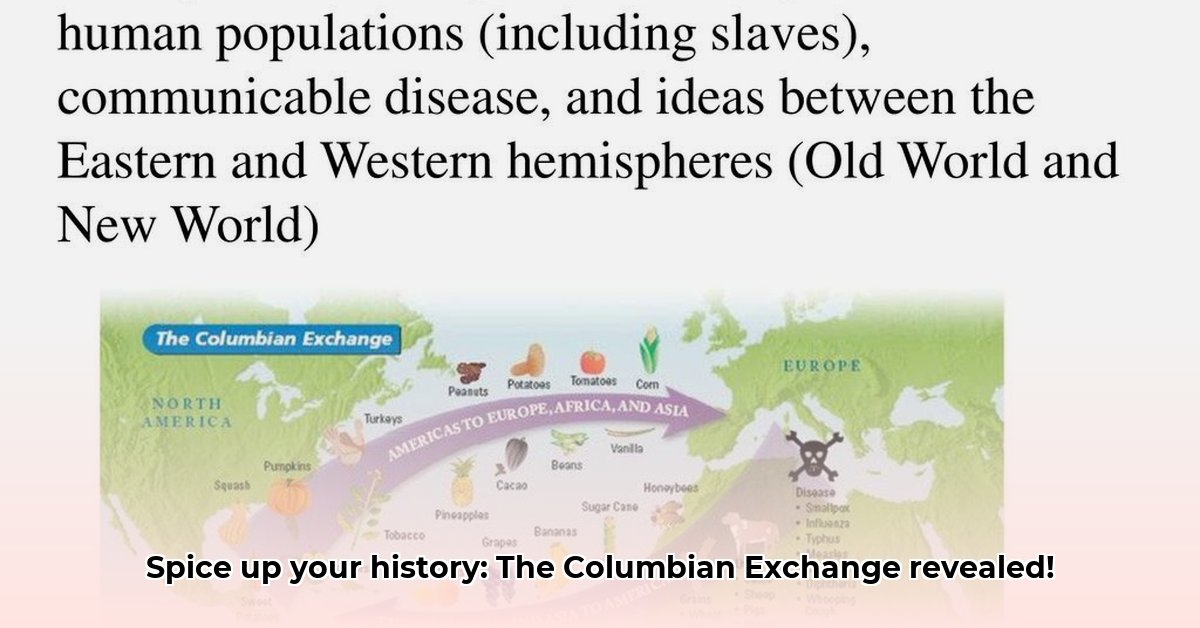

Ever wondered why Italian pasta has tomatoes, or Irish stew has potatoes? It’s all thanks to a massive food swap that happened after Columbus’s voyages! For another example of historical trade impacting food, see this article on ancient Egyptian rations. The Columbian Exchange, beginning in 1492, fundamentally changed what we eat around the world. This wasn’t just about trading a few spices – it was a transformative exchange of plants, animals, and cultures. This article explores that amazing culinary journey, revealing how everyday ingredients have incredibly interesting histories tied to this pivotal event. We’ll examine how foods traveled across continents, how cultures adapted to new ingredients, and how the Exchange continues to influence our plates today. Get ready for a flavorful trip through history!

The Columbian Exchange: A Culinary Revolution in Global Food Systems

Imagine Italian cuisine without tomatoes or Irish meals without potatoes. These ingredients, now fundamental to their respective cultures, were once foreign. The Columbian Exchange, the widespread transfer of plants, animals, foods, and cultures between the Old World (Europe, Africa, and Asia) and the New World (the Americas) following Christopher Columbus’s 1492 voyage, revolutionized diets, economies, and culinary traditions across the globe, creating a food landscape that still shapes our meals today.

A Recipe for Global Change: The New World’s Contributions to Culinary Traditions

When Spanish and Portuguese explorers first arrived in the New World, they were introduced to an abundance of new plants and food sources cultivated by the Indigenous civilizations of the Aztecs, Maya, and Inca. These foods had been domesticated and perfected over thousands of years, forming the backbone of Mesoamerican, Andean, and Amazonian diets. European conquerors and settlers, at first reluctant to embrace Indigenous crops, soon realized their incredible nutritional value, adaptability, and economic potential. Over the next few centuries, these foods would spread across Europe, Asia, and Africa, becoming essential to global diets and economies.

