From the relentless, disciplined march of its legions to the meticulous construction of its fortified camps, the Roman army stood as an unparalleled force in the ancient world. This wasn’t by mere chance; its enduring success was built upon a bedrock of iron discipline and a rigidly defined hierarchy where every soldier, from the newest recruit to the most seasoned general, understood their precise place, responsibilities, and purpose. This clear, intricate chain of command was the formidable engine that powered Rome’s vast conquests and maintained its sprawling empire for centuries. You can further explore the Roman army ranks for more details.

This comprehensive guide dissects the intricate professional structure of the Roman military, exploring the roles, responsibilities, daily lives, and pathways for advancement within the formidable Roman legionary system.

The Foundation: From Recruit to Seasoned Legionary

Every grand army begins with its most basic building blocks, and for Rome, these were the individual soldiers and their smallest unit formations.

Tirones: The Raw Recruits

Before earning the title of a true legionary, every new recruit began as a Tiro (singular) or Tirones (plural). For up to six demanding months, these raw recruits underwent rigorous training, transforming from civilians into disciplined warriors. Their regimen included endless drills with weapons twice the weight of standard issue, forced marches, trench digging, and constructing the palisade walls around nightly camps. This brutal training forged their physical strength, mental fortitude, and absolute obedience, preparing them for the harsh realities of military life.

The Munifex: The Common Legionary

Upon successful completion of their training, Tirones became Munifex – the basic private-level foot soldier. They constituted the vast majority of the Roman army, bearing the brunt of combat, daily labor, and camp duties. Their pay, while seemingly modest at around 900 sestertii annually, was further reduced by essential deductions for provisions like food, equipment, and clothing, often leaving them with only 300 to 400 sestertii. Despite this, the ultimate promise of Roman citizenship and a valuable plot of land upon retirement after 25 years of loyal service served as a powerful, life-changing incentive, offering a tangible pathway to social mobility and security unique to the Roman military.

Contubernium: The Tent Group

The absolute core of the Roman war machine lived and fought within the Contubernium. This smallest unit comprised eight men who shared a single tent or barracks room, their lives intricately intertwined. They cooked, ate, trained, and fought together, forging a bond of brotherhood where mutual reliance was paramount for survival. Overseeing this tight-knit group was a Decanus, typically the most experienced soldier among them, responsible for their immediate welfare and discipline.

Century & Cohort: The Core Battlefield Units

Ten Contubernia formed a Century, an 80-man unit commanded by a centurion. Six centuries then comprised a Cohort, totaling 480 fighting men. A standard Roman legion consisted of ten cohorts. However, the First Cohort was typically double-strength, composed of five centuries, each with 160 men, making it the elite unit of the legion, often positioned at the forefront of battle. This systematic organization allowed for flexible tactical deployment and ensured clear command.

The Backbone: Centurions and Non-Commissioned Officers (Principales)

If the legionaries were the muscle, the Centurions were the sinew, the vital link between high command and the foot soldiers. These were the grizzled, battle-hardened veterans who led their units from the very front.

Centurions: Leaders of Men

A Centurion was arguably the most famous and crucial rank in the Roman army, directly responsible for the discipline, training, and tactical execution of his 80 men in a century. With 59 centurions in a standard legion, their collective leadership was absolutely indispensable, often determining the success or failure of an engagement. These career officers rose through the ranks or were sometimes directly appointed, distinguishing themselves by wearing a transverse (side-to-side) crest on their helmet and carrying a vitis (vine staff) as a badge of office and a tool for administering corporal punishment. One infamous centurion, known as “Cedo Alteram” (“give me another”), earned his nickname for his habit of breaking his staff over his men’s backs and demanding a replacement.

Within the centurion ranks, a clear hierarchy existed:

* Primus Pilus (“First Spear”): The most senior and prestigious centurion in the entire legion. He commanded the first century of the elite First Cohort, which was double-strength (160 men), and served as a trusted advisor to the legion’s commander. Upon retirement, a Primus Pilus often gained entry into the equestrian social class, bridging the gap between the professional military and the Roman elite. This position offered significant social advancement and came with substantial pay, often around 60,000 sestertii.

* Primi Ordines: The five senior centurions of the First Cohort, including the Primus Pilus. They outranked all other centurions within the legion.

* Pilus Prior: Commanded the first century of a regular cohort and assumed command of the entire cohort in battle. Their pay could range from 15,000 to 30,000 sestertii depending on their duties and experience.

* Other centurions were ranked by their cohort and century, with diminishing prestige from the first cohort’s first century down to the tenth cohort’s sixth century.

