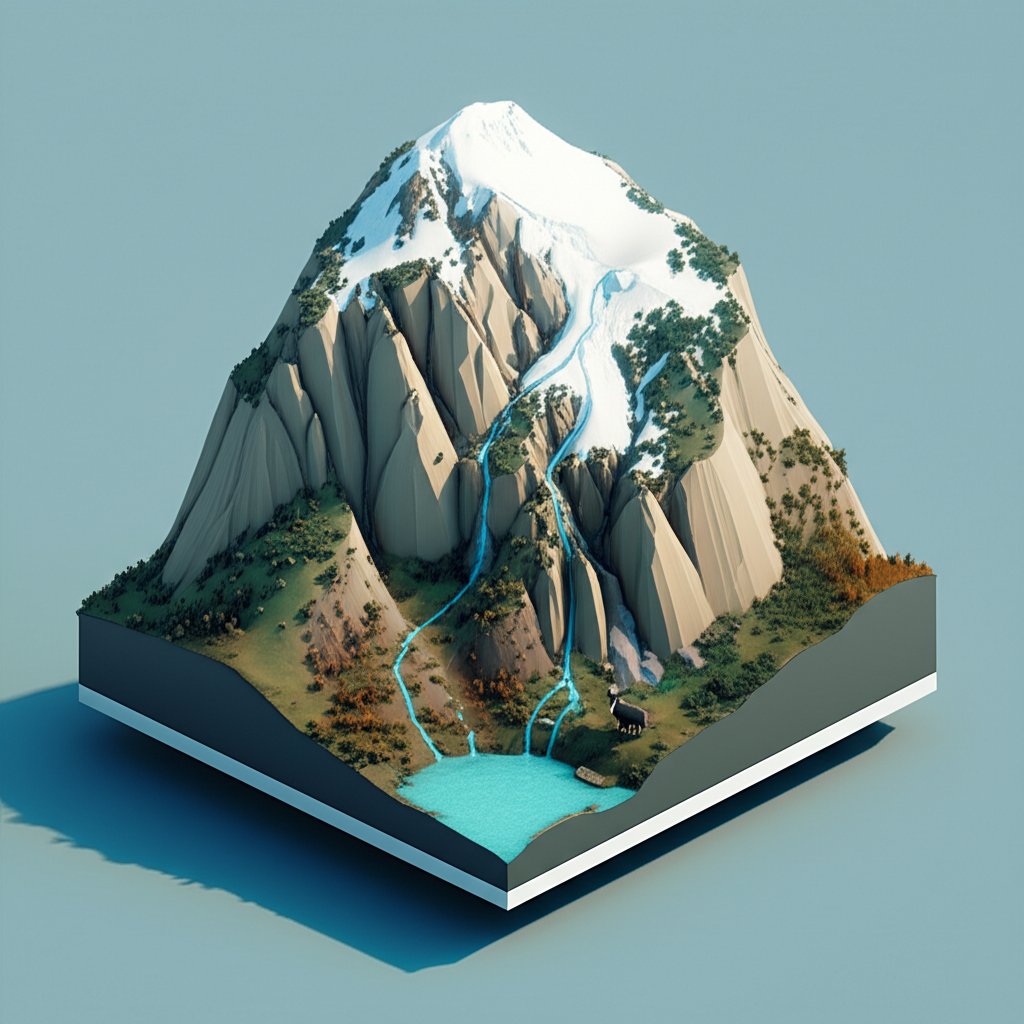

Nestled at the roof of the world, alpine ecosystems represent some of Earth’s most breathtaking and unique natural environments. These “islands in the sky,” characterized by extreme altitudes, harsh climates, and specialized biodiversity, are critical components of global mountain ecosystems. However, these incredibly fragile habitats are facing an unprecedented crisis, driven relentlessly by the dual forces of climate change and habitat loss. This comprehensive article delves into the intricate challenges threatening these vital alpine biomes, exploring their profound ecological significance and the urgent need for collective action to prevent their irreversible decline.

Unveiling Alpine Ecosystems: Earth’s Fragile High-Altitude Realms

Alpine ecosystems are extraordinary natural laboratories, home to life forms uniquely adapted to survive where few others can. They are more than just cold, rocky peaks; they are vibrant, though often subtle, tapestries of life. Understanding their defining characteristics is the first step toward appreciating the scale of the threats they face.

