Have you ever considered that clothing in ancient Rome was far more than mere covering? For women, attire served as a sophisticated visual language, meticulously communicating social standing, marital status, and adherence to deeply ingrained Roman societal values. This comprehensive guide delves into the intricate details of Roman women’s fashion, from the foundational garments to the luxurious materials and symbolic adornments, providing profound insights into their daily lives and societal roles. We’ll explore how Roman fashion subtly evolved over centuries, what different fabrics and styles signified, and even how ancient clothing techniques offer valuable lessons for today’s sustainable fashion. Get ready to discover how every thread and drape was a powerful statement for women in ancient Rome. Considering ancient Roman jewelry added to the statement.

Foundations of Roman Attire: Tunics, Stolas, and Public Identity

Ancient Roman women’s attire was fundamentally rooted in practicality, yet it evolved into a powerful communicative tool. Each garment, from the ubiquitous tunic to the distinctive stola and palla, contributed to a woman’s public identity and social narrative.

The Tunica: A Universal and Versatile Garment

The tunica served as the basic garment for all Romans, regardless of gender or social standing. Often likened to a simple dress or shirt, the tunica for women was characteristically ankle-length, providing full coverage. Unlike men’s tunics, which typically stopped at the knee, women’s versions often featured long sleeves, particularly for respectable married women, though short-sleeved or sleeveless variations also existed.

The material and craftsmanship of a tunica offered immediate social cues. While common citizens wore tunics of natural, undyed wool, wealthier women invested in finer, softer wools or lightweight linen, especially preferred during warmer months. For comfort and protection against the cold, women, like men, could wear a soft under-tunic or vest, known as a subucula, beneath a coarser outer layer. Historical accounts note that even Emperor Augustus, known for his delicate constitution, would layer up to four tunics over a vest in winter, underscoring the practical need for warmth.

Beyond the tunica, women also wore essential undergarments. Loincloths, called subligacula or subligaria, were common. Additionally, women wore a strophium or fascia pectoralis, a breast-wrap similar to a modern bra, for support. Archaeological discoveries, such as the 4th-century AD Sicilian mosaic depicting “bikini girls” performing athletic feats and a Roman leather bikini bottom excavated in London in 1953, offer compelling evidence of tailored underwear for work or leisure.

The Stola: Emblem of Matronly Virtue

For married Roman women, the stola was an indispensable garment, serving as the unequivocal symbol of their marital status and respectability. This long, sleeveless outer garment was typically suspended from the shoulders by straps or short sleeves and draped elegantly around the body, often reaching the feet. In the early Roman Republic, the stola was exclusively reserved for patrician women, but its use was later extended to plebeian matrons and even freedwomen who achieved matron status through marriage to a citizen. Wearing a stola publicly declared a woman’s married status, marking her as a virtuous and respectable member of Roman society; approximately 85% of married women in Roman society proudly wore this iconic garment. The stola typically consisted of two rectangular cloth segments joined at the sides by fibulae (brooches) and buttons, allowing the garment to fall in elegant, concealing folds.

