Ever wondered how the Roman Empire forged an dominion across vast continents, achieving unparalleled military success that echoed through history? While the legendary discipline and tactical brilliance of their legions were undoubtedly fundamental, an equally crucial, though often less celebrated, factor was their mastery of advanced siege weaponry, particularly the catapult. These formidable machines were far more than simple projectile launchers; they stood as sophisticated instruments of destruction, capable of smashing fortifications, demoralizing enemies, and decisively altering the course of ancient battles. This article delves into the fascinating evolution of catapult technology, exploring its ingenious engineering, strategic deployment by the Romans, and the enduring legacy that fundamentally reshaped warfare for centuries. You can find more information on other Roman artifacts.

Engineering Marvels: The Catapult’s Evolution to Roman Dominance

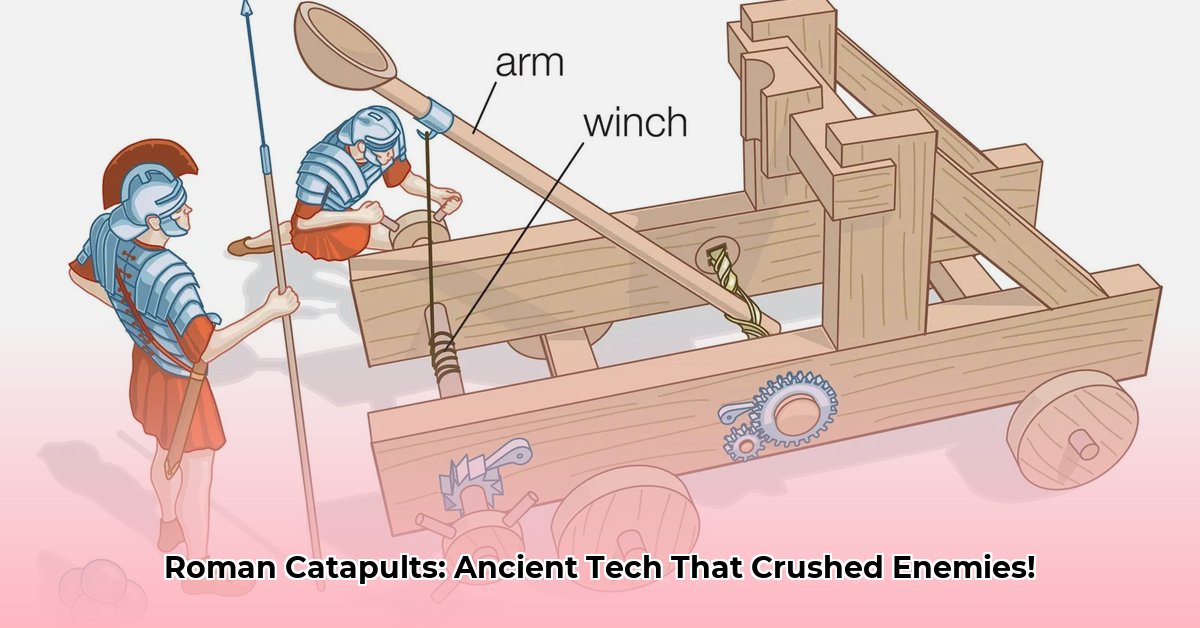

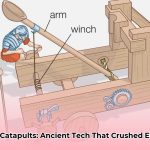

At its core, a catapult is a ballistic device designed to launch projectiles over significant distances without the aid of gunpowder. Instead, it harnesses immense stored potential energy, typically converting tension or torsion built up within the device before its sudden release. Long before the advent of gunpowder cannons, catapults could propel everything from heavy stones to incendiary materials. Yet, how did the Romans acquire and then elevate this ancient technology, transforming it into a definitive battlefield advantage?

The concept of a projectile-launching device predates Rome by many centuries. The earliest forms of catapults date to at least the 7th century BC, with King Uzziah of Judah reportedly equipping the walls of Jerusalem with machines that shot “great stones.” By the 5th century BC, the mangonel, a type of traction trebuchet, appeared in ancient China, later adopted by Ajatashatru of Magadha in India.