Defining the Alpine Biome: Above the Treeline

The alpine biome is broadly defined by its elevation above the natural treeline, where trees give way to low-growing, cold-tolerant vegetation. This transition zone is shaped by incredibly harsh environmental conditions:

Geographically, alpine ecosystems are found across the globe’s major mountain ranges, including the European Alps, the North American Rockies, the vast Himalayas, the Andes, and the Southern Alps of New Zealand. Each region harbors its own distinct assemblage of species, showcasing the incredible adaptability of life. Specialized plants, from cushion-forming sedges and grasses that hug the ground for warmth, to vibrant wildflowers that burst into bloom during the short summer, define these landscapes. Animals, such as the elusive snow leopard, the agile ibex, the vigilant marmot, and the iconic pika, have evolved intricate survival strategies, including thick fur, hibernation, and highly efficient metabolisms.

The Ecological Significance of Mountain Ecosystems

Beyond their intrinsic beauty, mountain ecosystems – and their higher-altitude alpine components – provide invaluable ecological services that benefit billions of people worldwide. Often referred to as “water towers of the world,” mountains are the source of most major rivers, supplying freshwater for drinking, agriculture, energy generation, and industry.

Moreover, these regions are critical biodiversity hotspots. Their varied topography, climate gradients, and isolated nature have fostered the evolution of a disproportionately high number of endemic species – species found nowhere else on Earth. They also play a crucial role in regulating global climate patterns, influencing atmospheric circulation and carbon cycling. The health of these mountain ecosystems is thus inextricably linked to the well-being of the planet as a whole.

The Accelerating Scourge of Climate Change on Alpine Biomes

Climate change is arguably the most pervasive and insidious threat to alpine ecosystems, pushing them beyond their natural adaptive limits. Due to their altitude and often high latitude, these regions are experiencing warming at rates significantly faster than the global average, leading to a cascade of ecological disruptions.

Rapid Warming and Glacial Retreat

The most visible sign of climate change in the mountains is the dramatic retreat of glaciers and permanent snowfields. As temperatures rise, the delicate balance between snow accumulation and melt is skewed, resulting in a net loss of ice mass. This isn’t just an aesthetic concern; it has profound hydrological consequences.

- Altered Water Cycles: Glaciers act as natural reservoirs, slowly releasing meltwater during dry periods. Their disappearance or significant reduction alters the timing and volume of water flow, leading to increased runoff and flooding initially, followed by severe water scarcity in downstream communities and ecosystems.

- Permafrost Thaw: Many alpine biomes feature permafrost – ground that remains frozen for at least two consecutive years. Rising temperatures are causing this permafrost to thaw, destabilizing mountain slopes, leading to increased landslides, rockfalls, and mudflows. This also releases stored carbon and methane, creating a dangerous feedback loop that exacerbates global warming.

Examples abound, from the shrinking glaciers in the European Alps, which have lost up to 50% of their volume since 1900, to the rapid disappearance of ice in the tropical Andes, threatening water supplies for millions.

Upslope Migration and Species Extinction Risk

As temperatures warm, species adapted to cooler conditions are forced to shift their ranges to higher altitudes, a phenomenon known as “upslope migration” or “altitudinal squeeze.” However, mountains are finite. Eventually, species simply run out of space, pushed off the top of the “sky islands.” This leads to:

- Habitat Compression: The total area of suitable cold habitat shrinks, intensifying competition among species and increasing their vulnerability.

- Phenological Mismatches: Warming temperatures can cause earlier snowmelt or changes in plant flowering times, disrupting the finely tuned relationships between plants and their pollinators or herbivores. A pika, for instance, might rely on certain grasses for its winter cache, but if those grasses flower and senesce earlier, its food source could be jeopardized.

- Increased Extreme Weather Events: Beyond gradual warming, climate change amplifies the frequency and intensity of extreme weather. More intense storms can cause localized flooding and erosion, while prolonged droughts stress water-dependent plants and animals, increasing fire risk in subalpine zones.

Altered Hydrology and Water Scarcity

The change in snowpack duration and melt timing is a critical impact. A reduced snowpack means less water stored for the spring and summer. Earlier melt means that water is available sooner, but may run out before the peak growing season or critical human demand, leading to:

- Drought Conditions: Even if total precipitation remains constant, changes in its form (less snow, more rain) and timing can lead to summer droughts.

- Impact on Aquatic Ecosystems: Alpine lakes and streams, which are often nutrient-poor and highly sensitive to temperature fluctuations, suffer from reduced flow, increased water temperatures, and altered oxygen levels, threatening unique aquatic life.

