Have you ever paused to consider the profound, interwoven impact of ancient Greece’s “Golden Age” on our contemporary world? Imagine a transformative era, primarily flourishing across the 5th and 4th centuries BCE, where an explosion of innovation and intellectual prowess reshaped human civilization in unprecedented ways. This period marked a remarkable surge in creativity and groundbreaking ideas spanning philosophy, governance, arts, and sciences. We embark on a journey into this pivotal time to unravel its driving forces, understand its eventual conclusion, and illuminate its enduring relevance today. This exploration will bring into sharp focus the pioneering governmental structures, the visionary artists and thinkers, and the monumental historical events that forged this extraordinary epoch. Discover why the Golden Age of Greece remains an indispensable cornerstone of human achievement, resonating through millennia to influence the very fabric of our contemporary society. Want to explore more? See ancient Greece aesthetic.

The Dawn of a Golden Epoch: Defining the Classical Period

The ancient Greece Golden Age, often referred to as the Classical Period, predominantly centered in Athens, emerged from the crucible of the Persian Wars. Spanning roughly from 480 BCE to 323 BCE, culminating with the death of Alexander the Great, this era stands as a testament to human ingenuity and intellectual bravery. What truly defined this period was an unparalleled flourishing of culture, political innovation, and intellectual inquiry that laid foundational principles for Western civilization.

Forged in Conflict: The Genesis of Athenian Hegemony

The Persian Wars (499-449 BCE) were instrumental in catalyzing the ancient Greece Golden Age. These conflicts, particularly the decisive battles of Marathon (490 BCE), Thermopylae (480 BCE), and Salamis (480 BCE), not only repelled formidable external threats but also fostered an unprecedented, albeit temporary, sense of unity among the often-fractious Greek city-states. Athens, having distinguished itself through its naval power and strategic brilliance, emerged from these wars as the undisputed leader of the Hellenic world.

This newfound power led to the formation of the Delian League in 478 BCE, initially conceived as a mutual defensive alliance against future Persian aggression. However, under the shrewd leadership of statesmen like Themistocles and later Pericles, the League swiftly evolved into a de facto Athenian empire. Member states, numbering over 150, were compelled to contribute funds or ships to a treasury initially housed on the sacred island of Delos, which was later controversially moved to the Athenian Acropolis in 454 BCE. This immense influx of wealth provided the financial backbone for Athens’ extensive public projects, fueling an economic boom and providing widespread employment. The construction of iconic architectural marvels and the patronage of the arts were direct beneficiaries of this imperial expansion. Yet, this period of immense prosperity also planted the seeds of resentment among allied states, setting the stage for future conflicts.

Pillars of Innovation: Advancements That Shaped a Civilization

The Radical Experiment: Athenian Democracy

During the ancient Greece Golden Age, particularly in Athens, the radical concept of democracy was born and refined. Figures like Cleisthenes, with his reforms in the late 6th century BCE that broke the power of the aristocracy, and especially Pericles (c. 495–429 BCE), championed a system of direct citizen participation. This revolutionary model, where adult male citizens directly debated and voted on crucial legislative and policy matters in the Assembly (Ekklesia), marked a profound departure from earlier oligarchic or tyrannical forms of rule. The Boule (Council of 500), chosen annually by lot, managed daily affairs and prepared agenda for the Assembly, while the Dikasteria (popular courts) offered a jury system where citizens served as judges.

This direct participation fostered a robust sense of civic duty and collective ownership, cultivating a deeply engaged citizenry where reportedly at least 6,000 citizens regularly attended assembly meetings. However, it is crucial to acknowledge the inherent limitations of this system. Citizenship was strictly limited to adult males born to Athenian parents, systematically excluding women, enslaved individuals (who comprised a significant portion of the population), and resident foreigners (metics) from the political process. Can such a system, despite its groundbreaking nature, be considered fully democratic by contemporary standards of inclusivity? Its enduring legacy, nonetheless, fundamentally influenced the development of modern democratic ideals and systems worldwide.

Key Takeaways: How Democracy Flourished and Faced Limitations

- Athenian democracy, originating around the 5th century BCE, granted unprecedented civic power to its male citizens.

- Crucial democratic institutions included the Ekklesia (Assembly), the Boule (Council of 500), and the Dikasteria (popular courts).

- Direct citizen involvement constituted a central and defining principle of this governmental system.