Perhaps the most influential of all New World crops was the potato. Native to the Andean highlands of present-day Peru and Bolivia, potatoes were a staple food of the Inca Empire, capable of thriving in harsh mountainous conditions. When Spanish explorers brought potatoes back to Europe in the 16th century, they were first regarded as a curiosity, grown only in botanical gardens. However, as famine and food shortages swept across Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries, the potato’s ability to grow in poor soil and provide high caloric yields made it an indispensable staple crop. In Ireland, Germany, and Russia, it became a dietary mainstay, fueling population booms and even shaping historical events—most notably, the Irish Potato Famine (1845–1852), which led to mass emigration and economic collapse.

Another game-changing crop was the tomato, originally cultivated by the Aztecs in Mexico and known as xitomatl. Spanish explorers brought tomatoes back to Spain and Italy, where they were initially met with suspicion, as some Europeans believed they were poisonous due to their resemblance to deadly nightshade plants. Over time, tomatoes became a defining ingredient in Mediterranean cuisine, giving rise to iconic dishes like pasta with tomato sauce, Spanish gazpacho, and French ratatouille. Without the introduction of the tomato, Italian cuisine as we know it today would not exist.

Equally transformative was the chili pepper, which originated in Central and South America and was domesticated thousands of years ago by Indigenous civilizations. Spanish and Portuguese traders quickly realized its value as a cheap and potent alternative to black pepper, a luxury spice that had to be imported from Asia at great cost. The chili pepper spread rapidly along trade routes, reaching India, China, Thailand, and Korea by the late 16th century. Today, it is impossible to imagine Indian curries, Sichuan cuisine, or Korean kimchi without the fiery heat of the chili pepper—a crop that didn’t exist in Asia before 1492.

Then there was cacao, the sacred “food of the gods” among the Aztecs and Maya, who consumed it as a bitter, spiced drink. When Spanish conquistadors encountered cacao, they were unimpressed at first, but after mixing it with sugar and cinnamon, it became one of the most sought-after luxuries in European courts. By the 17th and 18th centuries, chocolate was a staple of French and Spanish aristocracies, and its cultivation in the Caribbean and West Africa would fuel centuries of plantation economies and global trade. Today, Swiss, Belgian, and French chocolates are world-renowned, but their origins lie in the cacao groves of Mesoamerica.

Other crops, like maize (corn), beans, peanuts, and vanilla, also found their way into global food cultures, reshaping diets and economies across Africa, Asia, and Europe. In China, sweet potatoes and maize became essential to feeding growing populations, while in West Africa, peanuts and cassava (brought from South America via Portuguese traders) became key ingredients in local stews and porridges.

The New World’s contribution to global food was nothing short of revolutionary. These crops did not just supplement Old World diets—they fundamentally reshaped them, giving rise to new dishes, new industries, and even new empires built on the backs of these newfound agricultural riches. Today, the influence of these foods remains undeniable—whether in a bowl of spicy Thai curry, a plate of Italian pasta, or a bar of chocolate, the legacy of the Columbian Exchange continues to be tasted in every corner of the world.

Europe’s Culinary Gifts (and Unintended Consequences: Diseases and Demographic Shifts)

While New World foods such as potatoes, tomatoes, and chili peppers transformed European, Asian, and African diets, the Columbian Exchange also brought Old World crops to the Americas, reshaping Indigenous agriculture and daily life in profound ways. The introduction of wheat, rice, sugarcane, bananas, citrus fruits, and coffee revolutionized food production across the Spanish, Portuguese, French, and British colonies, laying the foundation for plantation economies, colonial trade networks, and lasting culinary traditions that persist in the Americas today.

Before 1492, the Indigenous peoples of the Americas cultivated a diverse range of staple crops, such as maize (corn), beans, squash, and cassava. However, many Old World grains and fruits were completely unknown in the Americas. When European colonists arrived, they sought to recreate familiar diets from home, introducing crops that would fundamentally alter the agricultural landscape of the New World. Some of these crops thrived, becoming essential staples that would later define Latin American, North American, and Caribbean cuisines.