- Downstream Supply: Communities and agricultural systems far removed from the mountains often depend entirely on consistent glacial or snowmelt. Disruptions here have widespread socio-economic consequences.

Habitat Loss and Fragmentation: Eroding the Foundations of Alpine Life

While climate change is a global force, localized habitat loss and fragmentation represent direct, physical assaults on alpine ecosystems. These threats are often interconnected, with human development both directly destroying habitat and exacerbating climate impacts.

Expansion of Human Footprint and Infrastructure

The allure and resources of mountains draw human activity, leading to an ever-expanding footprint that directly consumes and fragments critical alpine biomes.

- Urbanization and Development: As towns and cities expand in alpine valleys, they encroach upon surrounding natural areas. This urbanization brings with it increased demand for land, water, and resources, leading to the conversion of natural habitats into developed areas.

- Tourism and Recreation Infrastructure: Ski resorts, hiking trails, cable cars, and related facilities directly destroy vegetation, compact soils, and disrupt wildlife. While providing economic benefits, uncontrolled tourism can lead to significant degradation.

- Roads and Transportation Networks: The construction of roads and railways carves through sensitive landscapes, acting as impenetrable barriers for wildlife. These networks not only destroy habitat directly but also introduce noise, air pollution, and human disturbance, further fragmenting landscapes. Experts, including those at the World Wildlife Fund, consistently highlight that extensive transportation infrastructure is a leading cause of habitat fragmentation, significantly impeding the movement and survival of alpine species.

- Mining and Resource Extraction: Resource-rich mountain regions are often targets for mining, which involves large-scale land disturbance, deforestation, and the generation of toxic waste, devastating local ecosystems and contaminating water sources.

Unsustainable Land Use Practices

The way we manage mountain lands has a profound impact on their ecological integrity.

- Intensive Agriculture and Grazing: Traditional, low-impact farming in mountain valleys is increasingly replaced by intensive agricultural practices. This can lead to soil degradation, increased runoff of pesticides and fertilizers into alpine streams, and the conversion of biodiverse natural grasslands into monocultures. Overgrazing by livestock can strip vegetation, compact soil, and exacerbate erosion, especially on steep slopes.

- Deforestation: While high alpine ecosystems are naturally treeless, the subalpine and montane forest zones below them are crucial. Deforestation for timber, fuel, or land conversion removes protective forest cover, leading to soil erosion, reduced water retention, and increased risk of landslides and avalanches. This also destroys critical habitat for species that move between forest and alpine zones.

The Invisible Walls: Fragmentation’s Impact on Biodiversity

Habitat fragmentation is more than just habitat loss; it’s the process by which large, continuous habitats are broken into smaller, isolated patches. This has devastating consequences for biodiversity:

- Genetic Isolation: Small, isolated populations have reduced genetic diversity, making them more vulnerable to disease, inbreeding, and less able to adapt to environmental changes.

- Disrupted Movement: Roads and developed areas become “invisible walls,” preventing animals from accessing essential resources like food, water, and mates, or from following traditional migration routes. This is particularly problematic for wide-ranging species.

- Edge Effects: The boundaries between natural and disturbed habitats (edges) experience altered microclimates, increased predation, and invasion by non-native species, reducing the effective size of remaining habitat patches.

- Increased Human-Wildlife Conflict: As wildlife is confined to smaller areas, encounters with humans and livestock become more frequent, often leading to conflict and further population declines.

The Pervasive Threat of Pollution in High Altitudes

Despite their remote appearance, alpine ecosystems are far from immune to pollution. Both locally generated and globally transported pollutants pose significant threats, often accumulating in these cold environments.

Atmospheric Deposition and its Cascade Effects

Air pollution, originating from industrial centers, vehicular exhaust, and agricultural emissions, can travel vast distances carried by global wind patterns, eventually depositing onto remote mountains.

- Acidification: Emissions of sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides lead to acid rain and dry deposition, acidifying sensitive alpine soils and water bodies. This harms aquatic life and alters nutrient cycling, impacting plant health.

- Heavy Metal Accumulation: Heavy metals, such as mercury and lead, released by industrial processes, can accumulate in alpine snow, ice, and soils. As these metals enter food webs, they can bioaccumulate, reaching toxic levels in predators.