The Principales: Non-Commissioned Officers

Beneath the centurions were the Principales, roughly equivalent to modern-day non-commissioned officers. These vital roles ensured the smooth day-to-day operations of the century:

- Optio: The centurion’s second-in-command, appointed from within the ranks. Stationed at the rear of the century during battle, the Optio ensured the men maintained formation and discipline, ready to take command if the centurion fell. They also assisted with administrative duties and training.

- Signifer: The standard-bearer of a century. He carried the signum, a spear-like standard decorated with medallions and often topped with an open hand symbolizing the oath of loyalty. This signum served as a crucial rallying point in the chaos of battle. The Signifer was also responsible for the century’s financial administration, including soldiers’ pay and savings. They were easily recognizable by the animal pelts they often wore as a badge of office.

- Tesserarius: The guard commander for the century, named after the tessera (wax tablet) on which daily passwords were kept. Responsible for organizing and overseeing guard duty, the Tesserarius also acted as a second-in-command to the Optio.

- Cornicen: The trumpeter of the century, who used a large bronze horn (cornu) to sound orders and convey commands across the din of battle, working closely with the Signifer.

- Aquilifer: The legion’s most prestigious standard-bearer, entrusted with carrying the Aquila, the golden eagle standard of the legion. Losing the Aquila was the ultimate disgrace for a legion. The Aquilifer was a highly experienced veteran and his position was typically a stepping stone to becoming a centurion.

- Imaginifer: Carried the imago, a special standard bearing the image of the reigning emperor, serving as a constant reminder of the legion’s loyalty to Rome and its leader.

Immunes: The Specialists

Beyond the fighting ranks were the Immunes, legionaries who possessed specialized skills and were therefore exempt (immunis) from common labor, guard duty, and menial tasks. This included engineers, architects, surgeons, blacksmiths, carpenters, surveyors, artillerymen, musicians, and clerks. Their expertise made them invaluable to the legion’s functionality, and they often received slightly higher pay. A Discens was an Immunis undergoing training in a specific craft.

Evocati: Recalled Veterans

Evocati were legionary veterans who had completed their term of service and earned their retirement but voluntarily chose to re-enlist, often in an advisory or specialist capacity. Their vast experience made them highly valuable assets to any legion.

The Officers: From Administration to High Command

Beyond the common soldiers and their immediate leaders, the Roman military hierarchy included several ranks of administrative and higher-ranking officers who orchestrated the legion’s large-scale operations and strategic movements.

Tribuni Angusticlavii: The Equestrian Tribunes

Each legion had five Tribuni Angusticlavii (narrow-stripe tribunes), drawn from the equestrian social class, a Roman order akin to landed gentry. Their roles were primarily administrative, managing the legion’s logistical operations, supplies, and paperwork. While they held some tactical command functions during engagements, their position was often a crucial first step in the cursus honorum (path of honor), a sequence of public offices for ambitious young men seeking to gain valuable military experience before pursuing full political careers in Rome.

Praefectus Castrorum: The Camp Prefect

Ensuring the legion’s survival and operational readiness rested heavily on the shoulders of the Praefectus Castrorum (“Camp Prefect”). This highly experienced veteran, typically a former Primus Pilus, was the ultimate logistician. He commanded the camp, oversaw its construction, maintenance, and overall management of the legion’s facilities. His technical expertise was indispensable for long-term campaigns, guaranteeing that troops were well-housed, protected, and supplied. The Camp Prefect was the third in command of a legion, taking over if the Legate was absent or unavailable.

Tribunus Laticlavius: The Senatorial Tribune

A fascinating, often paradoxical, position was that of the Tribunus Laticlavius (broad-stripe tribune). This was typically a young, high-born nobleman, often the son of a senator, appointed by the Emperor or Senate. Though he served as the second-in-command of the legion, he often held little direct command authority, especially compared to the seasoned Camp Prefect or even the equestrian tribunes. His presence in the legion served as a crucial apprenticeship, providing invaluable on-the-ground military experience and a deep understanding of army affairs, grooming him for future leadership roles in both the military and Roman politics.