The true genesis of sophisticated catapult technology is intrinsically linked to the ancient Greeks. Around the early 4th century BC, Greek engineers invented mechanical arrow-firing catapults, attested by Diodorus Siculus as part of a Greek army’s equipment in 399 BC and swiftly employed at the siege of Motya in 397 BC. These primitive catapults were essentially attempts to increase the range and penetrating power of missiles by strengthening the bows that propelled them. Hero of Alexandria, drawing on the lost works of engineer Ctesibius, described the gastraphetes, or “belly-bow,” an early foot-held crossbow that inspired further innovation.

Crucially, from the mid-4th century BC onwards, evidence for the Greek use of arrow-shooting machines became denser. An Athenian arsenal inscription from 338-326 BC lists stored catapults with shooting bolts and springs of sinews, providing the first clear evidence for the switch to torsion catapults. These devices derived immense power from tightly twisted bundles of animal sinew or hair. This innovation likely emerged from the engineers of Philip II of Macedon, who, along with his son Alexander the Great, fully appreciated the strategic value of these machines, employing them in both ancient sieges and open-field engagements, fundamentally reshaping the dynamics of combat.

The Roman Touch: Innovation and Specialization

The Romans, renowned for their pragmatism and engineering acumen, were not content merely to replicate existing catapult designs. They meticulously refined them, prioritizing enhanced mobility, increased accuracy, and sheer destructive force. This strategic focus led to the development and widespread adoption of distinct Roman catapult types, each meticulously engineered for a specific tactical purpose, profoundly impacting their extensive military campaigns.

The Roman fascination with catapults deepened after observing Greek techniques, possibly after the Wars with Pyrrhus (280-275 BC). They took the Greek artillery weapons and improved them significantly, often making them smaller and more transportable while also developing larger, more powerful siege engines.

Key Roman Catapult Types: Precision and Devastation

- Scorpio: This smaller, highly accurate bolt-shooter derived its name from its “upraised sting” and was encased in a metal-plated box. With a range of around 100 meters (330 feet), the scorpio delivered deadly bolts at closer ranges, effectively serving as the “sniper rifle” of its era. Its compact size allowed for easy maneuvering and deployment in various combat scenarios, providing lethal precision targeting for anti-personnel use.

- Ballista: Resembling a colossal crossbow, the ballista was prized for its exceptional accuracy and versatility. It utilized torsion springs made from twisted ropes or animal sinew to propel large bolts or even stones. This exceptional precision allowed the Romans to target vulnerable points on a wall or pick off key enemy personnel. The term “ballista” itself would eventually give rise to the English word “ballistics.”

- Carroballista: This ingenious innovation seamlessly combined the power of a ballista with the mobility of a cart. This highly mobile artillery unit, featuring a metal frame and torsion springs of coiled rope or sinew, allowed for rapid deployment and repositioning across the battlefield, enabling adaptable fire support that was crucial for dynamic engagements.

- Onager: Named for the wild ass, celebrated for its powerful, kicking recoil, this formidable single-arm torsion machine hurled massive stones, often weighing up to 160 kilograms (350 pounds), with sufficient force to breach even the thickest fortress walls. Its name derived from the energetic bucking motion it exhibited upon firing. While not as accurate as the ballista, its strength lay in its unparalleled raw, unadulterated destructive power, making it the ultimate “sledgehammer” of Roman artillery for brute-force demolition. The Roman soldier and historian Ammianus Marcellinus vividly described its operation: “The onager’s framework is made out of two beams from oak… In the middle they have quite large holes… in which strong sinew ropes are stretched and twisted. A long arm is then inserted… at its end it has a pin and a pouch… When it comes to combat, a round stone… is put in the pouch and the arm is winched down. Then, the master artilleryman strikes the pin with a hammer, and with a big blow, the stone is launched towards its target.”

Julius Caesar’s masterful deployment of siege engines at the Battle of Alesia in 52 BC is often cited as a definitive moment, solidifying the Roman military’s reputation as unparalleled masters of siege warfare. His coordinated use of catapults and other fortifications demonstrated a profound strategic understanding, where continuous bombardment hindered Gallic reinforcements and demoralized the besieged. The ruthless efficiency of Roman artillery proved a significant factor in Caesar’s victory, cementing his reputation as a military genius. At the siege of Syracuse, Archimedes himself developed advanced artillery that could hurl “enormous stones” at Roman forces, supposedly weighing up to 1,800 pounds, demonstrating the extreme capabilities these machines could reach.