One of the most significant Old World crops introduced to the Americas was wheat. Before Spanish colonization, Indigenous Americans did not cultivate wheat—their staple grains were maize and quinoa. However, the Spanish viewed wheat as a symbol of civilization and Christianity, believing that it was superior to maize. Hernán Cortés and his men planted the first wheat fields in Mexico in the early 1500s, and within decades, wheat production spread across the Andes, Central America, and North America.

By the 17th century, wheat had become a staple crop in Mexico, Argentina, and the American Southwest, giving rise to European-style breads, pastries, and tortillas de harina (flour tortillas). Today, Argentinian empanadas, Mexican bolillos, and Cuban pan suave all have their roots in Spanish wheat cultivation.

Rice, originally domesticated in China and West Africa, was introduced to the Americas by Spanish and Portuguese traders. While the Spanish brought Asian rice varieties to Mexico, Peru, and the Caribbean, the Portuguese introduced West African rice to Brazil, where it became a crucial part of the diet.

Rice quickly became a staple food for enslaved Africans working on plantations and merged with local ingredients to create iconic Creole, Brazilian, and Caribbean dishes. In Louisiana and South Carolina, enslaved West Africans used Old World rice to develop dishes like jambalaya, while in Brazil, the fusion of rice and beans became the national dish, feijoada.

Perhaps no Old World crop had a greater economic impact on the Americas than sugarcane. Originally cultivated in India and the Mediterranean, sugarcane was introduced to the Caribbean and Brazil by Spanish and Portuguese colonists in the early 1500s. The warm, humid climate of the region was perfect for sugar production, leading to the rise of massive sugar plantations that would define the economies of the Caribbean and South America for centuries.

Along with sugar, bananas and citrus fruits (oranges, lemons, limes) were introduced by the Spanish and Portuguese in the 16th century. Bananas, which originated in Southeast Asia and Africa, were brought to the Caribbean, Central America, and Brazil, where they flourished in tropical climates. Over time, bananas became a staple of Latin American and Caribbean diets, featuring prominently in dishes like tostones (fried plantains), banana-based stews, and desserts like Brazilian banana fritters.

Although coffee originated in Ethiopia and was cultivated in Arabia and the Ottoman Empire, it wasn’t until the Spanish and Portuguese introduced it to the Americas in the 17th century that it became one of the most valuable global commodities.

Brazil, in particular, became a coffee powerhouse, as its climate was ideal for coffee cultivation. By the 19th century, Brazil had become the largest coffee exporter in the world, fueling European and North American demand for caffeine. Today, Colombian, Brazilian, and Caribbean coffee remain some of the most prized varieties globally, showing the lasting impact of Old World agriculture on New World economies.

The introduction of Old World crops to the Americas forever altered Indigenous diets, colonial economies, and modern food traditions.

While the Columbian Exchange brought new foods, animals, and agricultural techniques to the New World and beyond, it also fueled one of the most devastating and inhumane systems in world history: the transatlantic slave trade. The demand for cash crops like sugar, tobacco, and cotton in European markets created an insatiable need for labor, and the Indigenous populations of the Americas, ravaged by European diseases, war, and forced labor, proved unable to meet the demands of the colonial economy. As a result, European powers—particularly Spain, Portugal, Britain, France, and the Netherlands—turned to the African slave trade to supply a seemingly endless workforce for their growing empires.

While the Columbian Exchange is often celebrated for its culinary and agricultural impact, one of its most devastating consequences was the spread of deadly diseases from the Old World to the New World. The introduction of smallpox, measles, influenza, and other European illnesses decimated Indigenous populations across the Americas, leading to the collapse of entire civilizations. This biological exchange was one-sided—while some European and African diseases spread rapidly in the New World, very few American illnesses made their way back to Europe with the same level of devastation.

Before 1492, the Indigenous peoples of the Americas had never been exposed to Old World diseases. Because they had lived in relative isolation for thousands of years, they lacked immunity to the pathogens that had circulated in Europe, Asia, and Africa for centuries. Meanwhile, Europeans, Africans, and Asians had coexisted with domesticated animals like cows, pigs, and chickens, which were responsible for spreading diseases such as smallpox, influenza, and tuberculosis. Over time, Old World populations developed some resistance to these illnesses, but Indigenous Americans had no previous contact with these pathogens, making them extremely vulnerable.

The effect of Old World diseases on the Americas was nothing short of catastrophic. In the first 100 years following Columbus’s arrival, up to 90% of the Indigenous population in some regions perished due to disease alone.