- Citizenship was strictly limited to adult males of Athenian parentage, excluding a significant portion of the population.

- The Athenian democratic model significantly influenced the development of modern democratic ideals and systems.

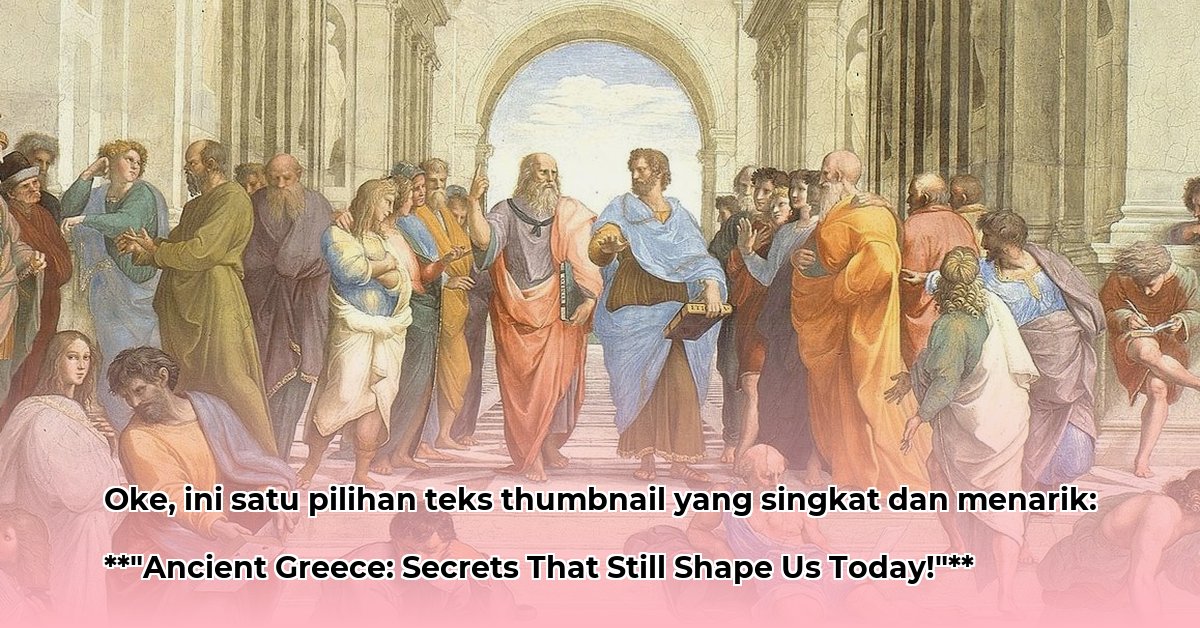

A Profound Shift in Thought: Philosophical Revolution

The ancient Greece Golden Age was a crucible for philosophical revolution, forever changing how humanity viewed existence, knowledge, and society. Trailblazing thinkers such as Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle delved deeply into ethics, epistemology (the study of knowledge), metaphysics, and political theory.

- Socrates (c. 470–399 BCE): Often hailed as the “father of Western philosophy,” Socrates famously employed his namesake method of questioning (elenchus) to challenge assumptions, expose contradictions, and promote rigorous self-examination. His focus on virtue, knowledge, and ethics, transmitted primarily through the writings of his students, laid the groundwork for moral philosophy. His refusal to compromise his principles, even unto death by hemlock, remains a powerful testament to intellectual integrity.

- Plato (c. 428–348 BCE): Socrates’ most illustrious student, Plato, founded the Academy in Athens, often considered the Western world’s first institution of higher learning. He developed a comprehensive system of philosophy, including his influential Theory of Forms, which posits that the physical world is merely a shadow of a higher, unchanging reality of perfect Forms. His works, particularly The Republic, explored ideal political systems, justice, and the nature of the soul, profoundly influencing political thought for millennia.

- Aristotle (384–322 BCE): Plato’s student, Aristotle, rejected the Theory of Forms, emphasizing empirical observation and logical reasoning. He established his own school, the Lyceum, and made foundational contributions to logic (the Organon), ethics (Nicomachean Ethics), politics, biology, physics, and poetics. His systematic approach to knowledge and categorization influenced scientific inquiry and educational curricula for centuries, earning him the title “the master of those who know” from Dante.

Their collective, profound insights continue to shape Western thought, academic inquiry, and ethical frameworks today.