Construction, Operation, and Strategic Deployment

The construction of these complex Roman catapults was a monumental undertaking, demanding a combination of highly skilled craftsmen and meticulously sourced materials. Robust timber (primarily durable woods like oak and ash) formed the core framework, while resilient animal sinew (often from oxen or horses) was carefully prepared to form the incredibly powerful torsion springs. Additionally, specialized metal components, including iron and bronze, were forged for critical joints, armaments, and other mechanisms. Roman engineers continuously applied “design tweaks,” such as refining the onager’s sling for increased range or adding metal plates to the ballista’s arm for improved structural integrity, reflecting their dedication to engineering excellence.

Operating these machines was equally intricate, requiring dedicated, specialized teams meticulously trained in both the mechanical aspects of the devices and advanced military strategies. Each member had a specific role, from loading the projectiles to adjusting the tension for accurate firing. Coordinated efforts were essential, with teams working in unison to achieve a relentless barrage against enemy fortifications. For instance, an onager typically required a crew of eight soldiers. Decisions on when and where to unleash the catapults’ power could fundamentally turn the tide of battle, demonstrating the Romans’ mastery in integrating artillery into their comprehensive military tactics.

The sight and sound of a Roman catapult unleashing its payload had a profound psychological impact on enemy morale. As described by Josephus in his account of the siege of Jerusalem, “missiles from the engines flew over with such force that they reached the altar and the sanctuary, lighting upon priests and sacrificers… The dead bodies of natives and aliens, of priests and laity, were mingled in a mass, and the blood of all manner of corpses formed pools in the courts of God.” This relentless bombardment not only caused physical destruction but also crucially demoralized and broke the will of besieged troops, often contributing to faster surrenders.

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Materials & Construction | Primarily utilized robust, seasoned timber (such as oak and ash) for the main frame, ensuring structural integrity. Animal sinew (often from oxen, horses, or even women’s hair for optimal elasticity) formed the critical torsion springs, twisted with immense force. Iron and bronze were forged for mechanical components, reinforcement, and fittings, demonstrating Roman metallurgic prowess. Construction involved mortise and tenon joints, meticulous calibration, and continuous iterative ‘tweaks’ to enhance performance, based on years of empirical knowledge passed down. |

| Operation & Mobility | Required highly trained teams, often numbering eight soldiers for larger machines like the onager, for efficient loading, precise aiming, and powerful firing. Regular maintenance, including lubrication and tension adjustments, was paramount for optimal performance and longevity. Mobility varied significantly by type; the carroballista was highly mobile, mounted on carts for rapid battlefield deployment, whereas larger onagers and ballistae were often constructed on-site for extended sieges, requiring significant logistical support for transport and assembly. |

| Accuracy, Range & Impact | Ballistae were renowned for their pinpoint accuracy, capable of targeting specific personnel or weak points in fortifications from distances of 100 meters or more. Onagers prioritized raw power and widespread area damage, capable of hurling projectiles weighing hundreds of pounds, designed to batter down walls. Their range, dependent on size and type, allowed effective targeting of enemy fortifications and troop formations from a safe distance, while the visual and auditory spectacle of their operation had a profound psychological impact on enemy morale, often inducing panic and disrupting formations. This combination of physical destruction and psychological pressure was a key to Roman siege success. |

The Decline of the Catapult: An Arms Race Resolved

The Roman military catapult, an astonishing feat of ancient engineering principles, maintained its supremacy for several centuries. However, like all dominant technologies, its reign eventually concluded. The decline of catapults was not sudden but a gradual process driven by a relentless arms race between offensive and defensive military innovations.

The Rise of the Trebuchet

While Roman forces effectively utilized torsion-powered catapults, such as the ballista and onager, a powerful new contender emerged during the medieval period: the trebuchet. This represented a significant paradigm shift in siege technology. Instead of relying on twisted bundles of sinew for power, the trebuchet harnessed the immense, consistent power of gravity through a counterweight system. A massive counterweight on one end of a long arm would drop, propelling a projectile with incredible force from the other. This innovative design offered substantial advantages, including significantly increased range (sometimes over 400 meters) and raw power, making it capable of hurling much heavier projectiles than torsion engines. Some trebuchets could launch stones weighing several hundred pounds, or even use incendiary missiles like “Greek Fire.” While torsion catapults persisted, the trebuchet undeniably signaled a profound change in the trajectory of siege warfare, demonstrating superior efficiency and destructive capability.