- Nitrogen Deposition: Excess nitrogen, primarily from agriculture and fossil fuel combustion, acts as a fertilizer in nutrient-limited alpine soils. While seemingly beneficial, it can alter competitive dynamics among plant species, promoting fast-growing generalists over rare, slow-growing alpine specialists, thus decreasing biodiversity.

Local Pollution from Tourism and Development

The very activities that draw people to the mountains also contribute to pollution.

- Waste and Litter: Unmanaged waste from tourism, settlements, and recreational activities pollutes the landscape, harms wildlife, and can leach toxins into soils and water.

- Wastewater: Inadequate wastewater treatment in mountain communities can contaminate rivers and streams, altering their ecological balance and posing health risks.

- Noise Pollution: Constant noise from vehicles, machinery, and human activity can disrupt wildlife behavior, leading to stress, altered foraging patterns, and reduced reproductive success.

- Microplastics: Emerging research reveals microplastic contamination in even the most remote alpine environments, carried by wind and snow, posing unknown long-term risks to ecosystems.

Guardians of Global Health: Why Protecting Mountain Ecosystems is Crucial

The crisis facing alpine ecosystems is not merely an environmental concern; it represents a threat to global ecological stability and human well-being. Their protection is paramount for several interconnected reasons.

Biodiversity Hotspots and Endemic Species

As highlighted earlier, mountain ecosystems are reservoirs of biodiversity, hosting more than 85% of the world’s amphibians, birds, and mammals, and a significant proportion of its plant species. Their unique conditions have fostered an extraordinary degree of endemism. The loss of a single alpine species due to habitat loss or climate change means the loss of an irreplaceable part of Earth’s biological heritage, with potential cascading effects throughout the food web. These genetic resources hold unexplored potential for medicine, agriculture, and scientific understanding.

Essential Ecosystem Services

The services provided by mountain ecosystems are fundamental to life on Earth:

- Water Supply: Mountains are the primary source of freshwater for a significant portion of the global population. Their snow and ice packs, along with their forests and wetlands, regulate water flow, purify water, and prevent floods.

- Climate Regulation: Mountain forests and soils act as carbon sinks, storing vast amounts of carbon dioxide. Healthy alpine biomes contribute to global climate stability.

- Soil Stabilization and Hazard Prevention: Mountain vegetation and stable soils prevent erosion, landslides, and avalanches, protecting downstream communities and infrastructure. The thawing of permafrost and loss of vegetation exacerbates these natural hazards.

Cultural and Recreational Value

Beyond their ecological and hydrological importance, mountains hold immense cultural, spiritual, and recreational value. For centuries, indigenous communities have lived in harmony with mountain environments, developing unique cultural practices and traditional ecological knowledge. Today, mountains offer unparalleled opportunities for recreation, spiritual reflection, and connection with nature, contributing significantly to human health and well-being. The degradation of these landscapes diminishes not only natural capital but also cultural heritage and quality of life.

Pathways to Preservation: Solutions for the Alpine Crisis

While the challenges are formidable, the future of alpine ecosystems is not predetermined. A multi-faceted approach involving global cooperation, local action, and individual responsibility can lead to effective preservation and restoration.

Mitigating Climate Change: Global and Local Actions

Addressing the root cause of the Alpine Ecosystems Crisis requires urgent and ambitious action on climate change.

- Global Emissions Reduction: Transitioning away from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources, improving energy efficiency, and reducing emissions across all sectors (industry, transport, agriculture) are fundamental. International agreements and national policies must be strengthened and enforced.

- Carbon Sequestration: Protecting and restoring mountain forests, peatlands, and soils can enhance their natural ability to absorb and store carbon.

- Climate Adaptation: For unavoidable impacts, communities and ecosystems must adapt. This includes developing early warning systems for natural hazards, implementing water management strategies to cope with altered water cycles, and fostering climate-resilient agriculture.

Sustainable Land Management and Conservation Efforts

Protecting alpine biomes from habitat loss and other direct pressures requires thoughtful land use and dedicated conservation.

- Establishment and Management of Protected Areas: Designating and effectively managing national parks, nature reserves, and wilderness areas is crucial for safeguarding critical habitats and biodiversity. These areas need to be resilient to climate change.

- Ecological Connectivity: Creating and maintaining ecological corridors that link fragmented habitats allows species to move and adapt to changing conditions, promoting gene flow and population resilience.