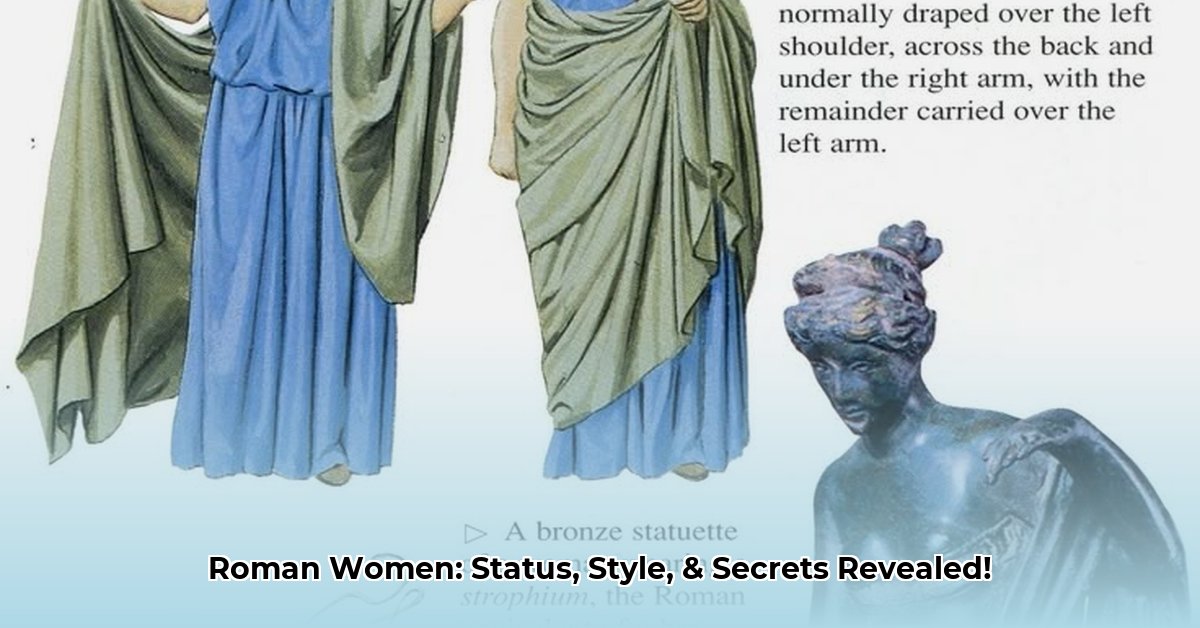

The Palla: Versatility and Modesty in Drapery

Accompanying the stola, the palla was a large, rectangular shawl, often measuring up to 11 feet long and 5 feet wide. This versatile garment could be draped over the stola in numerous configurations: worn as a coat, wrapped around the body, or pulled over the head to serve as a veil. Outdoors and in public, a chaste matron’s hair was often bound in woolen bands (fillets or vitae) in a high-piled style known as a tutulus, and her face was frequently concealed from the public gaze by her palla or a separate veil. Ancient literary sources mention the use of a colored strip or edging (limbus) on a woman’s mantle or tunic hem, likely a mark of high status, often rendered in prestigious purple. A matron appearing unveiled was considered to have repudiated her marriage. In stark contrast, high-caste women convicted of adultery and high-class female prostitutes (meretrices) were not only forbidden the public use of the stola but might have been compelled to wear a toga muliebris (a “woman’s toga”) as a public sign of their infamy.

Fabrics, Dyes, and Adornment: A Tapestry of Wealth and Status

The choice of textiles, the vibrancy of dyes, and the array of personal adornments spoke volumes about a Roman woman’s wealth, social standing, and aesthetic sensibilities. These elements formed a rich tapestry, reflecting the intricate social stratification of Roman society.

The Language of Textiles: From Wool to Silk

Wool was the most commonly used fiber in Roman clothing, available in qualities ranging from coarse to remarkably fine. Renowned wool from Tarentum, Miletus (Asia Minor), and Gallia Belgica supplied the empire. For most garments, white wool was preferred and often further bleached, while naturally dark wool was reserved for practical work garments or the toga pulla for mourning.

Linen, derived from flax and hemp, offered a lighter and more comfortable alternative to wool, especially suitable for warmer climates. The whitest and finest linen was imported from Spanish Saetabis, while the strongest came from Retovium. Natural linen had a “greyish brown” hue that faded to off-white with laundering and sunlight. It typically did not readily absorb the available dyes and was often bleached or used in its raw, undyed state.