Beauty in Stone and Sculpture: Artistic Masterpieces

Art and architecture reached unparalleled heights during the ancient Greece Golden Age, epitomizing the Greek pursuit of perfect balance, symmetry, and harmony.

- Architecture: The Parthenon (447–438 BCE), a magnificent Doric temple dedicated to the goddess Athena on the Athenian Acropolis, stands as the quintessential example of Greek architectural genius. Its precision in design, subtle optical refinements (such as entasis for columns), and harmonious proportions exemplify the “Golden Ratio.” Other architectural orders, the elegant Ionic and the ornate Corinthian, also found sophisticated expression in temples and public buildings across the Greek world, each contributing to a legacy that profoundly influenced subsequent Western architecture.

- Sculpture: Sculptors like Phidias (responsible for the Parthenon’s monumental cult statue of Athena Parthenos and its frieze), Polyclitus (known for his “Canon” of ideal human proportions and his Doryphoros), and Praxiteles (famed for introducing the fully nude female form with his Aphrodite of Knidos) infused their works with a remarkable blend of idealism and realism. They captured not only the idealized human form—especially the nude male athlete—but also profound human emotion and dynamic movement, employing techniques like contrapposto. These artistic principles, emphasizing proportion, anatomical accuracy, and aesthetic perfection, profoundly influenced subsequent artistic movements from the Roman Empire to the Renaissance and remain inspirational for artists and architects globally.

Beyond Philosophy and Art: Science, Mathematics, and History

The Golden Age also saw significant strides in other intellectual fields. Hippocrates (c. 460–370 BCE), often hailed as the “Father of Medicine,” revolutionized medical practice by moving away from superstition towards empirical observation and rational diagnosis. His ethical principles, encapsulated in the Hippocratic Oath, still underpin modern medical ethics. In mathematics, Pythagoras (though earlier, his influence peaked here) and Euclid (whose Elements codified geometry) laid fundamental groundwork. Historians like Herodotus (c. 484–425 BCE), the “Father of History,” recorded the Persian Wars, and Thucydides (c. 460–395 BCE), known for his rigorous, objective account of the Peloponnesian War, set new standards for historical inquiry and political analysis.

The Crucible of Conflict: When Things Started to Fall Apart

The Peloponnesian War: A Costly Downfall

The mounting tensions between Athens and Sparta, exacerbated by Athens’ imperial ambitions and its heavy-handed treatment of Delian League members, finally erupted into the devastating Peloponnesian War (431-404 BCE). This protracted and brutal conflict, meticulously documented by Thucydides, severely depleted Athens’ human and material resources. A devastating plague (likely typhus) ravaged Athens in 430 BCE, claiming the life of Pericles himself, and significantly weakening the city.

The war starkly exposed critical flaws in Athenian strategy, particularly its over-reliance on naval power, which proved insufficient against Sparta’s formidable land forces and the eventual intervention of Persia on Sparta’s side. Notable blunders, such as the disastrous Sicilian Expedition (415–413 BCE), led to catastrophic losses of ships and men. Moreover, the war intensified internal political divisions within Athens, as factions fiercely competed for control, leading to periods of oligarchy and instability. The war culminated in Athens’ defeat, the dismantling of its empire, and the installation of a pro-Spartan oligarchy known as the Thirty Tyrants, marking a profound end to its political golden age.

External Threats and Shifting Power: The Rise of Macedonia and Rome

Following the Peloponnesian War, while Athens did experience a partial recovery and philosophical life continued to flourish, its political and military dominance was irreversibly broken. A power vacuum emerged, and no single Greek city-state could achieve lasting hegemony. This instability would eventually pave the way for a formidable external power: Macedonia.

The ascent of Macedonia, first under the brilliant military strategist Philip II (r. 359–336 BCE), and then his legendary son, Alexander the Great (r. 336–323 BCE), fundamentally reshaped the regional balance of power. Through a combination of military innovation and diplomatic skill, Philip II gradually subjugated the Greek city-states, culminating in the Battle of Chaeronea (338 BCE), which effectively ended Greek independence. Alexander the Great’s subsequent conquests across Persia, Egypt, and India, while spreading Hellenistic culture far and wide, also cemented the end of the city-state era and thus the Golden Age of an independent Greece.