Fortress Evolution

In this relentless technological arms race, fortifications underwent a dramatic evolution in direct response to the escalating destructive power of siege engines. Castle walls became substantially thicker, taller, and were ingeniously designed with defensive angles and layered defenses to better withstand sustained bombardment. The development of concentric castles, featuring multiple concentric layers of walls, made sieges increasingly arduous and protracted. While catapults could still inflict damage, defenders gained a much better chance of holding out against prolonged attacks, requiring ever larger and more powerful siege engines. This constant cycle of offensive and defensive innovation often defined the pace of military strategy throughout the medieval era.

Gunpowder Arrives: The Ultimate Obsolescence

The most decisive blow to the catapult’s long reign arrived with the groundbreaking introduction of gunpowder and, subsequently, cannons. Originating in China and arriving in Europe by the 14th century, early cannons, though initially crude, steadily improved in accuracy, range, and sheer destructive force. They possessed the capability to hurl projectiles with far greater velocity and impact than any catapult, and their relative ease of operation and lower maintenance requirements made them increasingly appealing. By the 15th century, cannons could effectively breach even the strongest medieval walls, rendering lengthy and resource-intensive sieges with catapults less necessary and strategically decisive. This marked a permanent and irreversible upheaval in military innovation, shifting warfare from mechanical torsion to explosive propulsion.

Shifting Military Tactics

As gunpowder weapons became more prevalent, military tactics fundamentally shifted. Armies could now achieve breaches in walls much more rapidly, rendering prolonged sieges less strategically decisive. The emphasis consequently moved towards dynamic open-field battles and agile maneuver warfare, where the cumbersome, less mobile catapults were significantly less effective compared to rapidly deployable artillery. The entire battlefield environment was transforming, and the heavy, fixed-position catapults struggled to adapt to this new, faster pace of combat. While the last large-scale army use of catapults was during the trench warfare of World War I, where they were briefly used to throw hand grenades across no man’s land before being replaced by small mortars, their role as primary siege weapons had long since ended.

The Enduring Legacy: Echoes Through Time

Despite their eventual fade from primary military use, catapults left an indelible mark on history that extends far beyond the Roman Empire. Their underlying engineering principles continued to influence the development of various other technologies, and they continue to captivate our imagination today. Even Renaissance polymath Leonardo da Vinci conceptualized improvements to catapult designs using leaf springs, illustrating their lasting engineering appeal.

The fundamental principles of catapults find surprising contemporary applications. Modern aircraft catapults are used to launch aircraft from naval carriers, particularly when takeoff areas are too short or to assist heavily loaded aircraft in becoming airborne. Early launched roller coasters also used catapult systems, later replaced by more advanced linear motors. The fascination with these ancient machines also endures in popular culture, from historical reenactments and museum exhibits to their portrayal in films, video games, and even competitive events like pumpkin chunking.

Dedicated historical reenactors meticulously reconstruct these magnificent machines, and museums globally utilize them as engaging exhibits to bring ancient history vibrantly to life. Educational projects and accessible DIY kits continue to foster interest in these remarkable Roman siege marvels among younger generations, providing a tangible connection to the past and offering a unique opportunity to understand the principles of physics and mechanics that the Romans mastered. Ongoing research and fascinating modern engineering applications continue to underscore the enduring genius of Roman catapult design. The compelling story of Roman catapults transcends a mere narrative of ancient weaponry. It is, at its core, a powerful testament to human ingenuity, relentless adaptation, and astute strategic thinking. Their undeniable impact on the trajectory of military history is paramount, and their profound legacy continues to inspire and inform engineers, historians, and enthusiasts alike. By deeply understanding the intricacies of their catapults, we gain an even richer appreciation for the formidable Roman military machine and its enduring, transformative influence on the entire course of history.

- Unlock ancient roman remedies: Natural treatments revealed for modern wellness. - August 17, 2025

- Unlock History: Ancient Roman Coin Necklace Trends & Buys - August 17, 2025

- Beyond Gladiators: Achievements in Ancient Rome Still Shaping Our World - August 17, 2025