A Two-Way Street with a Bitter Aftertaste: Colonization, Power Imbalances, and Cultural Transformation

The Columbian Exchange was more evenhanded when it came to crops. The Americas’ farmers’ gifts to other continents included staples such as corn (maize), potatoes, cassava, and sweet potatoes, together with secondary food crops such as tomatoes, peanuts, pumpkins, squashes, pineapples, and chili peppers. Tobacco, one of humankind’s most important drugs, is another gift of the Americas, one that by now has probably killed far more people in Eurasia and Africa than Eurasian and African diseases killed in the Americas.

Some of these crops had revolutionary consequences in Africa and Eurasia. Corn had the biggest impact, altering agriculture in Asia, Europe, and Africa. It underpinned population growth and famine resistance in parts of China and Europe, mainly after 1700, because it grew in places unsuitable for tubers and grains and sometimes gave two or even three harvests a year. It also served as livestock feed, for pigs in particular.

In Africa about 1550–1850, farmers from Senegal to Southern Africa turned to corn. Today it is the most important food on the continent as a whole. Its drought resistance especially recommended it in the many regions of Africa with unreliable rainfall.

The durability of corn also contributed to commercialization in Africa. Merchant parties, traveling by boat or on foot, could expand their scale of operations with food that stored and traveled well. The advantages of corn proved especially significant for the slave trade, which burgeoned dramatically after 1600. Slaves needed food on their long walks across the Sahara to North Africa or to the Atlantic coast en route to the Americas. Corn further eased the slave trade’s logistical challenges by making it feasible to keep legions of slaves fed while they clustered in coastal barracoons before slavers shipped them across the Atlantic.

Cassava, or manioc, another American food crop introduced to Africa in the 16th century as part of the Columbian Exchange, had impacts that in some cases reinforced those of corn and in other cases countered them. Cassava, originally from Brazil, has much that recommended it to African farmers. Its soil nutrient requirements are modest, and it withstands drought and insects robustly. Like corn, it yields a flour that stores and travels well. It helped ambitious rulers project force and build states in Angola, Kongo, West Africa, and beyond. Farmers can harvest cassava (unlike corn) at any time after the plant matures. The food lies in the root, which can last for weeks or months in the soil. This characteristic of cassava suited farming populations targeted by slave raiders. It enabled them to vanish into the forest and abandon their crop for a while, returning when danger had passed. So while corn helped slave traders expand their business, cassava allowed peasant farmers to escape and survive slavers’ raids.

The potato, domesticated in the Andes, made little difference in African history, although it does feature today in agriculture, especially in the Maghreb and South Africa. Farmers in various parts of East and South Asia adopted it, which improved agricultural returns in cool and mountainous districts. But its strongest impact came in northern Europe, where ecological conditions suited its requirements even at low elevations. From central Russia across to the British Isles, its adoption between 1700 and 1900 improved nutrition, checked famine, and led to a sustained spurt of growth.

Eurasian and African crops had an equally profound influence on the history of the American hemisphere. Until the mid-19th century, “drug crops” such as sugar and coffee proved the most important plant introductions to the Americas. Together with tobacco and cotton, they formed the heart of a plantation complex that stretched from the Chesapeake to Brazil and accounted for the vast majority of the Atlantic slave trade.

Introduced staple food crops, such as wheat, rice, rye, and barley, also prospered in the Americas. Some of these grains—rye, for example—grew well in climates too cold for corn, so the new crops helped to expand the spatial footprint of farming in both North and South America. Rice, on the other hand, fit into the plantation complex: imported from both Asia and Africa, it was raised mainly by slave labour in places such as Suriname and South Carolina until slavery’s abolition. By the late 19th century these food grains covered a wide swathe of the arable land in the Americas. Beyond grains, African crops introduced to the Americas included watermelon, yams, sorghum, millets, coffee, and okra. Eurasian contributions to American diets included bananas; oranges, lemons, and other citrus fruits; and grapes.

The Columbian Exchange, and the larger process of biological globalization of which it is part, has slowed but not ended. Shipping and air travel continue to redistribute species among the continents.