Centuries later, the burgeoning Roman Empire emerged as the preeminent Mediterranean power. Through a series of wars between the 2nd and 1st centuries BCE, Rome gradually conquered and incorporated Greece into its vast dominion, largely completing the process by 146 BCE with the destruction of Corinth. The decline of Athens, and indeed of the independent Greek city-states, was ultimately an inevitable outcome of shifting geopolitical landscapes and the rise of larger, more unified empires.

The Enduring Legacy: Echoes of the Golden Age in the Modern World

Despite its eventual political decline, the ancient Greece Golden Age bequeathed an enduring, profound legacy that continues to shape the very fabric of Western civilization. Its foundational ideas on democracy, philosophy, art, literature, and science continue to resonate deeply within our contemporary society. This era serves as a powerful, timeless testament to humanity’s boundless capacity for creativity, intellectual curiosity, and rigorous inquiry.

Studying this period provides invaluable lessons that extend far beyond historical facts. It offers fundamental insights into the complexities of self-governance, the necessity of critical thinking, the pursuit of profound knowledge, and the essence of the human condition itself. The wisdom gleaned from this incredible period remains strikingly relevant, making its influence palpable in our institutions, our art, and our intellectual pursuits today.

Core Insights from the Golden Age of Greece:

- Athens emerged as a beacon of unprecedented flourishing in democracy, philosophy, and artistic expression.

- The Persian Wars propelled Athens’ ascent, while the Peloponnesian War proved a critical factor in its eventual decline.

- The profound legacy of this era continues to influence Western thought, governmental structures, and artistic principles, shaping our world today.

Practical Takeaways: Applying Ancient Wisdom Today

| Who’s Involved | Short-Term Ideas (This Year) | Long-Term Thinking (3-5 Years) |

|---|---|---|

| Educators | Leverage excerpts from seminal works by Plato (e.g., Allegory of the Cave) and Thucydides (History of the Peloponnesian War) to encourage deep analytical thinking and debate among students on enduring societal questions. | Develop interdisciplinary curricula that explicitly connect ancient Greek achievements—in political theory, philosophical inquiry, architectural design, and dramatic arts—to their observable manifestations and transformations in modern politics, urban planning, and artistic expression. |

| Government Leaders | Analyze historical case studies of successes and failures within Athenian democracy to inform policy discourse and enhance decision-making frameworks regarding civic participation and governance models. | Commission comprehensive studies on the rise and decline of the Golden Age, focusing on socio-political dynamics and systemic vulnerabilities, to derive actionable insights for fostering sustainable societal growth and resilience in contemporary nations. |

| Artists & Designers | Integrate principles of Greek classical art, such as emphasis on proportion, harmony, and idealized forms, into contemporary design projects to elevate aesthetic appeal and structural integrity, as demonstrated by their lasting impact on architectural masterpieces worldwide. | Engage in philosophical exploration of the underlying values and humanistic ideals embedded in Greek art, utilizing these insights to inform the creation of art that transcends mere aesthetics, expressing profound ideas and cultural values relevant to the human experience today. |

How Did Athens Decline? A Detailed Examination

Key Takeaways:

- Athens’ downfall resulted from internal democratic challenges, imperial overreach through the Delian League, and external pressures from rivals like Sparta and, later, Macedonia and Rome.

- The Peloponnesian War was a significant catalyst, draining Athenian resources and exacerbating internal strife and political instability.

- Athens’ transformation of the Delian League into an empire fostered widespread resentment among its member states and drew the ire of other Greek powers.

- The emergence of Macedonia and the subsequent rise of the Roman Empire ultimately ended Athenian political dominance and the era of independent Greek city-states.

The Self-Inflicted Wounds of Democracy: A Double-Edged Sword

Could the very strength of Athens’ direct democracy have paradoxically led to its weakening and eventual decline? Some scholars propose that while empowering citizens, this system became unwieldy and susceptible to the fluctuating sentiments of popular opinion as Athens’ empire expanded. Unlike today’s representative democracies, Athenian citizens directly participated in decision-making, which, while revolutionary for its time, posed challenges for consistent, informed deliberation on complex state affairs. For instance, were all citizens adequately equipped to debate intricate military strategies or nuanced foreign policy, sometimes leading to impulsive or ill-advised decisions under the sway of charismatic but often unscrupulous demagogues? The ostracism of capable leaders like Themistocles and the tragic execution of Socrates highlight the darker side of direct democracy when consensus faltered or emotions ran high.

