mare Nostrum. This control was indispensable for the Empire’s stability, facilitating trade, communication, and military projection across its vast territories.

Tactics of Engagement: Ramming and Boarding

Roman naval warfare was often direct and brutal. Galleys were equipped with bronze rams, weighing up to 270 kilograms (600 lb), positioned at the waterline. While ramming an enemy ship’s stern or side aimed to disable it, it rarely sank a vessel unless heavily laden. Roman tactics also heavily favored boarding actions, where legionaries would storm enemy decks for hand-to-hand combat, leveraging their superior infantry. Formations, like the “testudo” (shielding rowers from projectiles), offered protection during engagements. The shift towards heavier ships with larger complements of marines reduced the reliance on highly skilled oarsmen, allowing Rome to field massive fleets rapidly.

Securing the Seas: Suppressing Piracy and Fostering Trade

With Rome’s ascendant naval power, piracy, a persistent and dangerous threat throughout antiquity, was largely suppressed under the meticulous campaigns of figures like Pompey the Great. This newfound security spurred tremendous growth in trade and economic activity across the Mediterranean. Major ports like Ostia, at the mouth of the Tiber, became bustling hubs, processing an estimated 1,200 large merchant vessels annually—about five per navigable day—crucial for supplying Rome itself. This control transformed the sea into a Roman highway, ensuring the dependable flow of commerce, troops, and essential resources throughout the Empire.

The Enduring Echoes of Roman Maritime Ingenuity

The impact of Roman naval power extended far beyond military dominance. It facilitated extensive trade networks, secured vital supply lines, and projected Roman influence across vast territories. Their shipbuilding techniques, such as the transition to frame-first construction, and sophisticated navigational methods were truly groundbreaking for their time, influencing later maritime technologies and practices. The sheer scale and organization of Roman shipping remained unsurpassed until the 16th century CE. The legacy of ancient Roman ships continues to shape our understanding of maritime history and the pivotal role of naval power in shaping civilizations.

Actionable Intelligence: Lessons for Today’s Scholars and Strategists

The study of ancient Roman ships and maritime practices offers valuable insights for various fields, providing a rich foundation for continued research and education.

Pathways for Historical and Archaeological Discovery

| Stakeholders | Short-Term (0-1 Year) | Long-Term (3-5 Years) |

|---|---|---|

| Historians/Archaeologists | Continue focused research on the financial implications and economic impact of Roman naval control, with a specific focus on the complex logistical routes used to transport vital grain and other commodities. Conduct systematic excavations of known Roman shipwrecks, such as those found in the Black Sea (e.g., Sinop D) or off Italy (e.g., Alkedo), and harbor sites (e.g., Portus, Puteoli) to discover new insights into specific ship designs, construction techniques, and the precise pathways of ancient maritime trade routes. Analyze recovered artifacts, like the 24 bronze rams from the Battle of the Aegates Islands, to confirm historical accounts and understand technological variations. | Initiate comprehensive, multi-disciplinary examinations of major Roman ports and associated commercial infrastructure, utilizing cutting-edge underwater archaeological methods and remote sensing technologies to precisely ascertain the actual sizes and capacities of discovered vessels and their operational contexts. Conduct in-depth comparative studies of Roman maritime routes with those of contemporary civilizations to understand their interconnectedness and role in broader ancient globalization and cultural diffusion. Expand research into the role of Roman provincial fleets (e.g., Classis Britannica) in maintaining frontier security and internal order. |

| Maritime Historians | Evaluate the specific impact of Roman adaptations in shipbuilding, such as the corvus or the frame-first method, by comparing them with contemporary maritime technologies and strategies from other cultures (e.g., Greek triremes, Carthaginian quinqueremes). | Develop sophisticated computational models and digital reconstructions of Roman-era trade routes, incorporating granular data from newly discovered archaeological finds, epigraphic evidence, and revised historical texts. Analyze the long-term environmental impact of extensive Roman shipping, including resource consumption for shipbuilding and potential effects on marine ecosystems. |