A Legacy Still Served on Our Plates: Sustainable Food Systems and Global Cooperation

The Columbian Exchange was the single most influential food migration in human history, shaping the way nations eat, farm, and trade food. While we may take it for granted today, every meal we consume—whether a bowl of pasta, a spicy curry, or a bar of chocolate—bears the imprint of this centuries-old exchange. It was a process driven by exploration, conquest, and exploitation, yet it also led to some of the most celebrated culinary traditions in the world. Without it, modern food as we know it simply wouldn’t exist.

The next time you sip a cup of coffee, enjoy a plate of tacos, or bite into a juicy tomato, remember—you are experiencing the legacy of a centuries-old global exchange that forever altered the history of food. The Columbian Exchange didn’t just change the world—it built the global food culture we live in today.

The Columbian Exchange continues to leave its mark. Our globalized world, filled with a delicious variety of foods, owes its culinary diversity, in part, to this transformative event. However, understanding the full picture – both its benefits and its devastating consequences – is crucial for building a fairer, more sustainable food future.

Key Ingredients of Change: A Culinary Timeline and Nutritional Impact

Here’s a glimpse of some pivotal exchanges and their impact—it’s just a small sample of the vast transformations that occurred:

| From the Americas | To the Americas | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Potatoes, Tomatoes, Maize | Wheat, Rice, Sugarcane | Became dietary staples globally; transformed agriculture. |

| Chili Peppers, Cacao | Livestock (horses, cattle, pigs) | Revolutionized cuisines; altered farming and nutrition. |

| Sweet Potatoes, Beans | Diseases (smallpox, measles) | Devastating demographic impact; societal restructuring; loss of Indigenous farming knowledge; introduction of forced labor. |

How did the Columbian Exchange impact specific regional cuisines long-term?

The Columbian Exchange reshaped agricultural landscapes and culinary traditions by introducing New World crops to Europe and European crops to the Americas. Due to their higher caloric yields, New World staples, particularly potatoes, became integral to European diets. They fostered culinary innovations, leading to dishes such as mashed potatoes and modern French fries. Conversely, European crops like wheat, barley, and grapes significantly impacted indigenous populations, introducing new food sources while sidelining traditional crops. Wheat became a staple for bread, and grapes facilitated wine production, altering agricultural practices.

The Americas: A Culinary Crossroads

Before European contact, the Americas boasted a rich diversity of crops—maize, potatoes, beans, tomatoes, peppers, squash—that formed the foundation of sophisticated Indigenous cuisines. The arrival of Europeans introduced Old World staples like wheat, rice, sugarcane, and livestock. This wasn’t a simple swap, however. The introduction of these “new” crops often led to displacement of traditional foodways and created reliance on European models of food production.

Europe: A New Palette

Europe experienced a culinary transformation. The introduction of potatoes, tomatoes, maize, and chili peppers revolutionized European cuisine. The potato, initially met with skepticism, became a dietary cornerstone across the continent, fueling population growth and shaping culinary traditions for centuries. Tomatoes, initially considered ornamental, eventually became a vital ingredient in Italian and Mediterranean cuisine. The introduction of new spices and crops also spurred culinary innovation and experimentation.

Asia: Spices and New Staples

The Columbian Exchange also had a profound effect on Asian cuisines. The introduction of chili peppers added a new dimension to the flavors of South and Southeast Asian dishes, while sweet potatoes and maize became crucial staples in some regions. The exchange was, however, largely a one-way street; the flow of crops and ingredients was significantly more pronounced from the Americas to Asia.

Africa: A Legacy of Forced Migration

The impact of the Columbian Exchange on Africa is inextricably linked to the transatlantic slave trade. Africans were forcefully migrated to the Americas, where they brought with them their culinary traditions and adapted to new ingredients within a system of brutal oppression.

A Lasting Legacy: Understanding the Past, Shaping the Future

The Columbian Exchange’s legacy continues to shape our world. The crops introduced during this historical period remain fundamental to global diets. However, understanding its complex history—the exploitation, the disease, and the cultural shifts—is crucial. It reminds us of the interconnectedness of food systems, the importance of biodiversity, and the need to build more equitable and sustainable food practices for the future.

Columbian Exchange Impact on Indigenous American Diets and Agriculture

The Columbian Exchange dramatically expanded the variety and diversity of global cuisine, reshaping culinary traditions and diets across continents. New foods, ingredients, and cooking methods from different regions fused together, impacting how people cooked and ate. This exchange laid the groundwork for global food systems, with effects that continue to be felt today.