The Perils of Imperial Ambition: The Delian League’s Transformation

Athens’ preeminent role in the Persian Wars positioned it to lead the powerful Delian League. Initially conceived as a mutual defense pact, this alliance rapidly morphed into an Athenian-dominated empire. Member states were compelled to provide increasingly heavy financial contributions (phoros) and military support; Athens ruthlessly suppressed any attempts at secession or non-compliance, notably against Naxos and Thasos. This heavy-handed approach cultivated deep resentment and opposition among its supposed allies. The vast wealth extracted from the League was funneled into Athens, financing its magnificent building programs like the Parthenon and its powerful navy, which in turn solidified its control. Did the profound allure of imperial power corrupt Athens, guiding it down a path of aggressive expansion that ultimately alienated its allies and provoked its rivals?

The Peloponnesian War: A Cataclysmic Conflict

The mounting tensions and irreconcilable ideological differences between democratic Athens and oligarchic Sparta finally erupted into the devastating Peloponnesian War (431-404 BCE). This prolonged and exceptionally brutal conflict severely depleted Athens’ human and material resources. The devastating plague that swept through Athens in 430 BCE, claiming a quarter to a third of its population, including Pericles, significantly weakened the city’s resolve and leadership. The war starkly exposed critical flaws in Athenian strategy, particularly its over-reliance on naval power, which proved insufficient against Sparta’s formidable land forces and its eventual alliance with Persia. The disastrous Sicilian Expedition (415–413 BCE), an ill-conceived attempt to expand Athenian power into the Western Mediterranean, resulted in the loss of thousands of men and hundreds of ships, dealing an irreversible blow to Athenian strength. Moreover, the war intensified internal political divisions within Athens, as factions fiercely competed for control, leading to periods of oligarchy (like the Thirty Tyrants) and profound instability. The eventual defeat in 404 BCE, marked by the destruction of its long walls and the loss of its empire, signaled the definitive end of Athens’ dominant role in the Greek world.

External Threats: The Rise of Macedonia and the Roman Hegemony

Even if Athens had successfully navigated its internal challenges and the Peloponnesian War, formidable external threats loomed. The subsequent ascent of Macedonia, first under the militarily brilliant Philip II and then his legendary son, Alexander the Great, fundamentally reshaped the regional balance of power. The once-dominant Greek city-states, weakened by internal strife and incessant warfare, were simply no match for the centralized might and innovative military tactics of the Macedonian kingdom. Philip II systematically conquered or subjugated most of Greece, culminating in the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BCE, which effectively ended the era of independent Greek city-states. Alexander’s subsequent vast empire, while spreading Hellenistic culture globally, also marked the end of the Classical Period and the traditional Golden Age.

Later, the burgeoning Roman Empire emerged as the preeminent Mediterranean power. Through a series of conflicts, particularly the Macedonian Wars, Rome gradually asserted its dominance over Greece. By 146 BCE, with the destruction of Corinth, Greece was formally incorporated as a Roman province. The decline of Athens’ political and military might was thus ultimately an inevitable outcome of both internal struggles and shifting geopolitical landscapes where larger, unified empires supplanted the fragmented power of city-states.

The Enduring Cultural and Intellectual Legacy

Despite its political and military decline, the cultural and intellectual influence of Athens and the broader Golden Age of Greece persisted for centuries and continues to shape the very fabric of Western civilization. Its profound contributions to philosophy, literature, art, and architecture laid critical foundations for Western thought and aesthetics, enduring far beyond the fleeting political power of the city-state. The Parthenon remains a timeless symbol, and the philosophical inquiries of Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle continue to be debated and applied in contemporary academic and ethical discourse. While its empire waned, Athens’ legacy as a pivotal center of learning, innovation, and civic ideals endures as a beacon of human potential.

Proven Artistic – Philosophical Advancements in the Golden Age

Key Takeaways:

- The Golden Age of Greece, particularly Athens, was a crucible for significant advancements in democracy, philosophy, art, and science, profoundly influencing Western civilization.

- Athenian democracy, while pioneering in its direct citizen involvement, notably excluded women, enslaved people, and foreigners from political participation.

- Seminal philosophers, including Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle,

- Unearth ancient rome achievements: Engineering feats & legal legacies, examined - August 13, 2025

- Unlock ancient rome army ranks: Power, impact & legion command - August 13, 2025

- Conquer Your Exam: Ancient Greece Quiz Ace It Now! - August 13, 2025