- Responsible Tourism and Development: Implementing strict environmental guidelines for mountain tourism and infrastructure development, promoting eco-tourism, and engaging visitors in conservation efforts can minimize negative impacts. Prioritizing sustainable agriculture and forestry practices in mountain regions is also key.

- Restoration Projects: Actively restoring degraded alpine habitats, such as reforesting deforested slopes or rehabilitating polluted streams, can help revive ecosystem functions and biodiversity.

Policy, Research, and Community Engagement

Effective conservation relies on a robust framework of policies, scientific understanding, and active participation.

- International Cooperation: Transboundary cooperation, such as the Alpine Convention, is essential for managing shared mountain ranges and addressing cross-border environmental issues. Similar agreements are needed for other major mountain ecosystems.

- Scientific Monitoring and Research: Continuous monitoring of alpine species, climate parameters, and ecosystem health is vital for understanding trends, predicting future impacts, and informing conservation strategies. Research into climate-resilient species and restoration techniques is also critical.

- Empowering Local Communities: Engaging mountain communities, including indigenous peoples, in conservation initiatives is paramount. Their traditional ecological knowledge, stewardship, and active participation are essential for long-term success. Providing sustainable economic alternatives that reduce pressure on natural resources can also foster conservation.

- Public Awareness and Education: Raising global awareness about the beauty, importance, and fragility of alpine ecosystems can foster a sense of responsibility and mobilize support for conservation efforts.

Conclusion

The Alpine Ecosystems Crisis, driven by the relentless pressures of climate change and pervasive habitat loss, represents one of the most pressing environmental challenges of our time. From the unique flora and fauna of alpine biomes to the vital freshwater resources provided by mountain ecosystems, the stakes are incredibly high. These “water towers of the world” are signaling a profound imbalance, and their fate is inextricably linked to our own.

While the scale of the crisis can feel overwhelming, understanding the interconnected threats empowers us to act. By committing to ambitious global efforts to mitigate climate change, implementing sustainable land management practices that halt habitat loss, and empowering local communities, we can still secure a future where these majestic alpine ecosystems continue to thrive. The responsibility is collective, and the time to act is now, to safeguard these irreplaceable natural treasures for generations to come.

FAQ Section

What exactly is an alpine biome?

An alpine biome is a major ecological zone found above the treeline in mountain ranges worldwide. It is characterized by extreme cold, strong winds, intense UV radiation, short growing seasons, and poor, rocky soils. Despite these harsh conditions, it supports unique, specially adapted plants (like cushion plants and wildflowers) and animals (such as marmots, ibex, and pikas) that have evolved unique strategies to survive its challenging environment.

How do alpine ecosystems differ from other mountain ecosystems?

Alpine ecosystems are a specific type of mountain ecosystem defined by their position above the treeline. Other mountain ecosystems include montane and subalpine forests found at lower elevations. While all mountain ecosystems share general characteristics like varied topography and climate gradients, alpine zones are distinct for their treeless landscapes, more extreme weather conditions, and highly specialized, low-growing vegetation and cold-adapted wildlife.

What are some examples of species threatened by habitat loss in mountains?

Many species face habitat loss in mountain ecosystems. Examples include the snow leopard, whose habitat is threatened by human encroachment, livestock grazing, and infrastructure development across its Central Asian range. The Himalayan tahr, a large goat-antelope, faces pressure from habitat degradation and competition with domestic livestock. The American pika, an iconic alpine mammal, is highly susceptible to warming temperatures that shrink its cool, rocky habitat, and human development that fragments its populations.

How does climate change specifically impact glacial areas in alpine regions?

Climate change impacts glacial areas in alpine regions primarily through rapid warming, leading to accelerated glacial retreat and thinning. This results in reduced snowpack, earlier and faster meltwater runoff, and the complete disappearance of smaller glaciers. These changes disrupt seasonal water availability for ecosystems and downstream communities, increase the risk of landslides and rockfalls due to permafrost thaw, and contribute to sea-level rise.

What can individuals do to help protect mountain ecosystems?

Individuals can play a vital role in protecting mountain ecosystems by:

Are all alpine regions affected equally by these crises?

No, not all alpine regions are affected equally. While climate change is a global phenomenon, its impacts vary geographically due to local climatic conditions, topography, and the specific vulnerabilities of regional ecosystems. For instance, tropical glaciers in the Andes are retreating at a particularly alarming rate, while some temperate alpine regions might experience different sets of challenges. Similarly, the intensity and type of habitat loss threats vary depending on local human population density, economic activities, and conservation efforts.