A Two-Way Street

The Columbian Exchange wasn’t one-sided. Both hemispheres saw a dramatic influx of new species. The Americas received wheat, barley, rice, sugarcane, horses, cattle, pigs, sheep, and chickens. Europe, Asia, and Africa gained maize (corn), potatoes, tomatoes, beans, squash, tobacco, and cacao. Imagine the culinary revolution! Suddenly, European diets were enriched with potatoes, fundamentally changing their nutritional landscape and supporting population growth.

Disease: A Silent Killer

While new crops offered possibilities, Old World diseases proved catastrophic for Indigenous populations. Smallpox, measles, influenza, and typhus ravaged communities, decimating entire societies. These diseases, to which Indigenous people lacked immunity, resulted in massive population decline, disrupting established agricultural systems and profoundly impacting food production and distribution.

Reshaping the Landscape

The introduction of European farming techniques and crops alongside the devastation caused by disease dramatically altered traditional agricultural practices. The rise of plantation economies, particularly in the Caribbean and parts of South America, focused on cash crops like sugar, often at the expense of food production for local populations and employing enslaved African labor. This fundamentally altered the food systems and land usage.

A Legacy of Change

The Columbian Exchange Impact on Indigenous American Diets and Agriculture is complex. While new foods enriched global diets, the social and environmental ramifications were severe. Even today, the influence of the Columbian Exchange remains, shaping our food systems and the very landscapes we inhabit. We can’t truly understand our current food landscape without grasping its profound legacy.

The Columbian Exchange and the Transformation of European Cuisine

The Columbian Exchange dramatically altered global diets, introducing previously unknown ingredients and agricultural techniques across continents. This historical exchange fostered cultural diffusion, significantly transforming food production, transportation, and trade dynamics. The introduction of crops like potatoes and commodities such as cocoa and sugar enriched diets, increased variety, and contributed to evolving gastronomic landscapes. Moreover, these shifts influenced economic practices and sparked demographic changes, as the increase in calorie-rich crops led to population growth.

A World Transformed

Imagine a world without tomatoes in pasta sauce, potatoes in your fries, or chocolate in your candy. Hard to picture, isn’t it? That’s the power of the Columbian Exchange. This wasn’t just a simple trade; it was a biological and cultural earthquake that reshaped the very essence of what we eat. Started by Columbus’s voyages, it unleashed a torrent of plants, animals, and agricultural techniques between the Old and New Worlds.

New World Bounty

The impact on Europe was profound. Suddenly, previously unknown ingredients flooded the market. The humble potato, originally from the Andes, became a dietary mainstay, fueling population growth and even inspiring culinary revolutions. Spicy chilies added zest to European dishes, changing the flavor profiles of countless regional recipes.

This explosive influx of New World ingredients wasn’t just a culinary adventure; it also generated new economic opportunities and trade routes. The demand for these coveted products reshaped global commerce, creating new empires and economic power structures. The implications of this economic boom were complex, leading to both prosperity and exploitation.

A Two-Way Street

However, the Columbian Exchange wasn’t a one-sided affair. While Europe benefited enormously, the New World also underwent a significant transformation. Old World crops like wheat and sugarcane, along with livestock such as cattle and pigs, profoundly altered agricultural landscapes and dietary habits in the Americas. Yet this often came at a tremendous cost.

A Legacy of Inequality

The devastation caused by Old World diseases on Indigenous populations is a stark reminder of the profoundly unequal nature of the exchange. The introduction of smallpox, measles, and other ailments decimated entire communities, leading to a catastrophic collapse of pre-existing social structures and agricultural knowledge. The Columbian Exchange and the Transformation of European Cuisine must therefore grapple with these dark realities, exploring the complex legacy of exploitation and cultural disruption alongside the culinary innovations.

Looking Toward the Future

The echoes of the Columbian Exchange reverberate even today. The global food system, despite its complexity, is still largely shaped by the patterns of exchange established centuries ago. We now face new challenges—sustainable agriculture, food security, and equitable distribution. Understanding the history of the Columbian Exchange is not merely an academic exercise; it is essential to crafting a more just and sustainable food future.