| Educators | Integrate Roman maritime history into national and regional school curricula, emphasizing its profound importance in shaping the course of Western civilization, global trade, and military strategy. Highlight specific examples such as the transportation of obelisks or the daily life aboard merchant ships to make the history tangible. | Collaborate with museums and heritage institutions to create engaging and highly interactive exhibits about ancient Roman ships, naval battles, and broader maritime achievements, leveraging virtual reality and augmented reality technologies to inspire future generations of historians, archaeologists, and maritime explorers. Develop public outreach programs focused on the sustainability lessons gleaned from Roman shipbuilding materials and practices. |

Mitigating Risks: Insights from Ancient Maritime Challenges

Understanding the challenges faced by Roman mariners can also offer valuable lessons in risk management and logistical planning.

| Risk Category | Risk Description | Mitigation Strategies (Ancient Roman Context) |

|---|---|---|

| Weather | Unpredictable and severe weather patterns, particularly intense winter storms, frequently disrupted trade, delayed voyages, and caused numerous shipwrecks, especially during the mare clausum period (approximately four winter months). | Employ highly experienced navigators who understood prevailing winds and currents. Adhere strictly to coastal routes during riskier seasons, allowing for quicker refuge. Invest heavily in the development and maintenance of sheltered harbors and natural anchorages to provide safe havens during squalls and storms. Leverage astronomical observations (e.g., North Star) for improved directional accuracy when open-sea conditions allowed. |

| Piracy | The persistent threat of piracy jeopardized valuable shipping routes, leading to significant cargo losses, disruption of supply lines, and danger to merchant crews and passengers. | Establish active and robust naval patrols, deploying agile vessels like liburnians throughout key shipping lanes to deter and intercept pirate activity. Implement mandatory convoy systems for high-value cargo (e.g., grain from Egypt). Offer substantial rewards for the capture of pirates and the recovery of stolen goods. Invest in secure port facilities with fortified walls and watchtowers to protect docked ships and cargo. |

| Ship Damage | Shipwrecks, whether due to storms, combat, or structural failure, resulted in catastrophic loss of life, valuable cargo, and critical vessels, severely impacting imperial supply lines and military readiness. | Continuously improve shipbuilding standards and construction techniques, such as the adoption of frame-first methods for increased structural integrity. Enhance navigational aids, including detailed periploi and practical knowledge of sea conditions, to avoid hazardous areas. Establish rudimentary but effective search and rescue operations for distressed vessels, including coastal watchtowers and rapid deployment of smaller aid ships. Maintain reserves of ships and materials for rapid replacement. |

| Logistics | The complex logistical challenges of transporting essential goods and large military forces across vast distances under varying conditions. | Develop highly efficient and purpose-built port facilities (e.g., Ostia, Puteoli) with extensive warehousing and loading/unloading capabilities. Standardize measures and containers for cargo (e.g., amphorae) to optimize storage and handling. Facilitate robust communication networks between ports, military commands, and the capital to ensure timely delivery and coordination. Implement organized convoy systems for military deployments and large-scale grain shipments. |

| Economic | Fluctuations in market demand, supply disruptions, and economic policies that could negatively impact maritime trade volumes and profitability. | Diversify trade routes and sources of essential goods to mitigate risks from single-point failures or regional instability. Promote fair trade practices and establish legal frameworks to protect merchants. Implement strategic economic policies, such as the annona system for grain, to stabilize markets and ensure consistent supply of essential goods, preventing price spikes and social unrest. Maintain strategic reserves of critical commodities. |

[Citation: World History Encyclopedia, Wikipedia, Naval Encyclopedia, Vita-Romae]

- Level Up Your Legion: Ancient Rome Games, Ranked (2024) — From Caesar to Indie Gladiators! - August 18, 2025

- Uncover ancient roman shield tactics for legionary dominance: military history revealed - August 18, 2025

- Unveiling the Ancient Roman Bed: Trends Influencing Modern Design Today [Historical Reference] - August 18, 2025