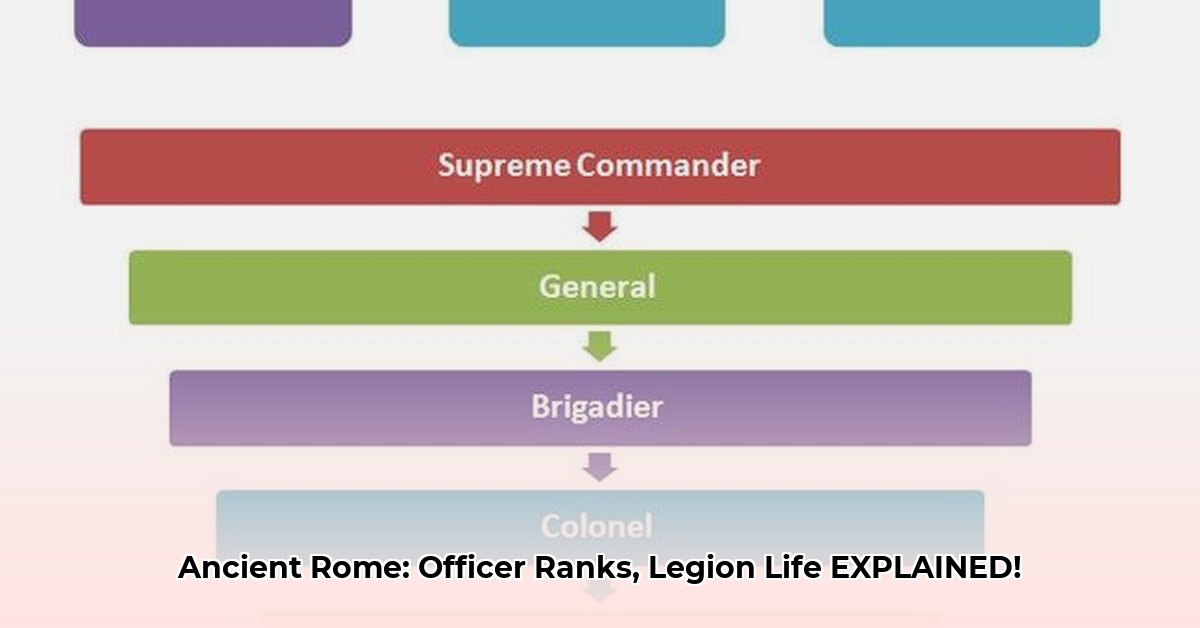

Legatus Legionis: The Legion Commander

Towering above them all in direct command of the fighting force was the Legatus Legionis, the commander-in-chief of an entire legion (typically 5,000-6,000 men). Appointed from the senatorial class, usually in his early thirties, the Legatus bore ultimate responsibility for everything: strategic planning, tactical decisions, troop discipline, and the overall well-being of his formidable force. His prestigious accommodations within the camp, known as the praetorium, often included luxuries befitting his senatorial status. In battle, his elaborate armor, crested helmet, and scarlet paludamentum (cloak) made him easily identifiable to his men. A Legatus typically held his post for three or four years, though longer stints were possible.

Legatus Augusti pro Praetore: The Imperial Governor

The highest military rank an officer could achieve was the Legatus Augusti pro Praetore, the military governor of an entire province. This commander held authority over multiple legions stationed within his province, in addition to his civilian governorship duties. These highly experienced senators combined extensive military and political careers, ensuring centralized control and efficient governance across vast territories of the Roman Empire.

The Essential Allies: Auxiliary Troops

No discussion of the Roman army’s might would be complete without acknowledging the Auxiliary Troops. These were non-citizen soldiers recruited from diverse parts of the Roman Empire, often bringing specialized skills that Roman legions lacked, such as expert archery (from Syria), superb cavalry maneuvers (from Gaul or Hispania), or light infantry tactics (from various barbarian tribes).

While auxiliary soldiers initially earned less than their legionary counterparts, their service came with an extraordinary incentive: full Roman citizenship upon completion of their 25-year enlistment. This promise was a powerful motivator, transforming non-citizens into loyal members of the Roman state and significantly broadening the empire’s military capabilities with diverse and specialized units.

Auxiliary units were organized differently from legions:

* Alae (Wings): Cavalry units typically consisting of 480 cavalrymen, divided into 16 turmae (squadrons), each commanded by a Decurion (around 30 troopers).

* Cohortes Auxiliares: Infantry cohorts, often mixed with cavalry, with ranks and positions mirroring those of legionaries, depending on the unit’s size and composition. Command of an auxiliary unit was typically held by a Praefectus Cohortis for infantry or a Praefectus Equitum for cavalry, usually from the equestrian class.

The Roman army’s unparalleled success wasn’t merely about brute force; it was a testament to its meticulously designed, highly structured, and adaptive organization. From the shared existence of the Contubernium to the strategic brilliance of the Legatus Legionis, every rank and role played a critical part in a cohesive, conquering machine. This intricate hierarchy, which offered opportunities for advancement, integrated diverse populations, and adapted to evolving military needs, epitomized Rome’s remarkable organizational genius. Now that you’re well-versed in the multifaceted ranks of the formidable Roman legion, you can truly appreciate the complexity behind their ancient might and enduring legacy.