Silk, imported from China as early as the 3rd century BC, was undoubtedly the most luxurious fabric. Raw silk was bought by Roman traders at Phoenician ports like Tyre and Berytus, then woven and dyed. As Roman weaving techniques advanced, silk yarn was used to create intricately figured damasks, tabbies, and tapestries, some exceptionally fine (over 50 threads per centimeter). The production of such highly decorative and costly fabrics was a specialty of weavers in the eastern Roman provinces. Sumptuary laws attempted to limit silk use; Seneca the Elder famously remarked on the perceived immodesty of silk garments: “I can see clothes of silk, if materials that do not hide the body, nor even one’s decency, can be called clothes… Wretched flocks of maids labour so that the adulteress may be visible through her thin dress, so that her husband has no more acquaintance than any outsider or foreigner with his wife’s body.” The importation and expenditure on silk represented a significant, inflationary drain on Rome’s gold and silver coinage. Diocletian’s Edict on Maximum Prices in 301 AD set the price of one kilo of raw silk at an astonishing 4,000 gold coins. Wild silk and rare sea silk, with its golden sheen from the Pinna nobilis clam, were also known.

Cotton, imported from India, was used for padding or woven into soft, lightweight fabrics ideal for summer. Unlike linen, cotton could be brightly dyed, and it was sometimes interwoven with linen to produce vibrant, durable fabrics. High-quality fabrics were also woven from nettle and poppy-stem fibers, producing glossy, smooth, and luxuriant textiles.

| Fabric | Primary Characteristics | Social Class Association | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wool | Varied qualities (coarse to fine), warm, durable. | All classes | Most common. Finer wools (Tarentum, Miletus) for wealthier. Used for everyday tunics, togas, cloaks. |

| Linen | Lightweight, breathable, comfortable in warmth. | Middle to Upper | Preferred for tunics in hot climates. Difficult to dye with available methods, often bleached or undyed. Quality varied by region. |

| Silk | Luxurious, soft, lightweight, delicate sheen. | Upper Class (Elite) | Imported from China, extremely expensive. Seen as a sign of decadence by conservatives. Significant economic impact due to drain on Roman coinage. |

| Cotton | Soft, lightweight, capable of bright dyeing. | Middle to Upper | Imported from India. More comfortable than wool in summer, less costly than silk. Sometimes interwoven with linen for color and texture. |

| Sea Silk | Rare, golden sheen, made from clam filaments. | Elite (Extremely Rare) | An exotic and exclusive luxury. |

| Nettle/Poppy | Glossy, smooth, lightweight. | Elite (Rare) | Specialty luxury fabrics, showcasing advanced textile techniques. |

The Power of Pigment: Dyes of Distinction

The Romans had access to a wide variety of colors, though some were far more prestigious and expensive than others. Tyrian purple, extracted from the murex sea snail, was the fastest, most expensive, and most sought-after dye. Its hues varied from deep red to a dark “dried-blood” red, and it was strongly associated with regality, divinity, and protection. Officially reserved for the border of the toga praetexta and the solid purple toga picta (worn by emperors and victorious generals), its casual use by wealthy women (and some men) was widely reported despite sumptuary laws. For those who could not afford genuine Tyrian purple, counterfeits, often using the dark blue of Indian indigo as a base, were available.

Other popular dyes included madder for various shades of red (one of the cheapest) and saffron yellow, which was costly, deep, and fiery, associated with purity and constancy. Saffron yellow was notably used for the flammeum, a distinctive veil worn by Roman brides and the Flaminica Dialis, Jupiter’s high priestess, symbolizing their virginity and unbroken marital bonds.

Beyond Garments: Adornment and Self-Expression

Roman women augmented their attire with an array of accessories, hairstyles, and cosmetics that further highlighted their status and personal style.

- Jewelry: Gold and silver jewelry gained popularity in the 1st century CE as the Empire expanded, providing access to precious metals and luxury objects. Roman jewelers, influenced by earlier Etruscan techniques like granulation and filigree, created intricate pieces. Precious stones, believed to have protective qualities (e.g., amethyst to relieve effects of overindulgence), became fashionable. Intaglio gems (gemmae), with carved images, were highly prized. Women of the elite amassed impressive collections; Pliny the Elder famously described Lollia Paulina, Emperor Caligula’s wife, covered in emeralds and pearls worth millions. Beyond necklaces, bracelets, rings, and earrings, women wore gold wire hairnets, diadems (tiaras), and elaborately decorated hairpins.

- Hairstyles: Unlike static clothing styles, Roman hairstyles changed frequently, serving as a reliable indicator for dating Roman art. Early Republican styles were simpler, focusing on chignons or rolled plaits, but by the Imperial era, influenced by empresses, elaborate curls, waves, and towering updos became fashionable. These intricate styles often required wire frameworks for height and frequently incorporated hairpieces and wigs, sometimes made from the hair of enslaved individuals. Wealthy women employed a specialized female slave, the ornatrix, for hairstyling, though hairdressing shops also existed. Tools like combs, tweezers, razors, and heated curling tongs have been discovered, similar to modern implements.

- Cosmetics and Perfume: Widely used by women and sometimes men, archaeological finds include pots with traces of blushers and face powders. The poet Ovid even penned Medicamina Faciei Femineae, a satirical guide to women’s beauty regimes, offering insights into ancient Roman beauty practices.

Even everyday objects like mirrors, found in abundance across the Empire, underscore the importance of personal appearance. For Roman women, clothing and adornments were not mere vanity but powerful symbols of social standing, personal achievement, and cultural identity.

Ancient Practices: How Romans Maintained Their Attire

Maintaining clean and presentable clothing was a considerable undertaking in ancient Rome, reflecting the high value placed on appearance and status. This necessity led to the development of a sophisticated, albeit unconventional, laundry industry.

The Societal Imperative of Cleanliness

In ancient Rome, a pristine appearance was intrinsically linked to an individual’s societal standing. The unwavering commitment to spotless garments was crucial for projecting an image of respectability and elevated status, particularly in urban settings where social interactions were frequent. This pervasive societal demand catalyzed the emergence of a specialized industry dedicated to garment care: the laundry business, overseen by skilled artisans known as fullones. For many Romans living in apartment blocks without personal laundry facilities, professional services were indispensable.

The Fullonicae: Rome’s Industrial Laundries

Envision a bustling workshop, alive with the sounds of splashing water and the rhythmic pounding of fabric: this was a fullonica, the ancient Roman counterpart to a modern industrial laundromat. These establishments provided comprehensive garment care services to Roman citizens, ensuring their clothing remained clean and presentable. But how did Romans clean clothes without modern detergents?

Ingenious Chemistry: The Role of Urine and Fuller’s Earth

In the absence of contemporary cleaning agents, Romans ingeniously harnessed readily available natural resources. Most notably, the ammonia content naturally present in aged urine acted as a potent cleaning agent, remarkably effective at breaking down dirt, grease, and stubborn stains. Fullers diligently collected urine from public restrooms and even accepted donations from passersby, underscoring its indispensable value. The fullonica of Stephanus in Pompeii, for instance, operated with an estimated capacity to clean hundreds of garments weekly.

The laundry process typically involved a series of methodical phases:

- Soaking and Agitation: Garments were immersed and vigorously agitated in large vats containing a mixture of water, aged urine, and various alkaline substances such as fuller’s earth (a natural clay, primarily montmorillonite, which absorbs oils and dirt). Fullers often physically stomped on the clothes with their bare feet to ensure thorough penetration and cleaning

- Unlock Ancient Roman Jewelry’s Secrets: History, Materials, & Symbolism Revealed - August 14, 2025

- Unveiling Ancient Roman Mythical Creatures: Legends, Powers & Origins Defined for Today’s Enthusiast - August 14, 2025

- Unlock Ancient Secrets: Ancient Roman Attire Women, Status, & Materials [Guide] - August 14, 2025